Unlocking Knee Pain: How Cartilage Leftovers Fuel Joint Inflammation

Hey everyone! Let’s chat about something many of us know all too well: creaky, painful knees. If you’ve ever dealt with osteoarthritis (OA), you know that pain and stiffness are just the tip of the iceberg. One of the big troublemakers in early OA is something called synovitis – basically, inflammation of the joint lining. And guess what? It turns out that little bits of damaged cartilage might be adding fuel to that inflammatory fire.

The Joint’s Inner Workings and the Unexpected Guests

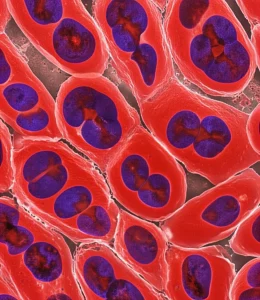

Picture this: inside your knee joint, you’ve got cartilage acting as a cushion, and a lining called the synovium. This lining is home to cells called fibroblast-like synoviocytes, or FLSs. Think of them as the joint’s housekeepers, normally keeping things smooth and happy.

Now, when that cartilage starts wearing down – which is the hallmark of OA – little bits and pieces break off. These aren’t just random debris; they’re essentially fragments from lysed (broken open) cartilage cells, called chondrocyte lysates (CLs). And these CLs, it seems, are not welcome guests in the joint space.

When Housekeepers Go Wild: The Inflammasome and Fiery Cell Death

So, what happens when these FLS housekeepers encounter the CLs? Well, the FLSs actually start to ‘eat’ or engulf these CLs. It’s a process called endocytosis. But instead of just cleaning up, this triggers something wild inside the FLSs called the NLRP3 inflammasome.

The NLRP3 inflammasome is like a tiny alarm system inside the cell. When it gets activated by things like these CLs, it kicks off a chain reaction. This reaction leads to something called pyroptosis. Don’t let the fancy name scare you; it literally means ‘fiery falling’. It’s a specific type of cell death that’s super inflammatory. When an FLS undergoes pyroptosis, it basically explodes, releasing all sorts of inflammatory signals (like IL-1β and IL-18) into the joint. This makes the synovitis way, way worse.

Think of it like this: the CLs are like little sparks, the FLSs engulf them, which ignites the NLRP3 inflammasome (the firestarter), leading to pyroptosis (the explosion), and the explosion releases inflammatory chemicals that make the joint lining angry and swollen (synovitis).

Enter Caveolin-1: The Doorman Who Gets Knocked Down

Okay, so how do the FLSs even grab onto these CLs in the first place? Well, there’s this protein on their surface called Caveolin-1, or CAV1. It’s kind of like a tiny doorman or a specific entry point on the cell membrane that helps regulate what gets taken inside (that endocytosis we talked about).

Here’s the kicker, and it’s a big part of what this study found: when the FLSs take in these CLs, the CLs actually *turn down* the volume on that CAV1 doorman. They suppress its expression. So, you end up with less CAV1 on the FLS surface.

And why is less CAV1 a problem? Because it seems CAV1 normally helps *keep a lid* on that NLRP3 inflammasome. When CAV1 levels drop, the NLRP3 alarm system becomes *more* easily triggered. So, the CLs come in, reduce CAV1, and this makes the FLSs hyper-reactive, leading to more NLRP3 activation and more pyroptosis.

Putting it to the Test: What Happens When You Boost CAV1?

The scientists didn’t stop there. They wanted to see if this CAV1 connection was really important in a living joint. They used a mouse model of OA (specifically, they destabilized the medial meniscus, or DMM, in the knee, which mimics OA). They found that in these OA mice, just like in human OA patients, the synovium showed signs of increased NLRP3 and decreased CAV1.

Then, they tried boosting CAV1 levels in the knee joint of these mice using a special delivery method (an adeno-associated virus, or AAV, carrying the CAV1 gene). And guess what? When they increased CAV1, the signs of synovitis – like the thickening of the synovial lining and inflammatory cell infiltration – were significantly reduced. This strongly suggests that boosting CAV1 could be a way to calm down the joint inflammation in OA.

Finding the Specific Troublemaker Within the Lysates

The CLs are a mix of stuff from broken chondrocytes. The researchers wondered if there was a *specific* protein within the CLs that was doing the main damage – the one that triggers the NLRP3 inflammasome and knocks down CAV1. They did some clever detective work using mass spectrometry and other techniques to analyze what was in the CLs and what was interacting with NLRP3 in the FLSs.

They identified a protein called LPP (LIM-containing lipoma preferred partner). And bingo! When they tested LPP on FLSs by itself, it did just what the whole CL mixture did: it significantly increased inflammatory signals, ramped up NLRP3 and pyroptosis, and importantly, it *downregulated* CAV1 expression. This points to LPP as a key player in this whole inflammatory cascade.

The Big Picture and What it Means

So, let’s wrap this up. This study paints a pretty clear picture of how damaged cartilage contributes to knee inflammation. Here’s the simplified story:

- Cartilage breaks down in OA, releasing Chondrocyte Lysates (CLs), which contain the protein LPP.

- FLSs in the joint lining take up these CLs (partially regulated by CAV1).

- The CLs (specifically LPP) then *reduce* the amount of CAV1 in the FLSs.

- Lower CAV1 levels make the NLRP3 inflammasome more active.

- Activated NLRP3 triggers pyroptosis – inflammatory cell death – in the FLSs.

- This pyroptosis releases inflammatory molecules, making knee synovitis worse.

It’s a vicious cycle where cartilage damage directly fuels the inflammation in the joint lining, making the OA symptoms worse. Understanding this specific pathway – involving CLs, LPP, CAV1, NLRP3, and pyroptosis – is super important because it gives us new ideas for how to intervene. Maybe we could target LPP, or find ways to keep CAV1 levels high in the FLSs, or block the NLRP3 inflammasome specifically in these cells. This research offers some exciting new potential therapeutic targets for tackling knee synovitis and hopefully slowing down the progression of OA.

Of course, science is always a journey, and there are always more questions to answer. The researchers note that getting normal human synovial tissue can be tricky, and more studies are needed, especially in living organisms, to fully understand all the nuances and potential side effects of targeting these pathways. For instance, CAV1 might have different roles in cartilage itself compared to the synovium, so any treatment would need to be very precise.

But hey, every step forward like this brings us closer to better ways to manage and treat conditions like OA that affect so many lives. It’s pretty fascinating how these tiny cellular interactions can have such a big impact on how our knees feel!

Source: Springer