Ouch! Kidney Stones, Nasty Oxidative Stress, and the Scoop on Papillary Calculi Types

Hey there! Ever found yourself wincing at the mere thought of kidney stones? I don’t blame you; they’re notorious little troublemakers. But have you ever wondered what’s really going on in there to make them form? Well, today I want to chat about a sneaky culprit called oxidative stress and how it plays a big role, especially when it comes to stones that form in a specific part of the kidney called the renal papilla. And trust me, not all these “papillary stones” are cut from the same cloth!

So, What’s Oxidative Stress Got to Do With It?

Alright, let’s break it down. Oxidative stress is basically when there’s an imbalance – too many reactive oxygen species (ROS), which are like tiny, energetic rascals, and not enough antioxidants to calm them down. These ROS can damage tissues, and when this happens in the kidney, particularly the renal papilla, it can set the stage for stone formation. But it’s not a one-size-fits-all scenario; there are a couple of main ways this can go down.

Imagine this first pathway: your urine might have pretty normal levels of the stuff that can form stones, like calcium oxalate. But, if ROS start causing lesions in your papillary tissue, your body’s immune system kicks into gear. This means an accumulation of macrophages (think of them as cellular cleanup crews) and inflammatory molecules. All this activity can produce cellular debris, and this debris can act like a tiny seed, or what we call a heterogeneous nucleant, for crystals to start growing. If the damage is inside the papillary tissue, which is bathed in interstitial fluid with a pH of around 7.4 (like your plasma), then apatite phosphate deposits can form. If your immune system doesn’t clear these out, they can grow, eventually break through the surface of the papilla, and once they hit the urine, boom! Calcium oxalate can start to grow on top of them. This initial apatite deposit is famously known as Randall’s plaque.

Now for the second pathway. This one happens when your urine has a high concentration of calcium (maybe you have hypercalciuria) and the urinary pH in the renal tubules is above 6.2. These conditions are perfect for crystals to form right inside those tiny tubules. When these crystals rub up against the tubule cells, they can cause damage. These calcium oxalate crystals can mess with cell membranes and even ramp up ROS levels by sticking to the cells, sometimes leading to cell death. Again, the immune system gets activated, bringing in inflammatory cells and molecules, which can ironically lead to even more calcium oxalate crystals. This can cause blockages in the renal tubules, creating plugs at the very tip of the papilla. When these plugs meet the urine, papillary stones can form. See? Different starting points, but both can lead to those painful stones.

It’s super important to figure out which pathway is at play because the underlying causes are different, and so are the best ways to prevent them!

Peeking into the Stone Collection: How We Figured This Out

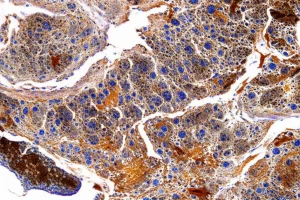

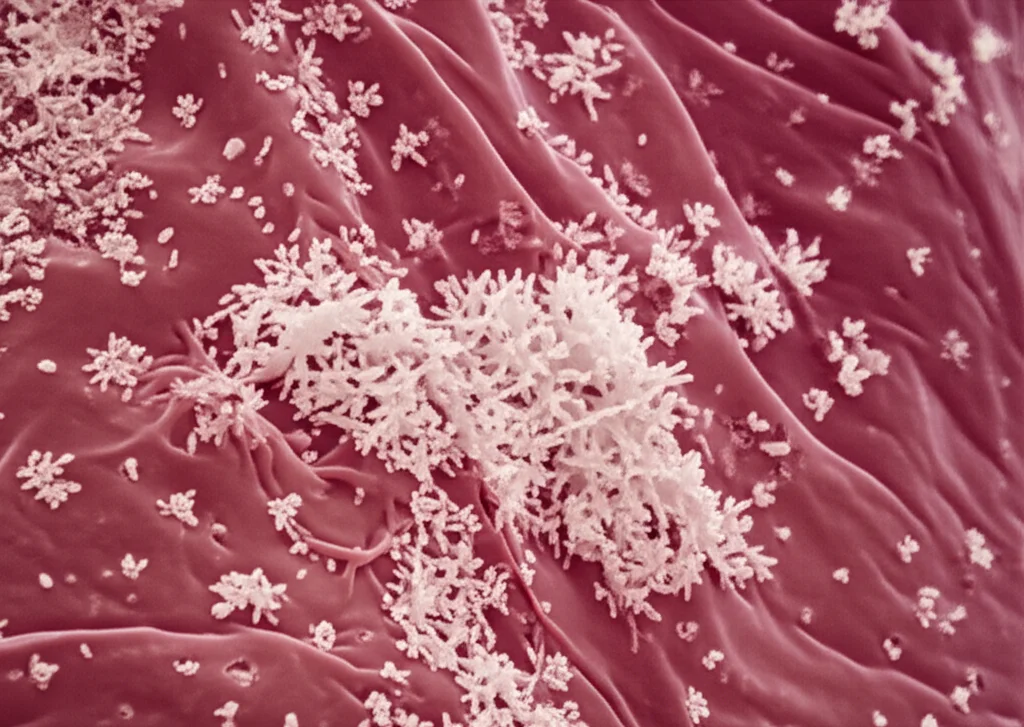

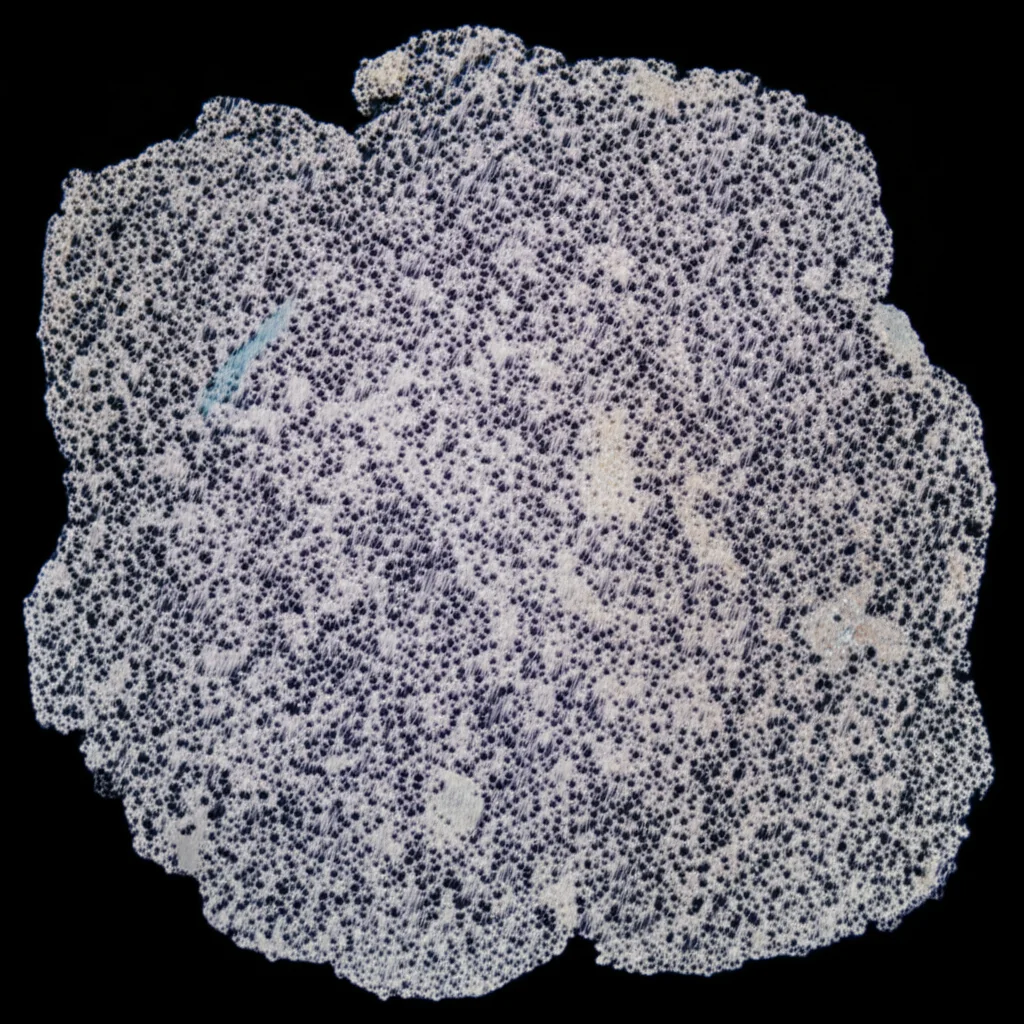

You might be wondering how we know all this. Well, scientists, including the brilliant minds behind the study I’m drawing from, have access to amazing resources like kidney stone biobanks. Imagine a library, but instead of books, it’s filled with thousands of kidney stones – in this case, a collection of 15,000! To understand these stones, they’re examined pretty meticulously. It starts with a good look under a stereoscopic microscope. If a stone looks like it came from the papilla, they zoom in on the surface to see if it’s made of calcium oxalate monohydrate (COM), calcium oxalate dihydrate (COD), or uric acid. They pay special attention to the area where the stone might have been attached to the papilla, looking for apatite phosphate, bits of renal tubules, or other crystal deposits. To get an even closer look and confirm what things are made of, they use powerful tools like scanning electron microscopy (SEM) coupled with energy dispersive X-ray microanalysis. This even lets them map out where different elements like calcium, phosphorus, and nitrogen are located within the stone. It’s like creating a detailed chemical map of each tiny culprit!

After this initial once-over, the stone is carefully cut in half, right through the area where it was attached to the papilla. This allows for a crystal-clear view (pun intended!) of any calcified renal tubules, where they are in relation to apatite deposits, how the apatite is linked to the stone’s development, and if there are any urates in the attachment zone. It’s some serious stone sleuthing!

The Five Faces of Papillary Kidney Stones

Through this kind of detailed investigation, we’ve been able to identify five distinct types of renal papillary calculi. Let me introduce you to the lineup:

-

Type I: The Classic Randall’s Plaque Stone (No Tubules in Sight)

These are COM (calcium oxalate monohydrate) papillary stones. What’s characteristic here is that Randall’s plaque – that apatite phosphate layer – is clearly there at the junction with the papilla, but you won’t find any renal tubules in that specific area. These stones are often small, with a smooth, convex growing surface and a concave side that was in contact with the kidney tissue. The formation of Randall’s plaque is a bit like how bones mineralize. It often involves cytotoxic substances causing ROS, which then oxidize collagen fibers in the papilla. These oxidized fibers become great spots for hydroxyapatite to start forming. This is more common in folks exposed to certain pesticides or solvents, or those taking particular drugs. Interstitial fluid is already supersaturated with calcium phosphates, so if there’s a lack of natural inhibitors (like pyrophosphate or citrate), these deposits can grow. Interestingly, not all these calcifications turn into stones; they need to actually reach the urine.

-

Type II: Randall’s Plaque with Tubule Trouble

Type II stones are also COM papillary calculi, and they too have Randall’s plaque at the stone-tissue junction. The big difference? You’ll also find calcified renal tubules (either blocked or open) and plugs in that same area. This scenario usually points to high urinary concentrations of calcium and/or oxalate. This supersaturation leads to crystals forming inside the renal tubules, which then damage the tubular lining, leading to plugs. When these damaged tubules and plugs reach the papilla’s tip and hit the urine, COM stones can develop, often incorporating these calcified tubules.

-

Type III: The COD Stone with Tubule Drama

Now we meet the COD (calcium oxalate dihydrate) stones. For Type III, the junction where the stone met the papilla is clearly visible, and just like Type II, there are calcified renal tubules and plugs present. The underlying cause is similar to Type II – high urinary calcium and/or oxalate leading to crystal formation and damage within the tubules. These COD stones can be a bit tricky to identify as papillary because their shape is often irregular, and the attachment area can be missed. They might consist mostly of COD crystals with small bits of hydroxyapatite and fragments of calcified tubules at the junction.

-

Type IV: The Uric Acid Mix-Up

Type IV stones are primarily COM papillary stones, but they come with a significant layer of uric acid crystals, or sometimes sodium or potassium urates. It seems the COM part, the initial papillary stone, forms first. Then, if the urine pH drops below 5.5 (making it acidic), uric acid can crystallize on top of the COM. COM crystals are actually pretty good at encouraging uric acid crystals to form! Sometimes, you might see needle-like sodium urate crystals around the stone-papilla junction, occasionally even alongside Randall’s plaque. This suggests that after the Randall’s plaque formed, urine with a high pH and too much uric acid (hyperuricosuria) led to the urate formation. What’s really curious is that sometimes bacterial imprints are found in the hydroxyapatite deposits in this area. This could mean the initial damage to the papilla’s surface wasn’t from within but perhaps due to a bacterial infection.

-

Type V: The Mystery COM Stone (No Plaque Here!)

Finally, we have Type V stones. These are small COM papillary calculi, but here’s the puzzle: there are no hydroxyapatite or apatite phosphate deposits (no Randall’s plaque) at the stone-tissue junction. The COM crystals, often in a columnar structure, seem to form directly on the papillary tissue or some organic matter there. Explaining how these form is a bit tougher. The complete absence of those typical hydroxyapatite residues might mean the stone started directly on a small patch of damaged epithelium on the papilla’s surface. Perhaps a subepithelial deposit of something else, or another factor, directly messed with the cells covering the papilla.

So, What’s the Big Picture on Papillary Stones?

As you can see, renal papillary stones aren’t a monolith. They can form through several different pathways. However, a common thread seems to be some kind of tissue lesion or damage. This damage can be sparked by oxidative stress from cytotoxic agents, by having urine that’s overloaded with calcium and/or oxalate, or by some other insult that harms the delicate cuboidal epithelium covering the papilla.

The good news? Our bodies have defense mechanisms! A competent immune system can play a crucial role in preventing these stones from developing in the first place. It can help by eliminating those early intratissue hydroxyapatite deposits or by promoting the regeneration and healing of the outer epithelium of the papilla. So, while these stones are a pain, understanding how they form is the first step towards better prevention and treatment. It’s a complex dance of chemistry, biology, and sometimes, just bad luck, but science is always working to unravel the steps!

Source: Springer