Unraveling the Wobbly Bits: How CYP1B1’s “Spaghetti” Regions Could Unlock Secrets of Childhood Glaucoma

Hey there! Ever wondered how the tiniest changes at a molecular level can lead to big health problems? Well, we’ve been diving deep into something just like that, focusing on a severe eye disorder called primary congenital glaucoma (PCG). It’s a tough one, potentially leading to blindness in kids if not caught and treated early. Our spotlight is on a protein called Cytochrome P450 1B1 (CYP1B1), which plays a super critical role in PCG.

Now, here’s where it gets really interesting. We’re looking at something called “intrinsically disordered proteins and regions” – or IDPs/IDPRs for short. Think of them as the flexible, “spaghetti-like” parts of proteins that don’t have a fixed, rigid structure. These floppy bits are turning out to be major players in diseases because their flexibility affects how proteins chat with each other and do their jobs. So, our big question was: what’s the deal with intrinsic disorder in CYP1B1, and how does it tie into PCG?

To get to the bottom of this, we rolled up our sleeves and used a bunch of cool bioinformatics tools. One of them, AlphaMissense, is pretty nifty – it helps predict how damaging tiny changes (missense mutations) in a protein might be. Our structural peek showed that, yep, CYP1B1 has these unstructured, flexible IDPRs. And here’s a kicker: we found that the more disordered a region is, the less likely mutations there are to be harmful. It’s like these floppy bits can soak up some of the damage! This finding could help explain why PCG shows up so differently in various patients, even with similar CYP1B1 mutations. We’re hoping these insights will not only boost our understanding of PCG at a molecular level but also point us towards new ways to fight this blinding childhood disease. Stick with me, and I’ll walk you through what we found!

So, What Exactly is Primary Congenital Glaucoma (PCG)?

Primary congenital glaucoma, or PCG, is a bit of a tough genetic condition. It causes problems in the eye’s drainage system – specifically, the trabecular meshwork and anterior chamber angle. When these don’t develop right, the pressure inside the eye (intraocular pressure, or IOP) can shoot up. It’s not super common, but its prevalence varies – from about 1 in 1,250 in a specific group in Slovakia to 1 in 20,000 in Western countries. It can pop up sporadically or run in families, with about 10-40% of cases being familial and inherited in an autosomal recessive way.

PCG is categorized by when it starts:

- Neonatal onset: 0–1 month old

- Infantile onset: >1–24 months old

- Late onset: >24 months old

The official definition, according to the Childhood Glaucoma Research Network, is glaucoma that develops without other acquired or nonacquired conditions, often with buphthalmos (that’s an enlarged eyeball). Besides buphthalmos, little ones with PCG might show signs like excessive tearing (epiphora), sensitivity to light (photophobia), eyelid spasms (blepharospasm), frequent eye rubbing, and general irritability. When doctors take a look, they might find high IOP, a cloudy or swollen cornea, an increased corneal diameter, breaks in a corneal layer called Descemet’s membrane (these are called Haab striae), and a longer eyeball. Sometimes, the iris might look like it’s inserting too far forward into the trabecular meshwork. All these developmental hiccups can block the eye’s fluid from draining properly, jacking up the IOP and eventually damaging the optic nerve, leading to early vision loss. It’s pretty serious stuff.

The Genetic Culprit: Meet CYP1B1

Thanks to cool tech like exome sequencing, we’ve gotten much better at finding genes linked to PCG. The main gene in the spotlight is Cytochrome P450 1B1 (CYP1B1). It’s found on chromosome 2 (at locus GLC3A, 2p21, to be exact). CYP1B1 is part of a big family of enzymes, the cytochrome P450s, and it’s involved in metabolizing stuff crucial for development, like steroids and retinoids. The theory is that when CYP1B1 has variants (mutations) in PCG, it messes up how retinol (a form of Vitamin A) is processed. This, in turn, disrupts the levels of retinoic acid, which is vital for proper eye development.

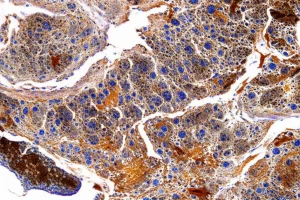

Studies also tell us that CYP1B1 is a key player in managing oxidative stress and keeping the trabecular meshwork and retinal tissues healthy. If its expression gets messed up, it can lead to more oxidative stress, weird changes in the extracellular matrix, and generally unhappy cells in these eye tissues.

Loads of different mutations in CYP1B1 have been found to cause PCG, and some are “founder mutations” – meaning they’re common in specific populations. For example:

- p.Gly61Glu in Iran, Lebanon, and Saudi Arabia

- p.Arg390His in Pakistan

- p. 4,339delG in Morocco

- p.Glu387Lys in Europe

- p.Val320Leu in Vietnam and South Korea

Other mutations include things like a c.107G>A missense mutation and even deletions. Generally, CYP1B1 mutations are linked to more severe PCG – think higher eye pressure and needing more surgeries. While other genes like CDT6/ANGPTL7 and LTBP2 are also implicated, CYP1B1 is the big one. It’s likely that multiple genes contribute to PCG, though, because we see things like incomplete penetrance (not everyone with the mutation gets the disease) and variable expressivity (people get it to different degrees).

The most accepted idea is that these genetic changes mess up the downstream pathways that CYP1B1 controls, leading to those abnormal eye structures and glaucomatous changes. Specifically, CYP1B1 mutations seem to stop embryonic neural crest cells (which are supposed to become the trabecular meshwork) from migrating correctly. This leads to the goniodysgenesis – or malformation of the eye’s drainage angle – that we see in PCG.

Why We’re Fascinated by “Wobbly” Proteins

Our research group is super interested in how these genetic mutations actually change the protein’s function, especially at the level of its local structure. This brings us to those intrinsically disordered proteins (IDPs) and intrinsically disordered protein regions (IDPRs) I mentioned earlier. These guys are everywhere in living things! They’re functional proteins or parts of proteins that don’t have a stable, fixed 3D shape. Instead, they’re highly flexible, like molecular spaghetti, and can have multiple functional segments. Understanding how mutations affect these disordered regions can give us huge clues about disease mechanisms and even new ways to treat them.

So, our study set out to understand PCG through this lens of protein intrinsic disorder. We wanted to:

- Figure out how much of CYP1B1 is made up of these IDPRs.

- See what these disordered regions are capable of doing compared to the more structured parts.

- Map out CYP1B1’s network of protein buddies (its protein-protein interactions, or PPIs).

Our hunch was that CYP1B1 has a fair bit of this intrinsic “wobbliness” and that the genetic mutations linked to PCG mess with how these regions behave, ultimately leading to the disease. If mutations in CYP1B1 change these disordered bits, especially depending on whether the mutation is in an ordered or disordered part, these features could become targets for future PCG therapies. Ultimately, we want to shed more light on the molecular nitty-gritty of PCG.

Our Digital Toolkit: How We Probed CYP1B1

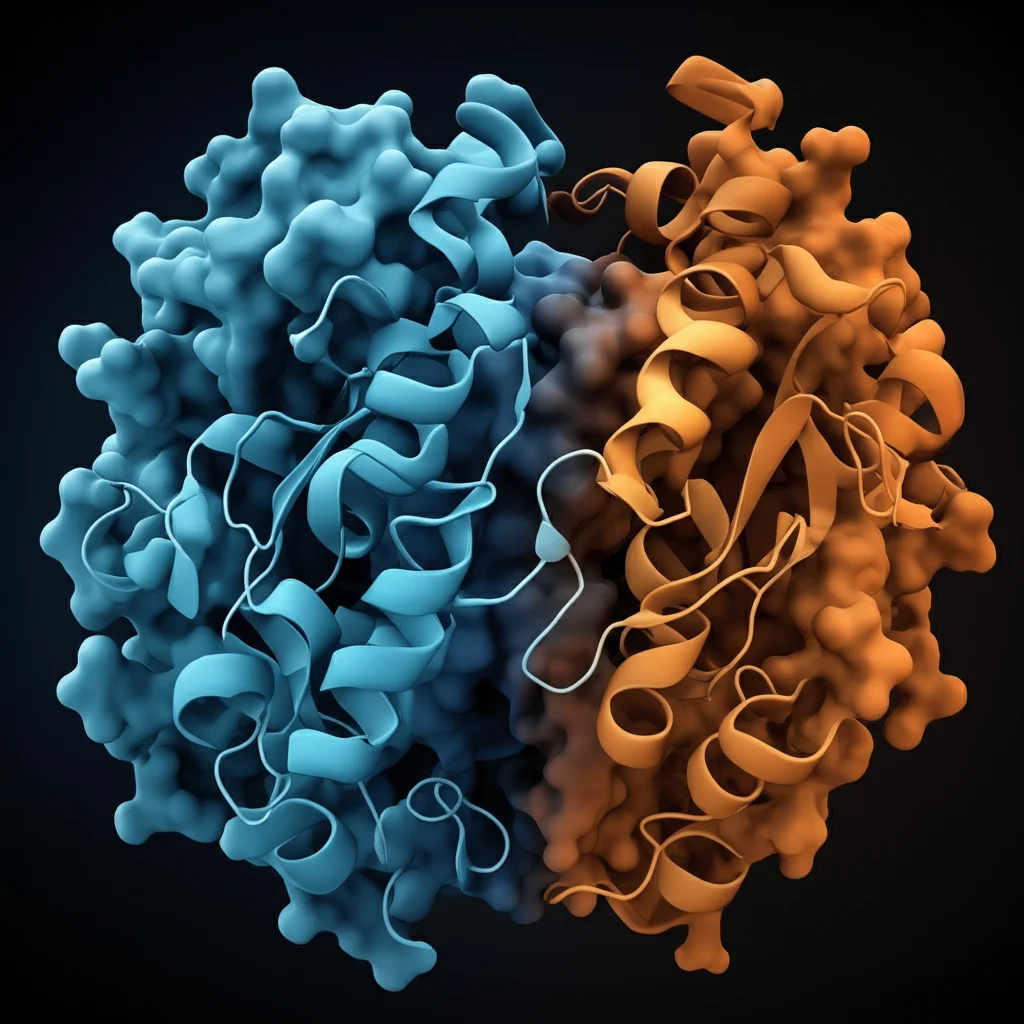

To get these answers, we dived into a comprehensive structural bioinformatics analysis. Think of it as using powerful computers and smart algorithms to study the protein in detail. We grabbed the standard amino acid sequence of human CYP1B1 from UniProt (the Q16678 entry, if you’re curious). Then, we got its 3D structure prediction from the AlphaFold Protein Structure Database. AlphaFold, developed by Google’s DeepMind, is amazing at predicting protein structures with high accuracy.

Building on that, DeepMind also created AlphaMissense, a tool that predicts the functional impact of missense mutations (those single amino acid changes). Since missense mutations are super common in CYP1B1, we used AlphaMissense to score their potential pathogenicity from 0 (likely benign) to 1 (likely pathogenic). We stuck to their cutoffs: scores between 0.34 and 0.564 are “ambiguous.” We even color-coded the AlphaFold structure of CYP1B1 based on these average pathogenicity scores for each residue – blue for benign, red for pathogenic, and white for ambiguous. This gave us a cool visual of which parts of the protein are mutational hotspots.

We also used the Composition Profiler to see if CYP1B1 has more or less of certain amino acids compared to highly structured proteins (from PDB Select 25) or known disordered proteins (from DisProt). To quantify the intrinsic disorder, we used a suite of six well-known predictors (PONDR®VLXT, VL3, VLS2, FIT, and IUPred2 Short e Long) via a tool called RIDAO (Rapid Intrinsic Disorder Analysis Online). This gave us a disorder score for each residue; anything 0.5 or above is considered disordered. From this, we calculated the percentage of predicted disordered residues (PPDR).

Then came the correlation crunch! We looked at how the mean disorder profile (MDP – an average of all those disorder predictions) related to the AlphaMissense average pathogenicity scores. We plotted them, smoothed out the data, and even fitted an exponential decay curve to see the trend. To get more functional info, we turned to FuzDrop, which tells us if a protein is likely to undergo liquid-liquid phase separation (LLPS – think of proteins forming little droplets in the cell), where aggregation hot spots might be (regions that could make the protein clump up), and which regions might have context-dependent binding. Finally, we used the D2P2 database to look at disorder-related functions and the STRING database to map out CYP1B1’s protein-protein interaction network. Phew! That’s a lot of digital detective work.

What We Found: CYP1B1’s Wobbly Nature

Okay, so what did all this digging reveal? First off, the human CYP1B1 protein is pretty big, with 543 amino acids. The AlphaFold2 model showed it has a highly structured core but also these “spaghetti-like” disordered bits on the periphery. Specifically, we saw flexible, unstructured regions around residues 0-60, 140-180, 210-240, 280-320, and 520-543. The very ends of the protein (N- and C-termini) also looked pretty disordered.

When we overlaid the AlphaMissense pathogenicity scores, a cool pattern emerged: those disordered, low-confidence areas in the AlphaFold structure tended to have more benign (less harmful) mutations. The average pathogenicity score for CYP1B1 was 0.51. This isn’t saying these mutations will happen, just how likely they are to mess things up if they do.

The Amino Acid Mix and Disorder Levels

Looking at its amino acid makeup, CYP1B1 was significantly enriched in some order-promoting residues (like F, L, H, V, M) and some disorder-promoting ones (R, A, Q, S, P). It was also depleted in others. This mix hints at its complex structural nature.

As for how disordered it is overall, the predictors gave slightly different answers. PONDR®VLXT (15.65% disordered) and VSL2 (17.86%) called it “moderately disordered.” But PONDR®VL3 (8.47%), FIT (8.29%), IUPred-Long (1.10%), and IUPred-Short (2.39%) suggested it was “highly ordered.” So, it’s a bit of a mixed bag, but definitely has disordered character.

The Big Link: Disorder and Pathogenicity

This was a key part of our study. When we plotted the smoothed average pathogenicity scores against the mean disorder profile (MDP), we saw a clear trend: an exponential decay fit with an R2 value of 0.62. In plain English, this means that as disorder increases, the predicted pathogenicity of mutations tends to decrease exponentially. So, the most “wobbly” regions are more likely to tolerate mutations without causing a catastrophe. Looking at it residue by residue, peaks of high disorder lined up nicely with areas of low pathogenicity, and structured regions often corresponded to higher pathogenicity scores. This suggests these flexible regions might act as buffers against harmful mutations!

Droplets, Clumps, and Adaptable Binding

The FuzDrop platform gave us more cool insights. CYP1B1 itself has a low tendency to form those protein droplets (LLPS) on its own (pLLPS score of 0.3692), making it a ‘droplet client’ – it needs partners. But it has three droplet-promoting regions (DPRs at residues 1-14, 295-322, and 367-377), and these overlap with its disordered regions. FuzDrop also flagged four “aggregation hot spots” (residues 8-14, 47-52, 299-307, 314-322) – bits that could make the protein sticky and prone to clumping. Plus, CYP1B1 has 20 “context-dependent” regions, meaning they can switch their binding modes, and these also hang out near or within the disordered regions. This all points to a very dynamic and adaptable protein.

Functional Domains and a Busy Social Life

The D2P2 database confirmed the disorder predictions and showed that CYP1B1 has one main functional domain, the “Cytochrome P450” domain (residues 51-523). Interestingly, we didn’t find any predicted molecular recognition features (MoRFs – short binding sites in disordered regions) or post-translational modifications (PTMs) in the sequence. The most disordered bits are near the N-terminus and overlap with this functional P450 domain, hinting at a link between disorder and function.

Finally, the STRING analysis revealed that CYP1B1 is quite the social butterfly! It has a dense network of interacting partners – 56 nodes (proteins) and 268 edges (interactions), way more than expected by chance. This high connectivity (average node degree of 9.57 and a high clustering coefficient of 0.892) tells us it’s part of a tight-knit protein cluster and plays a significant role in many cellular pathways. Messing with it through mutations could clearly have widespread effects, especially in eye development.

What Does This All Mean for PCG?

So, we’re the first, as far as we know, to really look at these intrinsically disordered regions (IDPRs) in the context of glaucoma, specifically PCG. Our bioinformatics deep dive painted a picture of CYP1B1 as a protein with a structured core but also important flexible, disordered regions. The big takeaway is that mutations in highly disordered regions seem to be less damaging. This was backed up by that R2 value of 0.62 showing disorder decreasing as predicted pathogenicity increases – a trend also seen across the whole human proteome in the original AlphaMissense study.

Let’s look at some known PCG-causing mutations:

- The common p.Gly61Glu mutation (found in Iran, Portugal, Saudi Arabia, Brazil, Vietnam) occurs at residue 61, which our RIDAO analysis puts in an ordered region. Glycine is disorder-promoting, and glutamate is even more so. Changing from one disorder-promoter to an even stronger one in an ordered region could definitely cause trouble. AlphaMissense agrees, giving it a whopping pathogenicity score of 0.9839 (highly pathogenic!). This fits our finding that mutations in ordered regions are more likely to be nasty.

- The European founder mutation p.Glu387Lys is also in an extremely ordered region. Again, it’s a change from a disorder-promoting residue (Glu) to the most disorder-promoting residue (Lys). AlphaMissense score? 0.9508 – very pathogenic.

- Pakistan’s founder mutation, p.Arg390His, is in the same highly ordered spot. Here, a disorder-promoting residue (Arg) changes to an order-promoting one (His). This might seem counterintuitive, but any change in such a critical ordered spot could be bad news. AlphaMissense gives it 0.8207 (pathogenic), a bit lower than the others, suggesting that mutations favoring disorder in ordered regions might be the worst, followed by those favoring order in ordered regions.

- The p.Val320Leu mutation (Vietnam, South Korea) is different. It’s in a more disordered part of the protein, and it’s a change from an order-promoting residue (Val) to an even more order-promoting one (Leu). While our general finding is that disordered regions are less sensitive, this suggests that forcing order into a normally flexible spot could also be problematic. However, AlphaMissense rated this one as “ambiguous” (0.381), reinforcing that mutations in ordered regions are generally more concerning.

Of course, we focused on missense mutations, but other types, like frameshift mutations, can also wreak havoc by drastically shortening the protein. And while AlphaMissense is a powerful predictor, it’s not the final word. Our study is bioinformatics-based, so more lab work and clinical research are needed to nail down exactly how these IDPRs contribute to PCG.

Peeking into the Future: Can We Target These Wobbly Bits?

Thinking ahead, gene therapy is an exciting avenue for PCG. While current treatments are mainly surgery and meds to lower eye pressure, understanding CYP1B1’s structure, especially its wobbly bits, could open doors for targeted gene therapies. Could we design treatments to stabilize these disordered regions if they’re involved in misfolding or dysfunction? It’s an intriguing thought!

Our study used AlphaFold2, which was great for visualizing. Future work could use AlphaFold3 (once it’s fully out of beta) to get even deeper insights into how the protein moves and interacts with DNA, RNA, and other proteins. We could also bring in newer, high-performance disorder predictors to make our analysis even more robust.

The Takeaway Message

In a nutshell, our research shows that the CYP1B1 protein is a fascinating mix of stable, ordered structures and flexible, disordered regions. These “wobbly bits” aren’t just random; they seem to give the protein functional flexibility, allowing it to interact with many partners and do its various jobs. This complex structure also helps explain its broad interaction network. More importantly for PCG, understanding this interplay between order and disorder, and how mutations affect it, could give us brand-new targets for therapies. By figuring out the secrets of CYP1B1’s wobbly regions, we might just find better ways to tackle this challenging childhood eye disease. How cool is that?

Source: Springer