Unpacking ILD in India: What Really Matters for Health Status?

Understanding ILD and the Indian Context

Hey there! Let’s talk about something pretty important: Interstitial Lung Disease, or ILD. It’s not just one thing, you know? It’s an umbrella term for a whole bunch of conditions that make the tissue in your lungs get all scarred and stiff. Imagine trying to breathe through a sponge that’s hardening up – that’s kind of what we’re talking about. People dealing with ILD often feel breathless, tired, and find it tough to do everyday things. It can really knock your quality of life down.

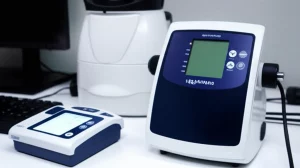

Now, the way ILD progresses can be really different from person to person. Sometimes it’s slow and steady, sometimes it speeds up, and sadly, the outlook often isn’t great, even with newer treatments. Diagnosing and keeping tabs on it usually involves things like fancy scans (HRCT) and lung function tests (PFTs).

Here’s where it gets interesting, especially when we look at places like India. Environmental stuff, cultural vibes, even genetics can play a role in how the disease shows up and moves along. And let’s be real, access to all those high-tech tests isn’t always a given everywhere. Sometimes, diagnosis gets delayed because the tools aren’t there, or maybe people are hesitant, or other things get blamed first.

Because of these unique factors – the environment (like biomass smoke, which is a big deal there), the potential for delayed diagnosis, and maybe even cultural expectations around illness – the relationship between how severe the disease looks on paper and how it *actually* impacts someone’s health status might be a bit different compared to what we see in higher-income countries. And honestly, we haven’t really looked into that much before in a place like India. That’s exactly what this study aimed to figure out.

Peeking Behind the Curtain: How They Studied It

So, what did they do? They ran an observational study at one hospital in India. They brought in 80 participants who had already been diagnosed with ILD. These folks did a bunch of tests between 2020 and 2022.

They checked their lung function using PFTs, specifically looking at:

- Forced Vital Capacity (FVC) % predicted: Basically, how much air you can blow out forcefully after taking a deep breath, compared to what’s expected for someone your age, size, etc.

- Diffusing Capacity of the Lung for Carbon Monoxide (DLCO) % predicted: This one is key. It measures how well oxygen (or in this test, a tiny bit of carbon monoxide) passes from the air sacs in your lungs into your bloodstream. It’s a really sensitive way to check gas exchange efficiency.

They also measured things that tell us about a person’s health status in real life:

- 6-Minute Walk Distance (6MWD): How far they could walk in six minutes. A simple, practical test of exercise capacity.

- St. George’s Respiratory Questionnaire (SGRQ): A questionnaire that asks about symptoms, activities, and the impact of the disease on their daily life. A higher score means worse health-related quality of life (HRQoL).

- modified Medical Research Council (mMRC) dyspnoea scale: A simple scale (0-4) to rate how breathless they feel during different levels of activity.

They wanted to see if there were connections (correlations) between the lung function numbers (DLCO, FVC) and the real-world measures (6MWD, SGRQ). They also peeked at how things looked based on how long someone had been diagnosed, whether they were male or female, and how breathless they felt.

What the Numbers Told Us: Surprising Connections

Okay, here’s the juicy part. When they crunched the numbers, they found some pretty strong links. Get this:

There was a strong correlation between DLCO % predicted and the 6MWD. Think of it this way: the better your gas exchange (higher DLCO), the further you could walk in six minutes. Makes sense, right? If your lungs are better at getting oxygen into your blood, your muscles get the fuel they need to walk further.

They also found a strong correlation between DLCO % predicted and the SGRQ Total score. This means that when gas exchange was worse (lower DLCO), people reported a significantly worse quality of life. Again, totally intuitive – if you can’t breathe well, everything is harder, and life quality suffers.

But here’s the kicker, and it’s a finding that aligns with some previous research but goes against what some might assume: there was no significant correlation between FVC % predicted and *either* the 6MWD or the SGRQ Total score. Yep, that measure of how much air you can blow out didn’t seem to strongly predict how far someone could walk or how they felt about their quality of life in this group.

They also saw some interesting differences based on other factors. For instance, males tended to have higher DLCO but slightly lower FVC compared to females. And folks with more severe breathlessness (higher mMRC scores) generally had lower DLCO and FVC values, which isn’t surprising – feeling more breathless usually means your lungs aren’t working as well.

The study also looked at how these measures lined up with standard ways of grading severity. They found that individuals walking less than 300 meters in the 6MWT (often considered severe impairment) were more likely to have moderate to severe impairment based on their DLCO values. Similarly, higher SGRQ scores (indicating worse quality of life) were strongly linked to lower DLCO values.

Why This Matters, Especially in India

So, why are these findings important? They really highlight a few key things:

First, in this specific population in India, DLCO seems to be a much better indicator of how ILD is truly impacting a person’s functional capacity (how much they can do physically) and their quality of life than FVC. While FVC is a standard measure and important for tracking disease progression over time, this study suggests it might not capture the *current* impact on daily life and exercise tolerance as well as DLCO does.

Second, and this is crucial for settings with limited resources, the study hints that even if advanced tests like DLCO aren’t readily available, more accessible tools can still provide valuable insights. The 6MWT and the SGRQ questionnaire, which are much simpler and less expensive to perform than a full PFT with DLCO, showed strong correlations with DLCO. This suggests that where DLCO testing is scarce, these accessible tests *can* give clinicians a good indication of disease severity and its impact on patients’ lives. This is a big deal for improving diagnosis and management, especially considering that delayed diagnosis is a known issue for ILD in India, contributing to poorer outcomes.

The study also touches on the unique factors in India, like environmental exposures (biomass fuel smoke being mentioned as a significant risk factor alongside tobacco), which might influence disease patterns and symptoms differently than in other regions. Cultural factors and patient priorities (sometimes focusing more on symptom relief than getting a precise diagnosis due to cost/access) can also shape the patient experience and how perceived severity aligns with objective measures.

Essentially, this research helps bridge the gap between clinical measures of lung function and the lived experience of people with ILD in India. It reinforces that quality of life and functional capacity are multi-faceted and not always perfectly reflected by a single lung function number like FVC.

A Quick Look at the Fine Print (Study Limitations)

Of course, like any study, this one had its limits. It was done at just one hospital, which means the findings might not perfectly apply to everyone with ILD across all of India. And 80 participants isn’t a massive crowd, so while the results are compelling, larger studies, maybe across different centers, would help confirm these relationships more broadly.

Also, this study primarily included participants with mild to moderate disease based on their DLCO values. The relationships might look different in people with very severe ILD. Future research could definitely explore these links in larger, more diverse groups and follow people over time to see how these measures predict things like disease progression and survival.

Bringing It All Together

So, what’s the big takeaway from this pioneering study in India? It gives us a clearer picture: while FVC is a standard measure, DLCO % predicted seems to be a more robust indicator of the *impact* of ILD on functional exercise capacity and health-related quality of life in this population. This aligns with the understanding that DLCO is particularly sensitive to the gas exchange problems central to ILD.

Crucially, the study highlights the potential value of more accessible tools like the 6-minute walk test and the SGRQ questionnaire. In settings where DLCO testing is limited – a reality in many parts of India – these tests can provide valuable, practical insights into how severe the disease is and how much it’s affecting patients’ daily lives. This is vital information for guiding care and prioritizing interventions, especially those focused on symptom relief and improving functional capacity.

Understanding these relationships better helps clinicians and physiotherapists tailor their approach, focusing on what truly matters to patients: being able to breathe better, move more easily, and have a better quality of life. It’s a step towards ensuring that even with diagnostic challenges, people with ILD in India can receive care that addresses the real-world impact of their disease.

Source: Springer