Hopping into the Magnetic World of Spinel Ferrites: A Doping Adventure

Hey there, fellow science curious folks! Let’s dive into something really cool today – tiny magnetic materials called spinel ferrites. You know, those crystalline structures that are super useful in all sorts of tech, from your phone to medical devices? Well, we’ve been playing around with a specific type, a mix of Cobalt and Nickel ferrites, and we decided to spice things up by adding a touch of a rare earth element called Holmium (Ho). Think of it like adding a secret ingredient to a recipe to see how it changes the final dish!

Why Spinel Ferrites?

First off, what’s the big deal with spinel ferrites? They have this neat cubic structure, kind of like a tiny, intricate building block, with the general formula MFe₂O₄, where ‘M’ is usually a metal like Nickel or Cobalt. What makes them special is their fantastic blend of magnetic and electrical properties. We’re talking high magnetization (they can get *really* magnetic), low electrical conductivity (which is great for minimizing energy loss), and a bunch of other useful traits like high Curie temperature (they stay magnetic even when it gets hot) and good mechanical hardness.

Because of these properties, they pop up everywhere:

- Microwave absorbers (so your signals don’t go wild)

- Magnetic storage (like in hard drives, though that’s evolving!)

- Sensors (detecting all sorts of things)

- Biomedical uses (like targeted drug delivery or hyperthermia for cancer therapy)

- Electronic devices and telecommunications

Among the spinel ferrite family, Nickel-Cobalt (Ni-Co) ferrites are particularly interesting. They’re ferrimagnetic (a type of magnetism where the magnetic moments don’t all align perfectly but still result in a net magnetic field) and boast high magnetostriction (they change shape slightly in a magnetic field), high anisotropy (they prefer to be magnetized in certain directions), and high permeability (they let magnetic fields pass through easily). This makes them fantastic for high-frequency applications and shrinking down devices.

Adding a Touch of Rare Earth: Why Holmium?

Now, here’s where our little adventure comes in. The properties of these materials are heavily influenced by how the different metal atoms are arranged within that spinel structure – what we call “cation distribution.” One way to mess with this arrangement and tweak the properties is by substituting some of the original atoms with others. Rare earth ions, like our friend Holmium (Ho³⁺), are particularly good at this because they have larger ionic radii and unique electron configurations that can really shake things up.

Holmium (Ho³⁺) is especially intriguing because it has one of the highest magnetic moments among the rare earths. Replacing some of the smaller Iron (Fe³⁺) ions with larger Ho³⁺ ions can significantly alter the structure and, consequently, the magnetic and electrical behaviors. Previous studies hinted at the potential of rare earth doping, but we wanted to take a closer look at how Ho³⁺ specifically impacts Ni-Co ferrites.

So, our goal was clear: synthesize Ni-Co spinel ferrites doped with varying amounts of Ho³⁺ and then put them under the microscope (literally and figuratively!) to understand their structure, magnetism, microwave behavior, and even the tiny interactions happening at the atomic level.

Whipping Up and Examining Our Nano-Ferrites

To make our Ho-doped Ni-Co spinel ferrites (which we affectionately call Ho→NiCoFe NSFs – NSFs for Nano Spinel Ferrites), we used a technique called hydrothermal synthesis. It’s basically like cooking them in a high-pressure, high-temperature water bath. We mixed up the right ingredients (metal salts) in water, adjusted the acidity, popped it all into a special container (a Teflon-lined autoclave), and heated it up. No extra baking needed afterward!

Once they were cooked, we had these tiny solid samples. To figure out what we made and how it looked, we employed a whole suite of fancy scientific tools:

- X-ray Diffractometry (XRD): To check the crystal structure and size.

- Scanning/Transmission Electron Microscopies (SEM/TEM): To see the shape and size of the particles.

- High Resolution TEM (HR-TEM): For super close-up views of the crystal lattice.

- Energy X-ray Spectrophotometer (EDX): To confirm the elements present.

- Vibrating Sample Magnetometer (VSM): To measure their magnetic properties at different temperatures.

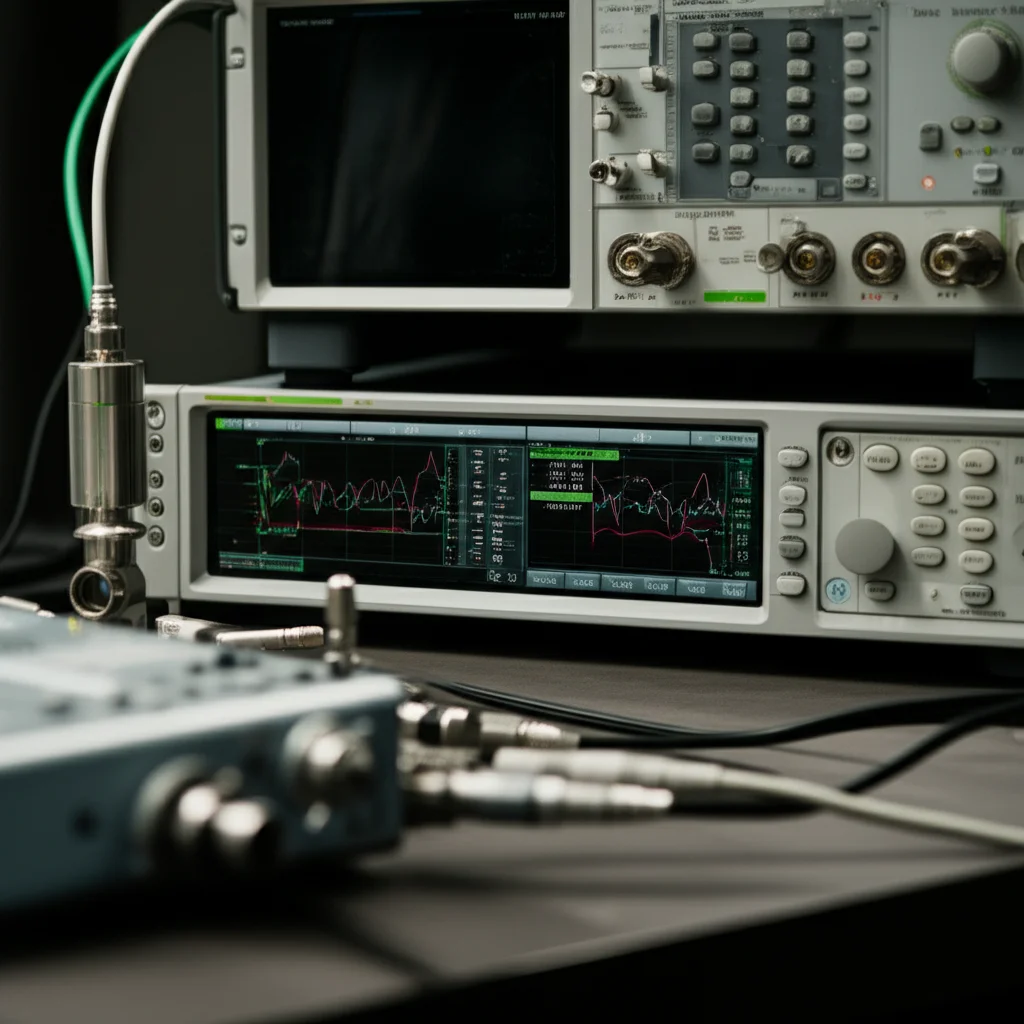

- Microwave Absorption Analyzer: To see how they interact with microwaves.

- Mössbauer Spectroscopy: To probe the local environment and magnetic interactions around the Iron atoms.

It’s like being a detective, using different tools to piece together the full story of these tiny materials!

The Structural Scoop: Where Did the Holmium Go?

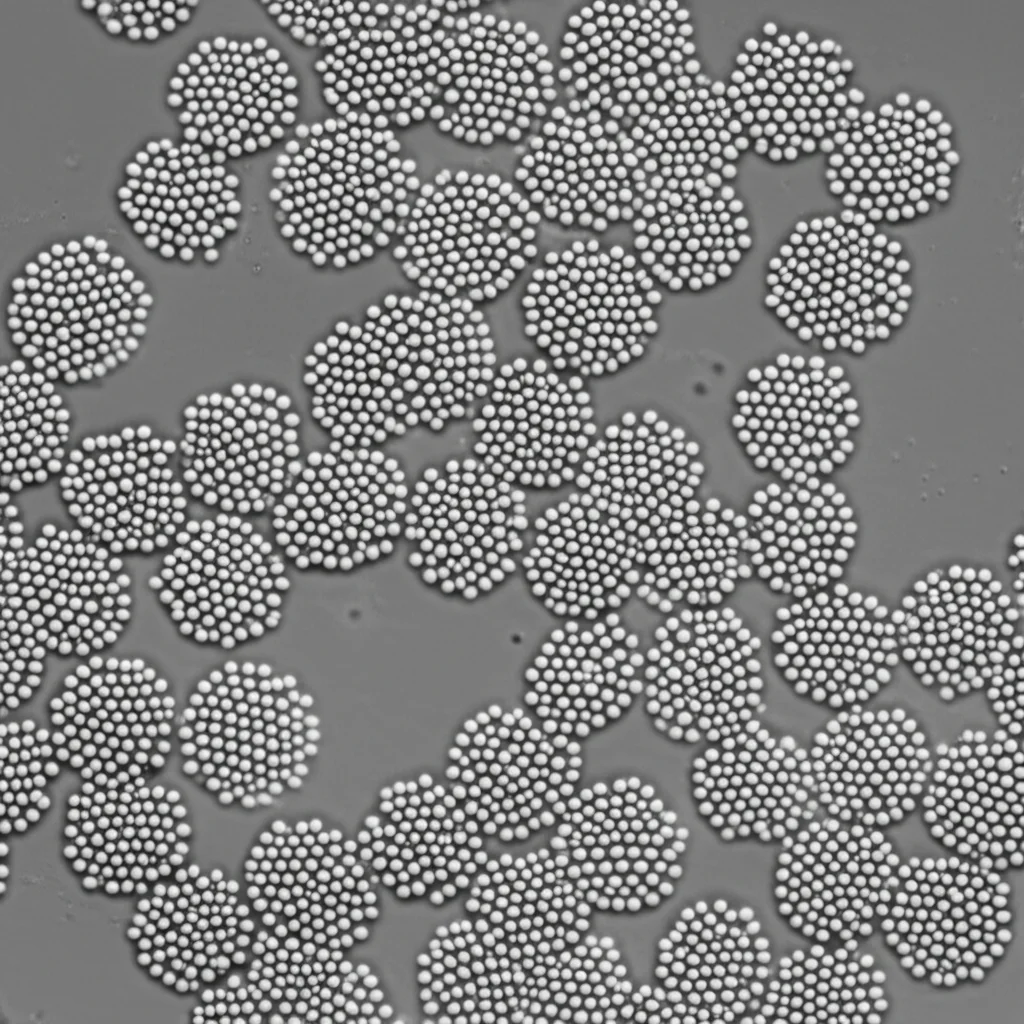

Our XRD results were great news – all our samples showed the pure spinel structure we were aiming for, with no unwanted impurities popping up (well, at least none that XRD could easily spot). The particles were indeed nano-sized, ranging from about 14 to 24 nanometers. That’s incredibly small!

We also noticed something interesting: as we added more Ho³⁺, the size of the crystal structure (the lattice parameter) slightly increased. This makes sense because the Ho³⁺ ion is bigger than the Fe³⁺ ion it’s replacing. It’s like trying to fit a slightly larger brick into a wall – it expands things a bit.

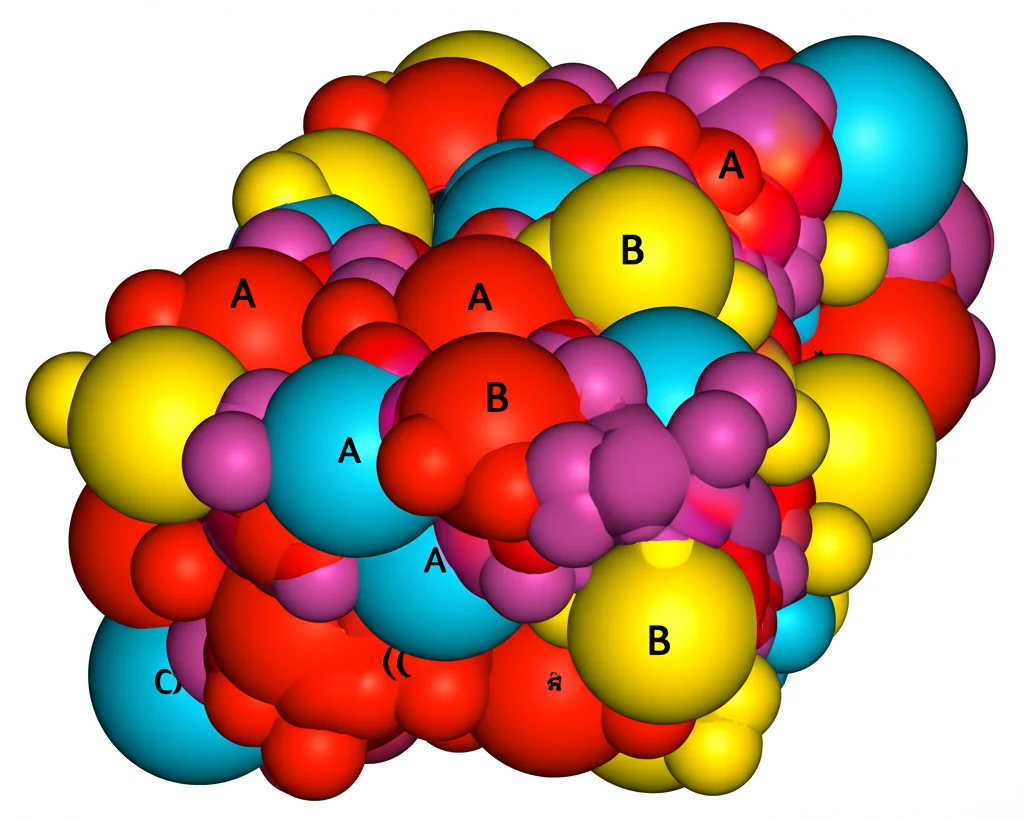

Using the XRD data, we could even figure out where the different metal ions preferred to sit within the spinel structure’s two main spots: the tetrahedral (A) sites and the octahedral (B) sites. We found that the larger Ho³⁺ ions *exclusively* settled into the B-sites. This is typical for larger rare earth ions because the B-sites offer more space. The Nickel and Cobalt ions mostly went to the B-sites too, which is expected for this type of spinel, but some also ended up in the A-sites. The Iron ions, being more flexible, spread out across both A and B sites. This cation distribution is a big deal because it directly influences the material’s properties.

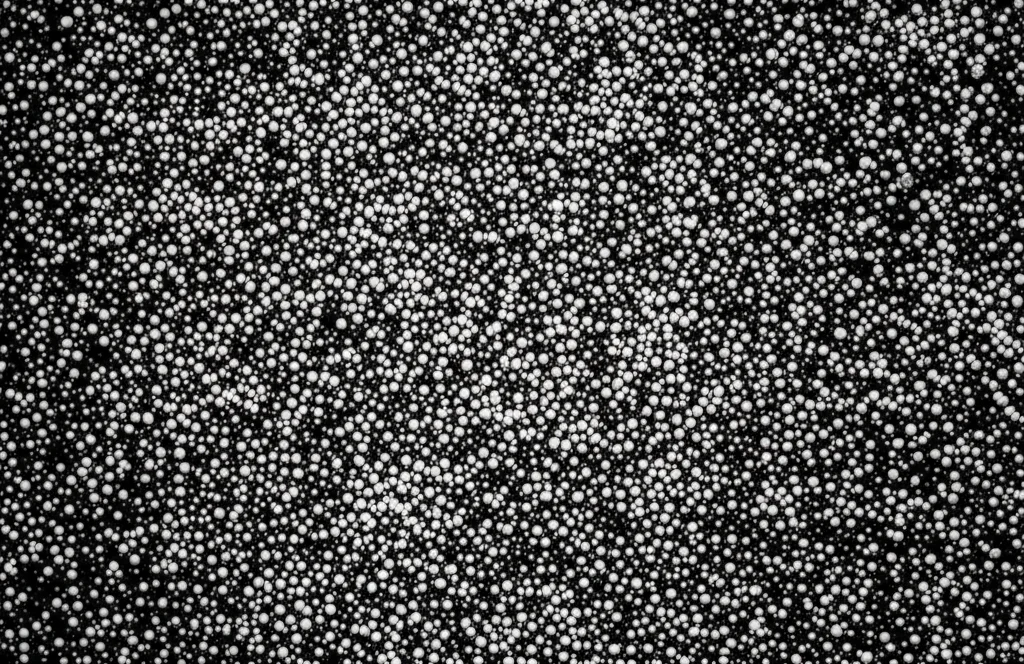

Our SEM images showed that the nanoparticles were mostly spherical, but they tended to clump together a bit. This aggregation is pretty common for nanoparticles and can affect their overall behavior, especially magnetic interactions between them. The EDX analysis confirmed that all the elements we expected – Cobalt, Nickel, Holmium, Iron, and Oxygen – were present in the samples. HR-TEM gave us even finer details, showing the crystal lattice planes and confirming the spinel structure at the atomic level.

Getting Magnetic: Hardness and Changing Moments

Now for the magnetic fun! We measured how magnetic the samples got when we applied a magnetic field, both at room temperature (300 K) and at a super-cold temperature (10 K). The results showed that our Ho-doped Ni-Co ferrites are “hard magnetic” materials with “ferrimagnetic” behavior. “Hard magnetic” means they hold onto their magnetism pretty strongly even after the external field is removed (think refrigerator magnets, but much stronger at the nanoscale!).

We looked at a few key magnetic parameters:

- Saturation Magnetization (Ms): How magnetic the material gets when the field is strong enough to align all the magnetic moments.

- Coercivity (Hc): The strength of the magnetic field needed to completely demagnetize the material.

- Magnetic Moment (nB,obs): The average magnetic strength per formula unit.

Interestingly, as we added more Ho³⁺, the saturation magnetization (Ms) *decreased*. This might seem counterintuitive because Holmium itself has a high magnetic moment, especially at low temperatures. However, at room temperature, Holmium is paramagnetic, meaning its magnetic moments aren’t ordered. More importantly, the substitution of Ho³⁺ for Fe³⁺, especially at the B-sites, seems to weaken the magnetic interactions between the A and B sites (the “super-exchange interactions”), which are crucial for the overall magnetism in these ferrites. Also, the cation redistribution we saw (where some Ni and Co might shift sites) and the potential formation of tiny, non-magnetic or anti-magnetic impurity phases at higher Ho concentrations could contribute to this drop in Ms.

On the flip side, the coercivity (Hc) *increased* significantly with more Ho³⁺ doping. This means they became *harder* to demagnetize. Why? Several factors could be at play: the changes in cation distribution, distortions in the crystal lattice caused by the larger Ho³⁺ ions, the decrease in the size of the individual crystallites (smaller grains often mean higher coercivity), and an increase in the boundaries between these grains (which can pin down magnetic domain walls, making them harder to move). The strong interaction between the magnetic moments and the crystal lattice (magnetocrystalline anisotropy), enhanced by the presence of Ho³⁺ and Co²⁺ ions, also plays a big role in boosting Hc.

We also looked at the “squareness” of the magnetic loops. At room temperature, the values suggested the samples had a “multi-magnetic domain” structure (like tiny magnetic regions pointing in different directions). But at the super-cold 10 K, the values indicated a “single ferromagnetic domain” structure, where the magnetism is more uniformly aligned within each nanoparticle.

Microwave Magic: Absorbing Waves

Spinels are also great for interacting with electromagnetic waves, especially microwaves. We tested our samples in the 12–33 GHz range, which is relevant for many high-frequency applications. We measured how the material affected the electric field (permittivity) and the magnetic field (permeability) of the microwaves passing through.

The actual part of the permittivity (related to how much electric energy the material stores) generally increased as we added more Ho³⁺. The imaginary part (related to electric energy loss) showed more complex behavior with peaks in certain frequency ranges. This interaction with the electric field is mainly due to how the electron shells and ions in the material respond to the oscillating electric field of the microwave – basically, they polarize.

For permeability (how much magnetic energy the material stores or loses), the actual part showed interesting frequency dependence, especially increasing in the lower part of the tested range for doped samples. This is linked to the magnetization processes within the material. The imaginary part (related to magnetic energy loss) also varied with frequency and Ho content, showing different patterns for low vs. high doping levels, which is related to resonant magnetic absorption, like natural ferromagnetic resonance.

Perhaps the most practical result for applications like microwave absorbers is the reflection coefficient (RL). This tells us how much of the incoming microwave energy is reflected versus absorbed. Negative values mean energy is absorbed. Our samples showed significant absorption! The undoped sample (x=0.00) had the strongest absorption peak at 17.8 GHz, reducing the reflected energy by over 39 times! As we added Ho³⁺, this peak shifted slightly and became less intense.

Interestingly, our analysis suggested that the main reason for the microwave absorption in these samples is the *electric energy losses* (related to permittivity and polarization), rather than purely magnetic losses. This is a key finding for designing devices using these materials.

Hyperfine Insights: Peeking at the Atoms

Finally, we used Mössbauer spectroscopy, a technique that lets us look at the local environment around the Iron atoms and understand the magnetic interactions happening right there. The spectra confirmed that the Iron atoms were in the Fe³⁺ state. The patterns we saw indicated that the Ho³⁺ ions were indeed substituting for Fe³⁺ ions specifically at the B-sites, supporting what we found with XRD.

The Mössbauer data also showed that the magnetic field experienced by the Iron nuclei (the “hyperfine magnetic field”) decreased as we added more Ho³⁺. This lines up nicely with the decrease in overall magnetization we observed. It further supports the idea that the Ho³⁺ substitution weakens those crucial A-B super-exchange interactions. Other factors like the size of the nanoparticles and how the spins might be slightly tilted (“spin canting”) also contribute to this reduced field.

At higher Ho concentrations (x=0.04 and 0.05), we even saw signs of superparamagnetism in the Mössbauer spectra. This happens when nanoparticles are so small that their magnetic moments can randomly flip direction due to thermal energy, making them behave differently magnetically.

So, Why Does This All Matter?

Putting it all together, our little adventure in doping Ni-Co spinel ferrites with Holmium was quite revealing! We successfully made these nano-sized materials using a straightforward method. We confirmed that the Ho³⁺ ions go into the B-sites, which significantly changes how the other atoms are distributed. These structural changes, in turn, dramatically impact the magnetic and microwave properties.

We saw the overall magnetization decrease (likely due to weakened interactions and cation shifts) but the coercivity increase (making them magnetically harder). We also found they are effective microwave absorbers, with electric losses playing a major role.

These tailored properties make these Ho-doped Ni-Co spinel ferrites really promising candidates for a bunch of cool applications. Think better microwave absorption materials for stealth technology or reducing electronic interference, components for high-density data storage, or even advanced sensors and electronic devices. By carefully controlling the amount of Ho doping, we can tune these properties for specific needs. It just goes to show how adding a tiny bit of a special ingredient can unlock a whole world of possibilities in materials science!

Source: Springer