High-Intensity Training and HCM: Is It Finally Safe?

Hey Everyone, Let’s Talk About Your Heart and Exercise!

You know, for a long time, if you had a condition called Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy (HCM), the general advice was pretty straightforward: take it easy, especially when it comes to intense exercise. HCM is a common inherited heart issue, and it can cause some serious problems, like making your heart muscle thick and increasing the risk of scary stuff like heart failure or sudden cardiac death. So, the caution around vigorous activity, including competitive sports, made sense on the surface. The worry was that pushing yourself too hard could make things worse or trigger a dangerous event.

But Wait, Are the Rules Changing?

Things have been shifting a bit lately. Thanks to better research, the guidelines around exercise for HCM patients have started to loosen up. Mild to moderate exercise is now generally considered okay, even getting a Class I recommendation (that’s like, the highest level of evidence saying “go for it, it’s good!”). High-intensity stuff and competitive sports are still a bit more cautious, sitting at a Class 2b recommendation, which means the benefits might outweigh the risks in some cases, but it’s less certain.

We’ve seen studies suggesting that even athletes with genetic heart problems can keep competing with careful management. And some research hinted that high-intensity interval training (HIIT) could be really good for heart health in other conditions like heart failure or hypertension. But for HCM specifically, the picture on whether high-intensity training (let’s call it HIT for short) is truly safe and effective has been a bit fuzzy.

Enter the Systematic Review!

So, this is where this cool systematic review comes in. The folks behind it wanted to take a good, hard look at all the available studies – both experimental and observational – to see what HIT really does to patients with HCM. They followed a strict process (like PRISMA guidelines, if you’re into that sort of thing) and searched through a bunch of medical databases to find relevant research published up to March 2024.

They started with a massive list of 1418 studies! After weeding out duplicates and irrelevant papers based on titles and abstracts, they were left with 14 full articles to check out. After a careful read, they ended up with just four studies that met all their criteria. These four studies included a total of 2008 patients, which gives us a decent sample size to look at.

They also checked the quality of these studies using a tool called EPHPP, and honestly, they found that three out of the four studies were considered “weak” quality. This is important to keep in mind – it means we should interpret the findings with a bit of caution, and it definitely highlights the need for more high-quality research in this area.

Defining “High-Intensity Training”

One of the tricky things the review noted was that the definition of “high-intensity training” wasn’t exactly the same across all the studies. Generally, it meant vigorous exercise requiring a high level of effort, often measured by metabolic equivalents (METs) or heart rate. For example:

- Some studies defined vigorous exercise as ≥ 6 METs (like jogging) or athletes doing ≥ 4 hours/week for years.

- Others looked at structured interval training at 90-95% of peak heart rate.

- Another defined it as regular athletic training for 2+ hours per session, three times a week, totaling 6-14 hours of vigorous exercise weekly, often competitive.

The comparator groups usually did lower intensity exercise, moderate activity, or were sedentary/non-athletes.

So, What Did They Find? The Good News!

Here’s the really interesting part. When they compared the HIT/vigorous exercise groups to the lower-intensity/sedentary groups, they found some significant differences, and they were mostly positive for the high-intensity folks:

- Better Heart Filling: HCM athletes had higher Left Ventricular End-Diastolic Volume (LVEDV). Think of this as the main pumping chamber of your heart being able to hold more blood when it relaxes. This is pretty cool because HCM often makes this chamber stiff and less able to fill properly. A higher LVEDV suggests better diastolic function.

- Stronger Pumping: Along with better filling, they also had higher Stroke Volume (SV). This means the heart was pumping out more blood with each beat. More blood pumped per beat can lead to better overall circulation and potentially improved exercise capacity.

- Reduced Obstruction: This is a big one! The Left Ventricular Outflow Tract (LVOT) gradient was significantly *lower* in the vigorous exercise group compared to the non-vigorous group, both at rest and when provoked. The LVOT gradient is basically a measure of how much the thickened heart muscle is blocking blood flow out of the ventricle. A lower gradient means less blockage, which can really help with symptoms like shortness of breath and chest pain.

What About the Worries? Safety Check!

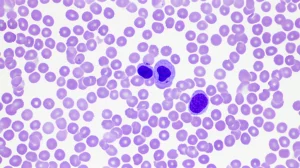

Now, the biggest concern with HIT in HCM is safety – specifically, the risk of life-threatening arrhythmias, cardiac arrest, or even death. This review looked specifically at that, and guess what? They found no significant differences in arrhythmias (like NSVT, VT, VF, or syncope), cardiac arrest, or mortality between the HIT groups and the comparator groups.

This is a pretty powerful finding! It suggests that, based on these studies, doing high-intensity training didn’t increase the risk of these serious adverse events compared to doing less intense exercise or being sedentary. This really challenges that traditional fear.

Vital Signs and Aerobic Capacity

Interestingly, the review didn’t find significant differences between the groups in vital signs like blood pressure (SBP, DBP) or maximum heart rate. They also didn’t see a *meaningful* improvement in VO2 max (a key measure of aerobic fitness) in their calculation, even though some previous studies *have* shown VO2 max improvements with HIT in other populations. The review authors suggested this might be due to the limitations of the included studies, like sample size or the different ways HIT was defined.

However, the improvements they *did* see in LVEDV and SV *do* suggest a potential for improved exercise capacity, even if the direct VO2 max numbers weren’t statistically striking in this specific analysis. The idea is that a heart that fills and pumps better *should* be able to handle more activity.

Putting It All Together

So, the big takeaway from this systematic review is pretty exciting. It suggests that high-intensity exercise, when done by patients with HCM, seems to lead to some really positive changes in how the heart works – specifically, better filling, stronger pumping, and less obstruction to blood flow. And crucially, these benefits didn’t come with an increased risk of serious problems like arrhythmias or cardiac arrest compared to less intense activity.

Now, remember those study quality limitations? They mean we can’t say this is the absolute final word on the subject. We definitely need more high-quality research, ideally larger studies with consistent definitions of HIT and longer follow-up periods, to really confirm these findings and understand the long-term effects.

What Does This Mean for Patients and Guidelines?

These findings are a strong argument for rethinking the current guidelines on physical activity restrictions for people with HCM. It seems like a blanket restriction on high-intensity exercise might be too cautious for everyone. Under appropriate medical supervision and with careful evaluation, it looks like HIT could be a safe and effective way for many HCM patients to improve their heart health and overall fitness.

It’s a nuanced approach, recognizing the potential benefits while still emphasizing the need for careful management. This review is a significant step in building the evidence base to support that shift.

Source: Springer