Choosing Your Hemodialysis Lifeline: What the Science Says About Access, Healing, and Survival

Hey there! Let’s talk about something super important for folks dealing with end-stage renal disease (ESRD) – getting hemodialysis. If you or someone you know is on this journey, you know that connecting to the dialysis machine is literally a lifeline. But did you know *how* that connection is made can make a big difference? I’ve been looking into a fascinating study that dives deep into this very thing, and I wanted to share what I learned in plain English.

So, ESRD is a big deal worldwide. It means the kidneys aren’t doing their job anymore, and dialysis steps in to filter the blood. Hemodialysis is the most common type, and for it to work, you need reliable access to your bloodstream. Think of it like the port you plug into – if the port isn’t good, the connection is shaky, right? In the medical world, this access point is crucial, often called the patient’s “lifeline.”

But, as with anything medical, there are different ways to create this lifeline, and each has its pros and cons. This study, a look back at data from 323 ESRD patients over ten years, compared the three main types of hemodialysis access:

The Lifeline Explained

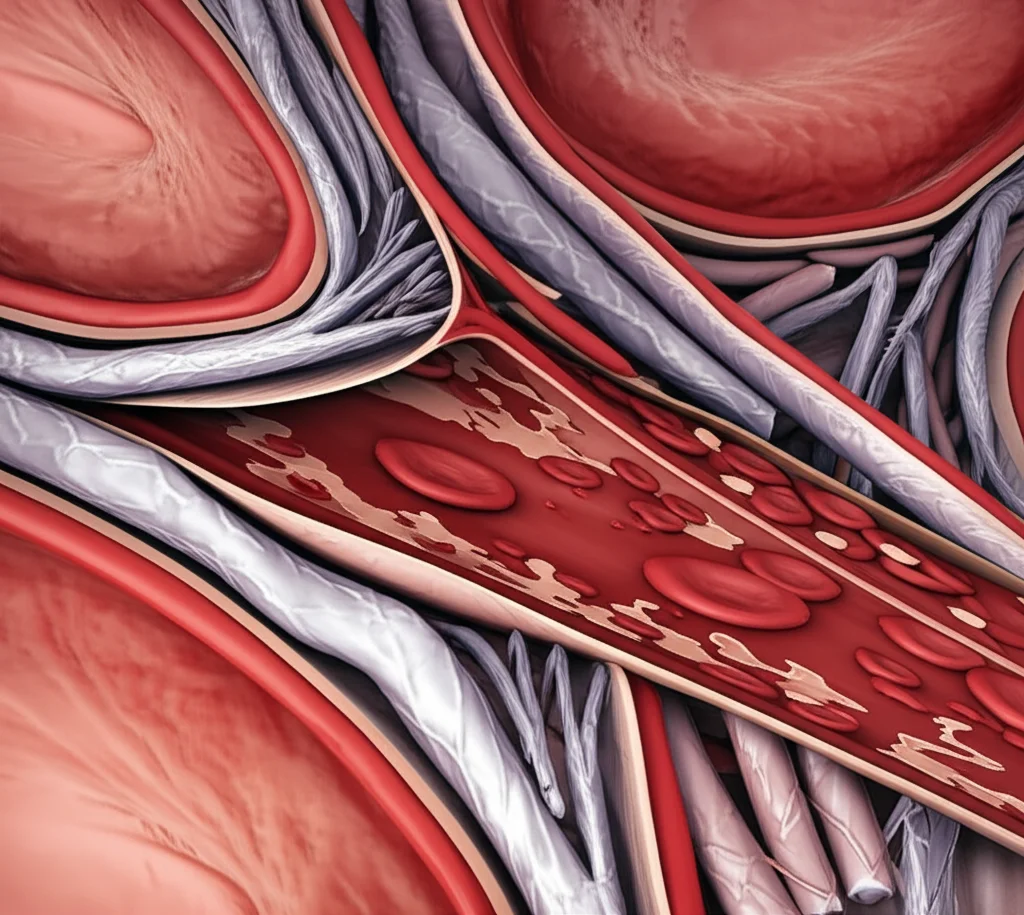

- Autologous Arteriovenous Fistula (AVF): This is often the gold standard. It’s created surgically by connecting one of your own arteries and veins, usually in the arm. It takes time to mature before it can be used, but it’s generally the most durable and has fewer complications in the long run.

- Arteriovenous Graft (AVG): If your own vessels aren’t suitable for an AVF, doctors might use a graft. This involves surgically implanting a piece of artificial tubing (like polytetrafluoroethylene) to connect an artery and a vein. It can be used sooner than an AVF but tends to have more issues like clotting or infection.

- Central Venous Catheter (CVC): This is a tube inserted into a large vein, usually in the neck, chest, or groin, with the tip going into a central vein near the heart. CVCs are often used for temporary access or when AVF/AVG isn’t possible or ready. They are quick to place but have the highest risk of infection and other complications.

For years, doctors have known that AVF is generally preferred, but getting solid data comparing all three across multiple outcomes – not just if they work, but how well wounds heal, how many problems pop up, and how long patients live – has been a bit limited. That’s where this study comes in.

What the Study Looked At

This retrospective study (meaning they looked back at existing patient records) aimed to fill that gap. They wanted to see how these three access types stacked up when it came to:

- Wound healing time: How quickly did the surgical site close up?

- Complication rates: How often did things like infections, clotting, or needing another surgery happen?

- Dialysis efficacy: How well did the access allow for effective blood filtering? (Measured by things like how much urea nitrogen was removed).

- Cardiac function: Did the access type affect the heart?

- Survival: How long did patients live after getting their access?

They split the 323 patients into three groups based on their access type: AVF, AVG, and CVC. They also noted things like age, BMI, and underlying conditions, including chronic glomerulonephritis and whether patients were on immunosuppressive therapy, as these can influence outcomes.

The Nitty-Gritty: What They Found

Okay, let’s get to the good stuff – the results! And honestly, some of it confirms what doctors suspected, while other parts give us clearer numbers.

First off, when it comes to keeping the access working (what they call patency rates), the AVF group was the clear winner. AVF accesses stayed open and usable for longer without needing interventions compared to AVG and especially CVC. This makes sense because it’s using your own natural vessels.

Now, about wound healing. This was a bit counter-intuitive at first glance. The CVC group actually had the *shortest* wound healing time. Why? Because inserting a catheter is a less invasive procedure than creating a surgical fistula or implanting a graft. However, and this is a big however, the CVC group had the *highest* rates of infection and needing another operation (reoperation rate). The AVG group was in the middle, and the AVF group had the lowest infection and reoperation rates. So, quicker healing with CVC came with a much higher price tag in terms of problems.

When they looked at how effectively dialysis was clearing waste products from the blood (dialysis efficacy), the AVF group again came out on top. They had significantly better urea nitrogen reduction and clearance rates, and better blood flow through the access. This means AVF allows for more efficient dialysis sessions, which is crucial for long-term health.

Interestingly, the study didn’t find significant short-term differences in cardiac function (like how well the heart pumps) among the three groups. This is a bit different from some previous ideas that AVFs might put more strain on the heart due to higher blood flow, but the researchers noted their study had a shorter observation period for this and a limited sample size, so maybe the long-term effects weren’t captured here.

Now, for the really critical part: survival. While there weren’t significant differences in deaths from specific causes like heart attacks, strokes, or infections when looked at individually, there *was* a significant difference in *all-cause* mortality (deaths from any reason) and overall survival time among the groups.

The AVF group had the longest median survival time (around 371 days in this study), followed by the CVC group (around 363 days), and then the AVG group (around 352 days). Wait, the CVC group had shorter healing and more complications, but longer survival than AVG? The study notes that while CVC has high infection risks, AVF’s long-term stability and superior dialysis efficiency likely contribute to better overall outcomes and longer survival for *suitable* patients. The AVG group, often used when AVF isn’t ideal, seemed to fare slightly worse in median survival compared to both AVF and CVC in this specific study’s timeframe, though the differences between CVC and AVG median survival were quite close.

The researchers emphasize that the longer survival with AVF likely comes down to its stability, lower complication rates, and the fact that it allows for more effective removal of toxins over time. This improved toxin removal translates to a better quality of life and potentially longer life expectancy for patients who can get and maintain an AVF.

Why Does This Matter?

So, what’s the big takeaway from all this? It reinforces that the type of hemodialysis access isn’t just a technical detail; it has real, tangible impacts on a patient’s journey. AVF, when possible, appears to be the best option for long-term dialysis because it works better and leads to fewer problems and longer survival. It’s the most robust “lifeline.”

However, and this is key, not everyone is a candidate for an AVF. Some patients have poor blood vessels, are older, or have other health issues that make AVF creation difficult or risky. In those cases, AVG or CVC become necessary alternatives. The study highlights that even though CVCs heal faster initially, their high infection and reoperation rates are a major drawback. Patients with conditions like chronic glomerulonephritis or those on immunosuppressive therapy might be at even higher risk of infection, especially with CVCs, which is something doctors need to be extra careful about.

The fact that AVF showed superior dialysis efficacy – getting more of the bad stuff out of the blood – is a really important finding. It’s not just about having an access point; it’s about how *well* that access point allows the dialysis machine to do its job. Better clearance means better overall health for the patient.

The Big Picture

Ultimately, this study adds more weight to the recommendation that AVF should be the preferred access type whenever clinically appropriate. It offers the best chance for effective dialysis, fewer complications, and a longer, better quality of life. But it also reminds us that medicine isn’t one-size-fits-all. Choosing the right “lifeline” for each patient requires a careful look at their individual health, their blood vessels, and their overall prognosis. It’s a decision that needs to be made collaboratively between the patient and their healthcare team, weighing the benefits of the ideal option against the realities of the patient’s specific situation.

For patients and their families, understanding these differences is empowering. It allows for more informed conversations with doctors about the best path forward. While the journey with ESRD and hemodialysis is challenging, knowing that the choice of access can significantly impact outcomes offers a focus for optimizing care.

This research gives us clearer data points on why AVF is the preferred route and underscores the challenges and trade-offs associated with AVG and CVC. It’s a valuable piece of the puzzle in helping healthcare providers and patients make the best possible decisions for that all-important lifeline.

It’s a complex picture, but studies like this help clarify the landscape, guiding us toward better outcomes for everyone needing this vital treatment.

Source: Springer