Gut Guardians: How GSDMD Pores Put the Brakes on IL-18 Production

Hey there! Let me tell you about something pretty fascinating happening right inside your gut. You know, that amazing barrier lining your intestines? It’s not just sitting there; it’s actively defending you, and it uses some clever tricks to keep things balanced. We’ve been digging into one of these tricks, and it involves some key players: inflammasomes, a protein called Gasdermin-D (GSDMD), another one called Caspase-4, and a crucial signaling molecule called IL-18.

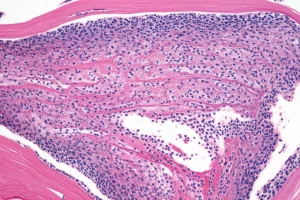

Setting the Stage: Inflammasomes and the Gut Barrier

So, think of inflammasomes as tiny alarm systems inside your cells. When they detect trouble – like invaders or signs of damage – they kick into gear. One of the main things they do is activate certain proteins called caspases. These activated caspases are like molecular scissors. They snip other proteins, including GSDMD and important signaling molecules like IL-18 and IL-1β.

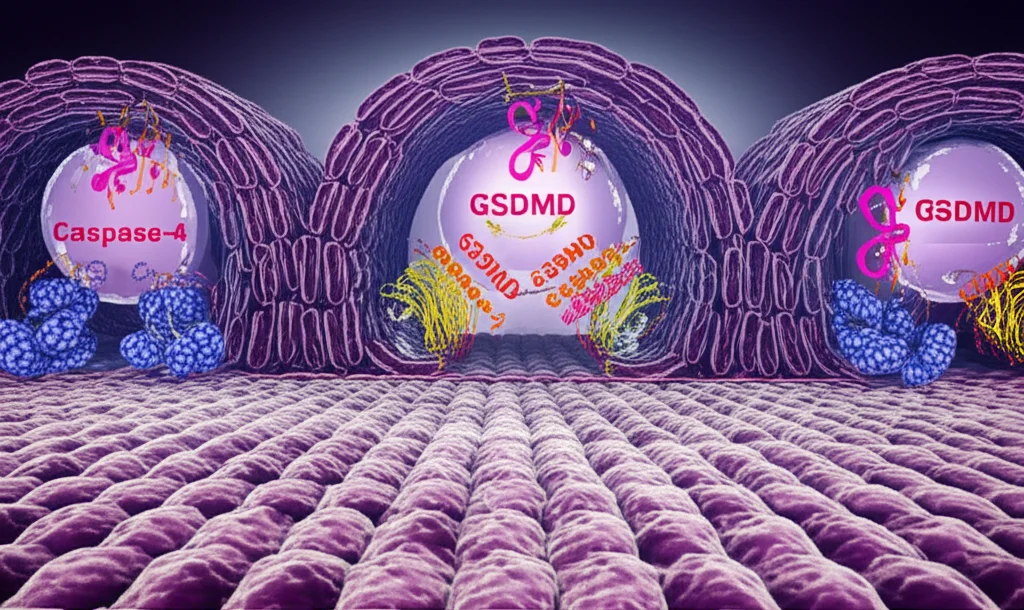

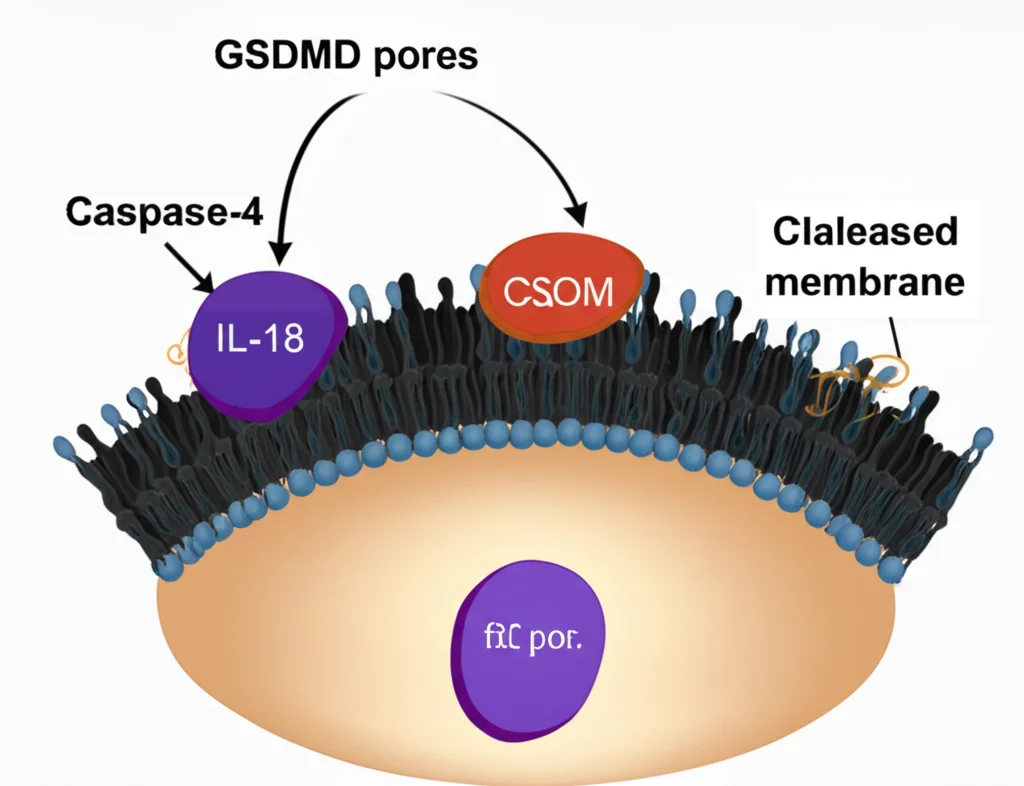

When GSDMD gets snipped, its active part forms pores, or tiny holes, in the cell’s outer membrane. These pores are super important because they let those snipped, active IL-18 and IL-1β molecules escape the cell to signal to other immune cells. It’s like opening a tiny gate to send out messengers.

But here’s the catch: these GSDMD pores can also lead to a type of inflammatory cell death called pyroptosis. In immune cells, like the ones that patrol your blood, this is often a good thing. A dying immune cell can trap bacteria and send out signals to call for backup. It’s a messy but effective way to contain an infection quickly.

Now, the gut lining is different. It’s a barrier! Rapid cell death here could be disastrous, creating gaps that invaders could sneak through. So, how do the cells in your gut lining manage to use this GSDMD pore system to release helpful IL-18 without completely falling apart? That’s the big question we were tackling.

In human gut epithelial cells, Caspase-4 seems to be a really key player in this whole process. It’s important for fighting off certain bacteria and releasing IL-18. But if activating Caspase-4 leads to GSDMD pores and cell death, how can it also release IL-18 *and* keep the barrier intact?

The Puzzle: Balancing Act

For a long time, the thinking was that once a cell went down the pyroptosis path, that was it – signaling stopped, and the cell died. End of story. But newer research is showing that cells are way more sophisticated. They have ways to *modulate* this process, to maybe form pores but *not* necessarily die right away, or to repair the pores. It’s like they can control the volume knob on the pyroptosis signal.

Some ideas involve cells patching up the GSDMD pores. But even that doesn’t fully explain how the cell might *turn off* the signal or fine-tune the amount of cytokine released. This fine-tuning seems especially critical in places like the gut lining, where you need to release signals to fight infection but absolutely minimize damage to the barrier.

Our Investigation Begins

So, we set out to really understand how Caspase-4 is regulated in human intestinal epithelial cells, specifically looking at its role in IL-18 production. We used different human intestinal cell lines and even primary human gut organoids (which are like mini-guts grown in the lab – pretty cool!). We triggered their inflammasomes, often using a component of bacterial walls called LPS, delivered right inside the cell.

What we expected was that more Caspase-4 activity would mean more IL-18 production. And initially, we saw that activating the inflammasome did lead to IL-18 release and GSDMD getting snipped and forming pores, just like the textbooks say.

But then we noticed something totally unexpected. When we looked at cells where GSDMD was missing or knocked down, they actually produced *way more* mature IL-18 than normal cells! This was a head-scratcher. GSDMD pores are supposed to *release* IL-18, so how could *less* GSDMD lead to *more* IL-18 being made? It was like removing the exit gate somehow boosted production inside the factory.

The GSDMD Connection

We confirmed this finding in multiple ways – using different cell lines and those primary human organoids. Every time, reducing GSDMD levels led to less cell lysis (less pyroptosis, which made sense) but significantly *increased* the amount of mature IL-18 produced.

We also checked if this was a general thing or specific to gut cells. We did similar experiments in human immune cells (THP1 monocytes). In these cells, knocking down GSDMD *did* reduce cell lysis, but it only had a minimal effect on IL-18 production compared to the dramatic increase we saw in the gut cells. This told us that GSDMD’s effect on IL-18 maturation is really something special happening in the intestinal epithelium.

Unpacking Caspase-4 Cleavage

Scientists often measure caspase activation by looking for the smaller pieces that result when the caspase protein is cut, or cleaved. For Caspase-4, previous studies had reported cleavage into p31 and p33 fragments. We thought maybe in our GSDMD-deficient cells, Caspase-4 was just more active and getting cleaved more, leading to more IL-18.

So, we looked for Caspase-4 cleavage in our gut cells after triggering the inflammasome. In normal cells (with GSDMD), we saw a reduction in the full-length Caspase-4 and the appearance of a cleavage fragment. But it wasn’t the p31 or p33 we expected! It was a fragment around 37 kDa – let’s call it p37 Caspase-4.

Here’s the kicker: in the GSDMD-deficient gut cells, where we saw *more* IL-18 production, we saw *no evidence* of this p37 Caspase-4 fragment forming. This was totally counterintuitive! More IL-18 was happening when Caspase-4 *wasn’t* being cleaved into this p37 form.

We then looked at the immune cells again. In THP1 monocytes, we *did* see a Caspase-4 fragment, but it was the previously reported p31, and it appeared regardless of whether GSDMD was present or not. This further highlighted that Caspase-4 processing is different in gut epithelial cells compared to immune cells, and in gut cells, GSDMD seems necessary for the formation of that p37 fragment.

It started to look like the p37 cleavage wasn’t a sign of *activation* leading to more IL-18, but maybe the opposite – a sign of *inactivation* or regulation.

Full-Length Caspase-4 is the Star

This led us to a bold idea: maybe the *full-length* Caspase-4 protein is the one that’s really good at processing IL-18, and maybe getting cut into that p37 fragment *limits* its ability to do that.

To test this, we did some experiments where we put Caspase-4 and IL-18 into cells that don’t normally have them (HEK293T cells). By overexpressing them, we could trigger Caspase-4 activity without GSDMD pores or cell death getting in the way. We also created versions of Caspase-4 that couldn’t be cleaved at certain spots or had their catalytic (cutting) ability turned off.

What we found strongly supported our idea. Caspase-4 was definitely needed to process IL-18. But when we used a version of Caspase-4 that was designed *not* to be cleaved at the standard sites (or our newly observed p37 site), it produced *much higher* levels of mature IL-18 compared to the normal, cleavable version. This suggested that keeping Caspase-4 in its full-length form is key for maximum IL-18 processing.

It’s About the Pores, Not Just Death

Okay, so GSDMD limits IL-18 production by somehow causing Caspase-4 to be cleaved into p37. But what *aspect* of GSDMD is doing this? Is it the cell death itself? Or is it the formation of the pores?

We did experiments to separate these things. We used methods to prevent cell lysis (the cell bursting open) even though GSDMD pores were still forming. In these cases, we still saw the p37 Caspase-4 fragment appear, and IL-18 production was still limited. This told us that the p37 cleavage and the limitation of IL-18 weren’t just happening because the cell was dying and falling apart.

Then, we used a chemical (DMF) and specific GSDMD mutations that prevented the GSDMD protein from inserting into the plasma membrane and forming functional pores, even though GSDMD was still being cut by Caspase-4. When we blocked GSDMD pore formation like this, we saw *less* of the p37 Caspase-4 fragment, and importantly, *more* total IL-18 production.

We even did some careful timing experiments. We saw that cellular viability dropped pretty quickly after triggering the inflammasome, even if pores weren’t forming. But the cells that *didn’t* form GSDMD pores (and thus didn’t have the p37 Caspase-4 cleavage) continued to produce IL-18 for a longer time, despite the initial hit to their viability. This further supported the idea that it’s the *pore formation*, not just the general decline in cell health or death, that triggers the Caspase-4 cleavage and limits IL-18.

We used different GSDMD mutants in our HEK293T system. Some mutants still reduced cell viability but didn’t form plasma membrane pores. Others formed pores but didn’t reduce viability as much. The results consistently showed that the *ability to form plasma membrane pores* was what correlated with reduced IL-18 production and increased Caspase-4 cleavage, independent of the effect on overall cell viability.

The Search for the Cleaver

So, if GSDMD plasma membrane pore formation causes Caspase-4 to be cleaved into p37, what’s doing the cutting? We tried blocking several usual suspects – processes like autophagy, certain enzymes called cathepsins, reactive oxygen species, calcium influx, and the proteasome. None of these seemed to be responsible for the p37 cleavage or its effect on IL-18.

We know that stress in a part of the cell called the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) can cause Caspase-4 cleavage. We did see a p37 fragment when we induced ER stress chemically. This is an intriguing possibility – maybe GSDMD pore formation somehow causes ER stress, which then leads to Caspase-4 cleavage? We looked for signs of ER stress after triggering GSDMD, but didn’t find clear evidence *yet*.

Our current best guess is that GSDMD plasma membrane pore formation activates some *other*, as-yet-unknown protease that specifically cuts Caspase-4 into that p37 form in gut epithelial cells. Finding this mystery protease is a big next step!

Infection Confirms the Story

To make sure this wasn’t just an artifact of using LPS in the lab, we infected our human gut organoid monolayers with a type of bacteria called *Shigella flexneri*. This bacterium is known to trigger Caspase-4 and GSDMD.

Just like with the LPS experiments, when we infected normal gut cells (with GSDMD), we saw the p37 Caspase-4 fragment appear. But in the GSDMD-deficient cells, we didn’t see the p37 fragment. And, crucially, the GSDMD-deficient cells produced and released *more* IL-18 during the infection.

This confirmed that this GSDMD-dependent regulation of Caspase-4 and IL-18 isn’t just a lab curiosity; it happens during a real bacterial infection in human intestinal epithelial cells.

The Big Picture: A Clever Feedback Loop

Putting it all together, here’s what we think is happening:

When inflammasomes are triggered in gut epithelial cells, Caspase-4 gets activated. This activated Caspase-4 (likely in its full-length form) starts processing IL-18 (making it active) and also cuts GSDMD, leading to pore formation. But here’s the brilliant feedback loop: the formation of those GSDMD *plasma membrane pores* sends a signal (we think by activating an unknown protease) that causes Caspase-4 to be cleaved into the p37 fragment. This p37 fragment is less active against IL-18, effectively putting the brakes on further IL-18 production.

Think of it like a thermostat. Caspase-4 turns up the heat (IL-18 production and pore formation). But once the “temperature” (pore formation) reaches a certain level, it triggers a signal that tells Caspase-4 to cool it down by getting cut into a less active form.

Why is this important? Well, for a couple of reasons:

- Firstly, it allows the gut cells to release IL-18 – a vital signal for immunity and barrier repair – using the GSDMD pore system, but without necessarily committing to full-blown, barrier-damaging pyroptosis right away. It’s a way to secrete cytokines from *live* or semi-viable cells.

- Secondly, if a tricky pathogen manages to block pyroptosis (and many can!), this feedback mechanism would be less active because fewer GSDMD pores are forming. This *lack* of inhibitory feedback could lead to *increased* IL-18 production, potentially amplifying the immune response even if the infected cell can’t be quickly removed by pyroptosis. It’s like a backup system to boost the alarm signal if the first line of cellular defense is compromised.

Looking Ahead

This work opens up some exciting new avenues. The biggest mystery is definitely identifying that protease that cleaves Caspase-4 into p37. Pinpointing that enzyme could reveal new targets for controlling inflammation in the gut.

Also, our data strongly suggests that full-length Caspase-4 is the main player for IL-18 processing in this context, which challenges some existing ideas in the field that focus on smaller Caspase-4 fragments. More work is needed to definitively confirm this using different experimental setups.

And remember how Caspase-4 cleavage looked different in gut cells versus immune cells? That suggests there might be cell-type specific ways of regulating Caspase-4 activity, which is super interesting.

In summary, we’ve uncovered a really neat, epithelial-specific feedback mechanism where GSDMD plasma membrane pores act as a signal to dial down Caspase-4 activity by causing a specific cleavage. This helps the gut lining fine-tune its IL-18 production, balancing the need to fight off threats with the absolute necessity of keeping that crucial barrier intact. It’s another reminder of just how complex and clever our cells are!

Source: Springer