Unpacking the Genetic Blueprint: How BP and BMI Affect Your Heart, Pathway by Pathway

Hey there! Ever wonder how something as complex as your blood pressure or body weight really messes with your heart? It’s not just one simple thing, right? Turns out, even the genetic signals linked to these traits are super complicated. They don’t all work through the same biological channels. This is where a cool technique called Mendelian Randomization (MR) comes in, but with a twist.

Normally, MR uses genetic variations (like SNPs – little differences in your DNA) as natural experiments to figure out if a risk factor *causes* a disease, rather than just being associated with it. Think of it like inheriting a tendency for higher BP, and then seeing if *that inherited tendency* leads to heart problems, bypassing all the lifestyle stuff that might confuse things in regular studies. It’s pretty neat because genetic variants are randomly assigned when you’re born, which helps avoid some common pitfalls like confounding factors or reverse causation.

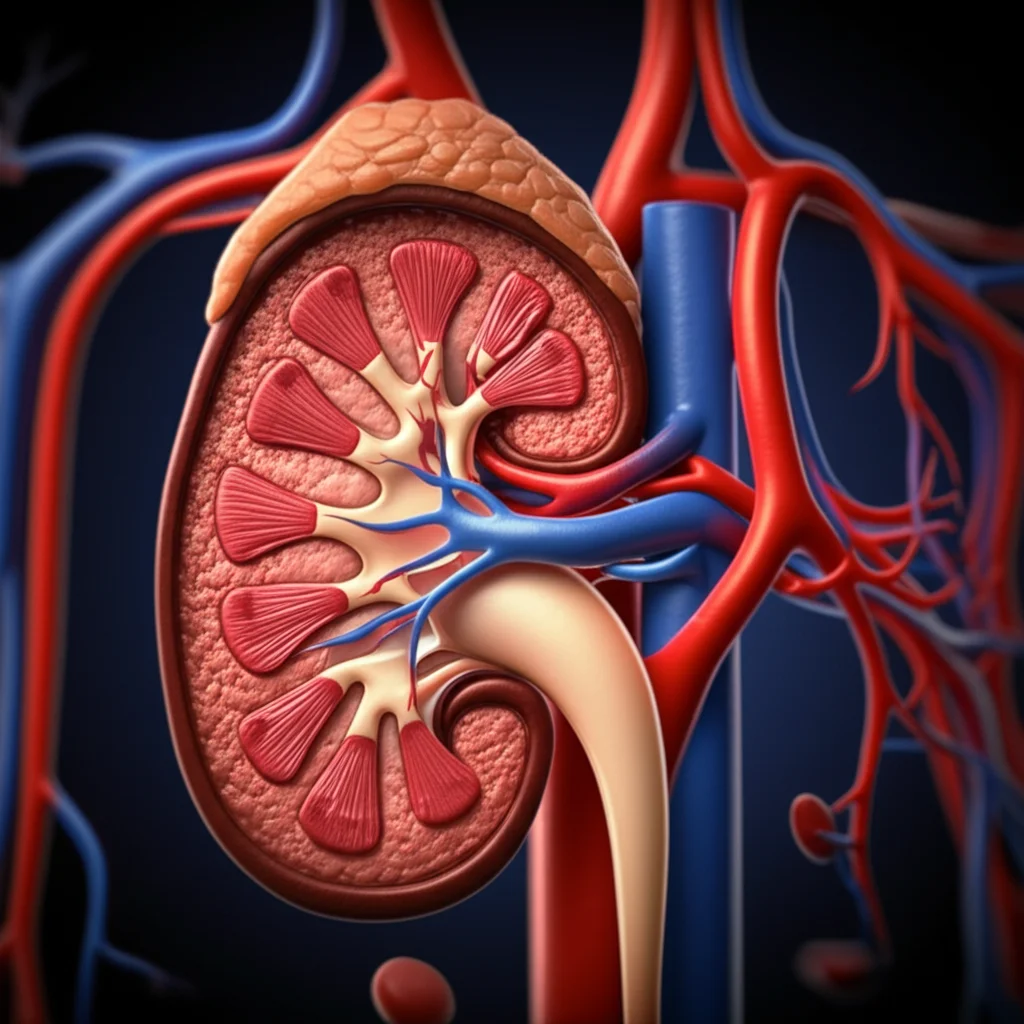

But here’s the rub: the genetic instruments for complex things like blood pressure or body mass index (BMI) are often a mixed bag. They can influence the trait (BP or BMI) through lots of different biological processes. This is called heterogeneity, and while it can sometimes mess up MR studies (that’s horizontal pleiotropy, where a gene affects the outcome through something *other* than the exposure you’re studying), it can also be a goldmine! If we can understand *which* genetic instruments work through *which* biological pathways or tissues, we can get a much clearer picture of how these traits lead to disease. It’s like figuring out if high BP damages your heart mainly through stiffening your arteries or messing up your kidneys.

Two Ways to Slice the Genetic Pie

So, how do we untangle this genetic mess? Scientists have been trying different ways to group these genetic instruments. Some methods cluster SNPs based on their associations with both the exposure and the outcome. Others look at how SNPs relate to a bunch of different traits. A really interesting approach groups SNPs based on where the genes they’re linked to are expressed in different tissues – like the brain or fat tissue for BMI.

In this study, we got a bit creative. We introduced a *new* way to group these genetic instruments, which we call pathway-partitioned MR. This method looks at whether the genetic instruments for a complex trait (like BP or BMI) are located near genes that cause rare, single-gene disorders (Mendelian diseases) with symptoms affecting specific biological systems or pathways. For blood pressure, we looked at genes linked to Mendelian diseases affecting the renal system (kidneys) or the vasculature (blood vessels). For BMI, we focused on genes linked to diseases affecting mental health or metabolic disorders. The idea is that if a genetic variant for high BP is near a gene that causes a kidney disease, maybe it affects BP primarily through kidney mechanisms.

We then stacked this new pathway approach up against an existing method, which we call tissue-partitioned MR. This older method groups SNPs based on whether they seem to affect gene expression (that’s called an eQTL) in specific tissues. For BP, this meant looking at gene expression in kidney or artery tissues. For BMI, it was adipose (fat) and brain tissues.

We used big datasets from genome-wide association studies (GWAS) – basically, massive scans of people’s DNA to find genetic variants linked to traits. We had data on hundreds of thousands of people for BP and BMI, and also for various cardiovascular outcomes like heart disease, stroke, and type 2 diabetes. We used different MR techniques, including looking at individual-level data (one-sample MR) and summary-level data (two-sample MR), and even multivariable models that let us look at the effects of different SNP groups at the same time.

To make sure our findings weren’t just random noise, we did some cool checks. We looked at a negative control outcome (age-related macular degeneration) that we didn’t expect to be affected by BP or BMI. We also ran simulations, randomly sampling SNPs to see how often we’d get differences in effects just by chance, comparing that to the differences we saw with our pathway and tissue groupings.

Blood Pressure, Vessels, Kidneys, and Your Heart

Okay, so what did we find when we applied these methods to blood pressure and heart-related traits?

First off, we confirmed what we already largely knew: higher genetically predicted BP is linked to a higher risk of coronary heart disease (CHD). But when we looked at our pathway-partitioned results, things got interesting. It seemed the link between both diastolic (DBP) and systolic (SBP) blood pressure and CHD was mostly driven by the genetic instruments linked to the “vessel” pathway, much more so than the “renal” pathway. The confidence intervals for these two groups of SNPs didn’t even overlap – that’s a pretty strong signal!

Now, here’s where it gets a bit twisty. When we looked at the tissue-partitioned results for CHD, the story was different. The genetic instruments linked to “nephro” tissue (kidney) actually showed a *stronger* effect on CHD risk compared to the “artery” tissue instruments. See? The pathway approach pointed to vessels, the tissue approach pointed to kidneys for CHD. This really highlights that these two ways of grouping SNPs capture different biological characteristics – one might be about the overall system function (pathway), the other about where the molecular action is happening (tissue).

We saw similar patterns for myocardial infarction (MI), which is closely related to CHD. The “vessel” pathway seemed more important than the “renal” pathway, though the tissue results for MI were a bit less clear-cut than for CHD.

Let’s talk about stroke volume (SV) – basically, how much blood your heart pumps with each beat. Genetically predicted DBP overall had a negative effect on SV (meaning higher DBP, lower SV). Both the “vessel” pathway and “artery” tissue instruments supported this negative effect. The “renal” pathway and “nephro” tissue instruments didn’t show a clear effect on DBP’s link to SV. For SBP, the overall effect on SV was positive. But our pathway analysis split the difference: “renal” pathway SNPs contributed to a positive effect, while “vessel” pathway SNPs actually had a *negative* effect on SV! No clear distinction was seen for tissue-partitioned SBP on SV. It’s complicated, right? Different genetic influences on BP seem to push SV in different directions depending on the pathway.

Blood Pressure, BMI, and Type 2 Diabetes

What about Type 2 Diabetes (T2D)? We know high BP is linked to T2D risk. Our overall MR results confirmed this. Looking at the pathways, the “vessel” pathway SBP instruments showed a higher risk of T2D than the “renal” pathway instruments, though the confidence intervals overlapped a bit here. For tissue partitioning, the “artery” tissue instruments (for both DBP and SBP) showed a clear positive link to T2D risk, while the “nephro” tissue instruments showed pretty much no effect. So, for T2D, both pathway (for SBP) and tissue approaches pointed towards the vascular side being more important than the kidney side.

Now, let’s switch gears to BMI. We looked at its effect on atrial fibrillation (AF), a common heart rhythm problem. Overall, higher genetically predicted BMI was linked to increased AF risk. When we partitioned the BMI genetic instruments by pathway, the link to AF was predominantly driven by SNPs in the “metabolic” pathway group, compared to the “mental health” group. This finding aligned nicely with previous tissue-partitioned studies (which we replicated here) that showed the link between BMI and AF was mainly driven by SNPs linked to “brain” tissue, more so than “adipose” tissue. This suggests that the metabolic *pathway* and the brain *tissue* might be key players in how BMI influences AF risk.

Why This Matters (And What Comes Next)

So, what’s the big takeaway from all this partitioning? It’s not enough to just say “BP affects your heart” or “BMI affects your heart.” These traits are influenced by a multitude of genetic factors, and those factors work through distinct biological routes – whether we define those routes by the biological *system* they affect (pathway) or the *tissue* where their effects originate.

Our study shows that these two ways of looking at the genetic influences – pathway-partitioned and tissue-partitioned – often give us complementary insights. Sometimes they agree (like the vascular/artery link for BP and T2D), and sometimes they highlight different aspects (like the vessel pathway vs. nephro tissue for BP and CHD). This difference is super interesting because it reflects the different biological information captured by each method: one looks at the overall symptomatic effect on a system (like kidney disease), the other looks at where the gene is active (like kidney tissue).

It’s important to remember that interpreting these partitioned effects requires caution. We need to be confident that our grouping methods are actually capturing distinct biology. That’s why our sensitivity analyses, like the random SNP sampling, are crucial. They help us show that the differences we see are unlikely to be just random chance.

This work isn’t without its challenges, of course. Grouping SNPs by Mendelian disease pathways sometimes involves manual curation and can be ambiguous if a gene is linked to multiple diseases. The tissue approach relies on gene expression data (eQTLs), which can also have limitations, like genes being co-expressed in many tissues. Also, combining multiple partitioned groups in multivariable MR can be tricky and requires enough statistical power.

But the potential here is huge! As we get more detailed biological data – like information from single cells or protein interactions – we can refine these methods even further. Imagine being able to pinpoint exactly which cell types or molecular mechanisms are driving the effect of a complex trait on a disease. This kind of detailed understanding is key for developing more targeted and effective treatments.

In a nutshell, this study introduces a cool new way to use Mendelian disease information to understand the genetic architecture of complex traits like BP and BMI. By comparing it with the tissue-based approach, we get a richer, more nuanced picture of how these traits contribute to heart disease and other outcomes. It’s a reminder that the genetic story of health is told not just by individual genes, but by the intricate biological pathways and tissues they operate within.

Ultimately, approaches like these help us move beyond broad associations to uncover the specific biological levers we might need to pull to improve health. It’s exciting stuff!

Source: Springer