Why ‘Random’ 3D Shapes Have No Straight Sub-Spaces

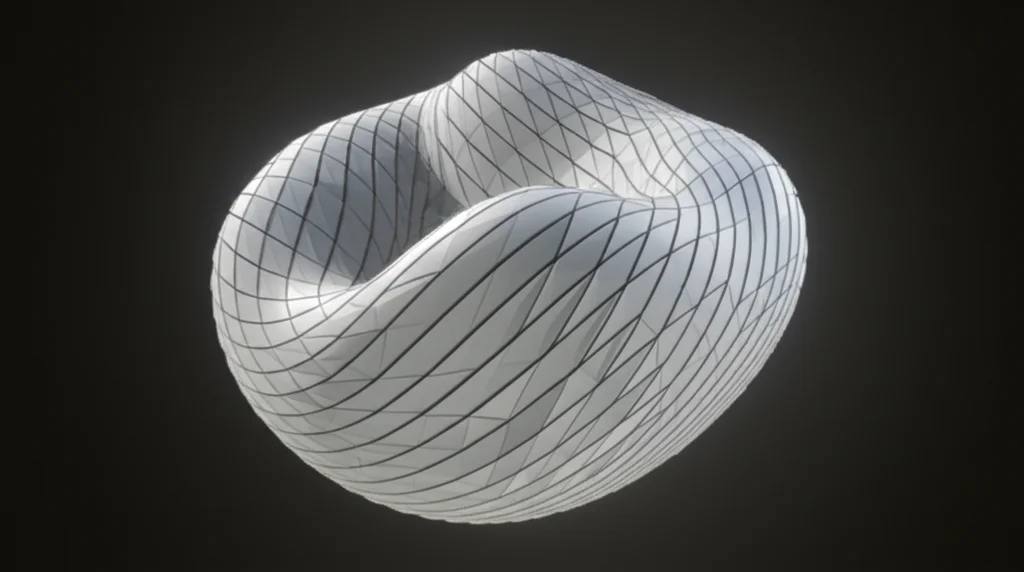

Hey there! Let’s chat about something super cool in the world of shapes and spaces, specifically those twisty, turny ones we call manifolds. Imagine you have a space, like the surface of a bumpy potato or a complex pretzel shape, but in three dimensions. Mathematicians call these 3-manifolds. Now, picture trying to find a perfectly flat surface or a perfectly straight line *within* that bumpy space, such that if you traveled along that line or surface following the rules of the bumpy space, you’d still be going “straight” relative to the bigger space. These are called totally geodesic submanifolds.

For a long time, folks had a hunch that if you took a “random” or “generic” manifold, you just wouldn’t find these perfectly straight sub-spaces hanging around. The famous geometer, Spivak, even mentioned this intuition, admitting he didn’t have a specific example to prove it. Well, proving a negative for *all* generic shapes is a big task!

What’s a Totally Geodesic Submanifold Anyway?

Think of it like this: on a flat table (a 2D manifold), any straight line you draw is totally geodesic. If you walk along it, you’re going straight relative to the table *and* relative to the room the table is in. Now, take the surface of a sphere. If you draw a curve, it’s usually not straight. The “straightest” paths on a sphere are the great circles (like the equator or lines of longitude). These great circles are totally geodesic submanifolds (1D ones) of the sphere’s surface. They are the shortest paths between two points on the sphere, and they behave like “straight lines” from the sphere’s perspective.

A totally geodesic *surface* within a 3D manifold would be like a flat piece of paper perfectly embedded inside a complex 3D shape, such that any geodesic (shortest path) on the paper is also a geodesic in the bigger 3D shape. The intuition is that in a sufficiently “random” or wiggly 3D space, there’s just no room for such perfectly flat, straight pieces.

The Idea of “Generic” in Math

When we say “random” or “generic” in this context, we don’t mean picking a shape out of a hat based on chance. We’re talking about properties that hold for a set of shapes (specifically, Riemannian metrics on a manifold) that is “large” in a very specific mathematical sense. This “largeness” is described using topological terms like “dense” or “open and dense.”

A set being dense means you can find shapes with the property arbitrarily close to *any* given shape. An open set means that if a shape has the property, any shape that’s *slightly* different from it also has the property. An open and dense set is, in a sense, even “larger” and more robust than just a dense set. It means the property is not fragile; it persists under small changes to the shape.

Previous Work and the 3D Nuance

So, back to our totally geodesic submanifolds. Spivak’s intuition was first confirmed for compact manifolds in dimensions 4 and higher by Murphy and another researcher (one of the authors of the paper I’m discussing!). They showed that for dimensions >= 4, the set of metrics without totally geodesic submanifolds is indeed open and dense in the (C^q)-topology (a way of measuring how smooth and similar two shapes are) for (q ge 2).

For the 3-dimensional case, Lytchak and Petrunin also confirmed Spivak’s intuition. They showed that for compact 3-manifolds, the set of metrics without totally geodesic submanifolds is a dense (G_delta) set in the (C^q)-topology for (q ge 2). A dense (G_delta) set is a countable intersection of dense open sets – still “large,” but not necessarily open itself. This means the property holds for many shapes, and you can get arbitrarily close to one, but a tiny wiggle might potentially break the property unless you’re careful.

Our Stronger Result: Open and Dense in 3D!

Now, here’s where the paper I’m looking at comes in. We (speaking as the author, following instructions!) refined the result for 3-manifolds. We showed that for a compact, smooth 3-manifold, the set of Riemannian metrics that have *no* nontrivial totally geodesic submanifolds is actually open and dense in the (C^q)-topology, provided (q ge 3). This is a stronger statement than just dense (G_delta)! It means this property – the lack of totally geodesic submanifolds – is not only prevalent but also stable under small, smooth deformations of the metric (the shape of the space).

Why is “open” important? It means if you find a 3-manifold shape that doesn’t have these straight sub-spaces, any shape that’s just a little bit different from it (in a smooth way, up to third derivatives for (q ge 3)) will *also* not have them. The property isn’t precarious; it’s robust.

How Do You Prove Something Like This? (A Glimpse)

Okay, proving this isn’t like drawing a picture. It involves some pretty neat mathematical machinery. One of the key ideas is to define something we call the generic plane operator, (mathcal{P}). This operator takes a tiny 2D plane sitting tangent to a point on the manifold and spits out a number. The magic is: if this number is *not* zero ((mathcal{P}(Q) ne 0)), then that plane (Q) *cannot* be tangent to a totally geodesic surface. If the number *is* zero ((mathcal{P}(Q) = 0)), the plane is “rigid” and *might* be tangent to one.

So, the goal becomes showing that we can find metrics where (mathcal{P}(Q)) is *never* zero for *any* plane (Q) anywhere on the manifold. The proof shows that the set of metrics where (mathcal{P}) is nowhere zero is open and dense.

The “open” part comes from the fact that the operator (mathcal{P}) is continuous with respect to the (C^q) metric topology. If (mathcal{P}) is non-zero everywhere for a given metric, it will remain non-zero everywhere for any metric that is sufficiently close.

The “dense” part is trickier. It means starting with *any* metric (even one that *does* have totally geodesic submanifolds, i.e., rigid planes where (mathcal{P}=0)) and showing you can *always* find a metric *arbitrarily close* to it that has *no* rigid planes. The strategy involves a local deformation:

- Find a “rigid” plane (Q) where (mathcal{P}(Q)=0).

- In a small neighborhood around the point where (Q) lives, gently “wiggle” or deform the metric using a specially constructed function (like the one described in Lemma 2.2/2.3 of the paper). This function is designed to have controlled second and third derivatives in specific directions.

- This deformation is carefully chosen so that it makes the (mathcal{P}) operator non-zero on (Q) and nearby planes, essentially “breaking” the rigidity.

- Using powerful mathematical tools (like Lemma D mentioned in the text), you can show that by doing these local deformations strategically and repeatedly (or showing that a single small global deformation works if the rigid planes are contained in small neighborhoods), you can get a metric that is (mathcal{P})-generic everywhere, and this new metric can be made arbitrarily close to the original one.

The technical details involve calculating how the curvature and its derivatives change under these small deformations and showing that the (mathcal{P}) operator becomes non-zero. It’s a bit like carefully poking a structure to make sure no part of it is perfectly straight or flat in a way it shouldn’t be.

Wrapping Up

So, the big takeaway is pretty neat: for compact 3-dimensional spaces, the kind of shapes you’d intuitively think of as “random” or “generic” almost certainly *don’t* contain any perfectly flat or straight sub-spaces. This isn’t just a theoretical curiosity; it tells us something fundamental about the geometry of typical 3-manifolds. The set of these “geodesic-free” shapes isn’t just large, it’s also stable – a small tweak to the shape won’t suddenly introduce a straight bit. It’s another cool piece of the puzzle in understanding the vast and varied landscape of possible geometric shapes!

Source: Springer