Your Kidney’s Secret Shield: How Your Body’s Own Galectin-8 Fights Damage

Hey There, Let’s Talk Kidneys!

So, imagine your kidneys, these amazing little filters working tirelessly for you. Sometimes, though, they hit a rough patch – maybe from an infection, a nasty toxin, or just not getting enough blood flow for a bit. That’s what we call Acute Kidney Injury (AKI). It’s a serious deal, a sudden dip in how well they work. And the tricky part? Often, AKI doesn’t just clear up perfectly; it can lead to long-term scarring, or fibrosis, which can eventually lead to chronic kidney disease (CKD). Not exactly a happy thought, right?

For the longest time, we’ve been trying to figure out *why* some kidneys bounce back and others get stuck in this cycle of damage and scarring. What are the body’s own internal mechanisms doing? Are they helping, or sometimes, getting in the way?

Enter Galectin-8 (Gal-8). Now, this isn’t some newfangled drug; it’s a protein your body naturally makes. We know it’s involved in all sorts of things, like how cells grow, how they change shape (a process called epithelial-mesenchymal transition, or EMT), and crucially, how your immune system behaves. All these things are super important when a kidney is trying to heal after an injury.

We’d seen hints that *giving* extra Gal-8 (what we call exogenous Gal-8) seemed to protect kidneys in studies. That was exciting! But it left a big question hanging: what about the Gal-8 your body *already* has? What’s its natural job during AKI? Does it help prevent that slide towards fibrosis, or is it just… there?

Putting Endogenous Gal-8 to the Test

To get to the bottom of this, we did what scientists often do: we looked at mice. Specifically, we compared regular mice (let’s call them the ‘control crew’ or Lgals8+/+) with mice that were engineered to *not* make Gal-8 (the ‘Gal-8 missing team’ or Lgals8-/-). These special mice had a little trick: where the Gal-8 gene should be, they had a reporter gene that makes a blue color (β-galactosidase) when the Gal-8 gene *would* have been active. This let us see where Gal-8 is normally expressed.

We gave both groups of mice a substance called folic acid (FA), which is a known way to cause AKI in mice. It’s a well-established model that lets us look at two distinct phases:

- The Acute Phase: The first couple of days, when the injury is fresh and the kidney is in crisis mode.

- The Fibrotic Phase: About two weeks later, when the kidney is either recovering nicely or starting down that path towards scarring.

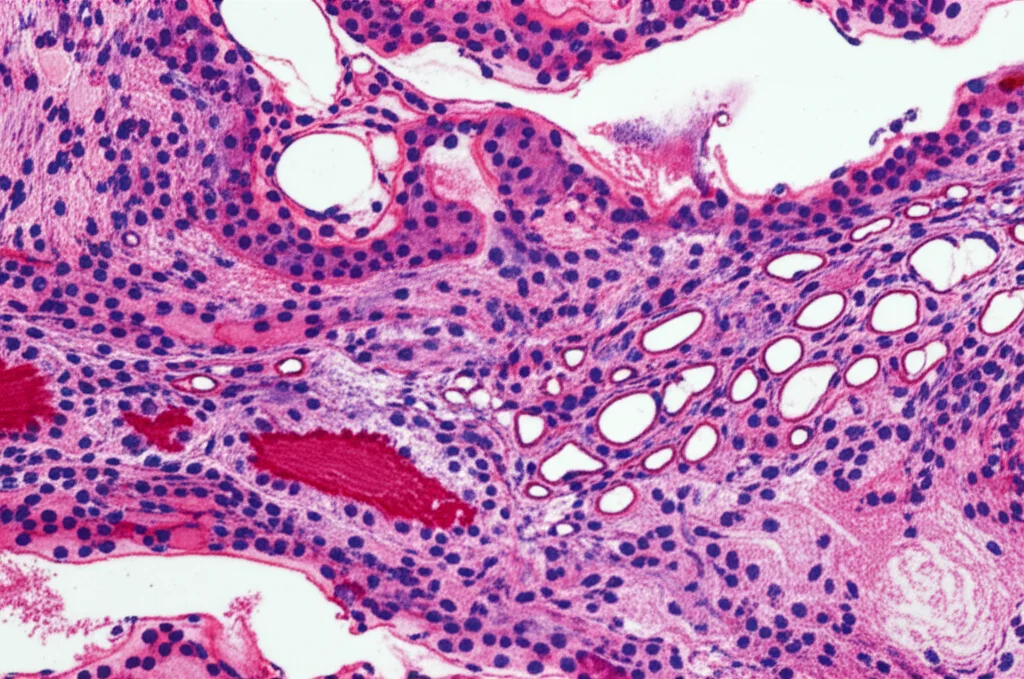

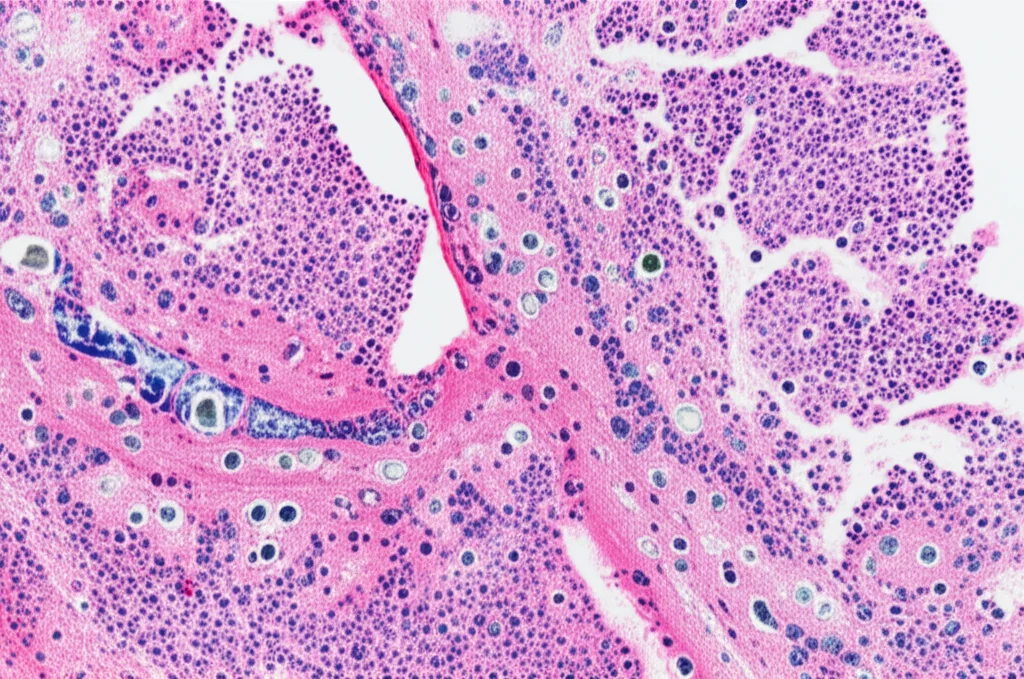

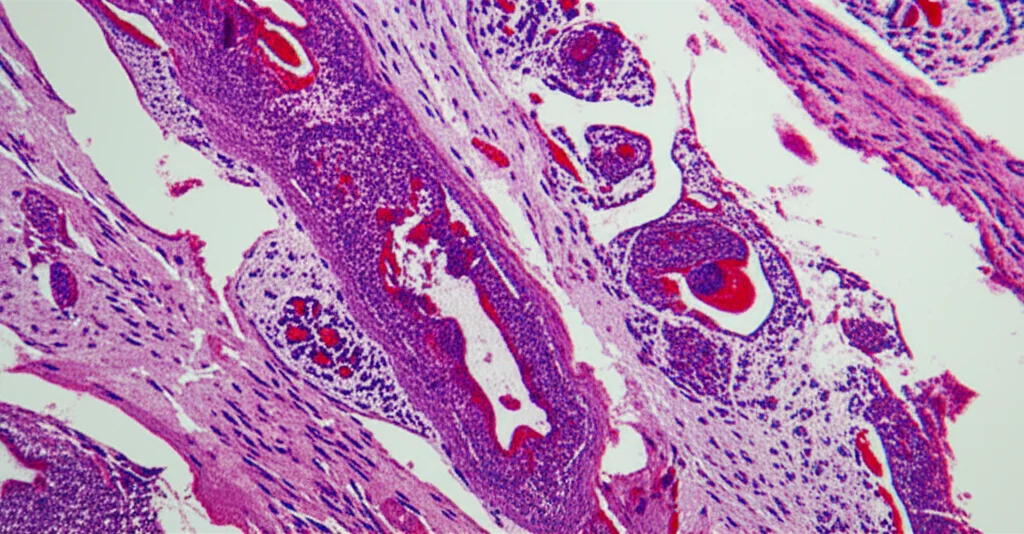

We checked a bunch of things at both time points: how well the kidneys were working (measuring stuff like creatinine in the blood), what the kidney tissue looked like under the microscope (looking for damage, inflammation, and scarring), and what the immune cells were up to.

Gal-8’s Kidney Hideout and What Happens After Injury

First off, where does Gal-8 hang out in a healthy kidney? Using our special Gal-8 missing mice and looking for that blue color, we found Gal-8 is mostly in the outer part of the kidney, the cortex. It was chilling in the tubules (the tiny tubes that filter waste), the glomeruli (the filtering units), and even the blood vessels. Pretty widespread in the key working parts!

Now, the big question: what happens to Gal-8 levels when the kidney gets hurt by that folic acid? Turns out, its levels dropped significantly – by about half – and stayed low through both the acute and fibrotic phases. This is interesting because it suggests the kidney’s natural supply of this potentially helpful protein goes down right when you might need it most.

The Early Days: A Bit of a Puzzle

In the immediate aftermath (the acute phase, day 2), both the regular mice and the Gal-8 missing mice showed similar signs of kidney trouble. Their kidney function dropped, and the tissue looked damaged under the microscope – tubules were swollen, flattened, and clogged up. Surprisingly, the regular mice (with Gal-8) actually showed slightly *more* tubular dilation and higher levels of certain injury markers like NGAL compared to the mice without Gal-8. This was a bit counterintuitive, given that exogenous Gal-8 seemed protective. It suggests that maybe the *acute drop* in Gal-8 in the regular mice is problematic, or perhaps the mice *missing* Gal-8 from the start developed some compensatory mechanisms. Either way, endogenous Gal-8 didn’t seem to be a major player in preventing the *initial* damage or influencing the early stages of cell repair (like proliferation or cell death).

The Long Game: Where Gal-8 Shines

But here’s where the story really takes shape. Fast forward to the fibrotic phase (day 14). The mice missing Gal-8 started looking significantly worse. Their kidneys showed much more widespread structural damage in the cortex. And critically, they had way more fibrosis – that nasty scarring characterized by excessive collagen deposition. The regular mice, with their endogenous Gal-8 (even though it was reduced), had significantly less scarring. This strongly suggests that your body’s own Gal-8 is crucial for preventing that maladaptive repair process that leads to long-term fibrosis after AKI.

We also looked at the cells primarily responsible for laying down all that scar tissue: myofibroblasts. These are activated fibroblasts that produce a lot of extracellular matrix proteins like collagen. We checked markers of fibroblast activation (like alpha-SMA and vimentin) and found that the levels were pretty similar between the two groups of mice at day 14. This was another interesting piece of the puzzle – the *increased fibrosis* in the Gal-8 missing mice wasn’t simply because they had more activated fibroblasts.

The Immune Connection: Keeping the Peace

If it wasn’t just about fibroblasts, what else could explain the difference in fibrosis? Ah, the immune system! We know inflammation plays a huge role in driving fibrosis. We looked at different types of immune cells infiltrating the kidney.

And bam! Here was a major finding: the mice missing Gal-8 had a dramatic increase in the infiltration of certain types of T cells, particularly Th17 cells and Tc17 cells. These are specific kinds of immune cells known for producing a pro-inflammatory molecule called IL-17, which is strongly linked to tissue damage and fibrosis in the kidney and elsewhere. In the regular mice (with Gal-8), even though they had AKI, the infiltration of these particular cells was much lower.

This is a big deal! It seems that one of the key ways endogenous Gal-8 protects the kidney from fibrosis is by acting as a sort of ‘peacekeeper’ or ‘bouncer’ for the immune system, specifically by limiting the number of these pro-fibrotic Th17 and Tc17 cells that hang around and cause trouble during the repair phase. It helps resolve the inflammation instead of letting it fester and drive scarring.

Putting It All Together

So, what’s the takeaway from all this? It looks like your body’s own Galectin-8, while perhaps not a frontline defender against the *initial* hit of AKI, is absolutely crucial for the *long-term* outcome. It helps prevent the kidney from going down the path of maladaptive repair and fibrosis. It does this, at least in part, by keeping a lid on the inflammatory response, particularly by limiting the infiltration of those pesky Th17 and Tc17 cells that fuel scarring.

This research really highlights the importance of endogenous Gal-8 in maintaining kidney health after injury. It’s not just about external treatments; our own bodies have protective mechanisms at play.

What This Could Mean for You and Me

Understanding this natural protective role of Gal-8 opens up exciting possibilities. Could we develop therapies that boost your body’s own Gal-8 levels after AKI? Or perhaps target those Th17 cells more effectively? This study adds another piece to the complex puzzle of kidney repair and fibrosis.

It also raises interesting questions about why Gal-8 levels drop after AKI. And could problems with Gal-8, perhaps due to certain diseases or even autoantibodies against it (which have been found in conditions like sepsis, lupus, and rheumatoid arthritis), make someone more vulnerable to developing fibrosis after AKI? Sepsis, for example, is a major cause of AKI, and if sepsis patients also develop antibodies that block their own Gal-8, that could be a double whammy for their kidneys.

Monitoring Gal-8 levels or even these autoantibodies in patients who’ve had AKI, especially those at high risk like sepsis patients, might help us predict who is more likely to develop CKD and who might benefit most from potential future therapies aimed at boosting Gal-8’s protective effects.

The Bottom Line

In a nutshell, this study gives us compelling evidence that your body’s own Galectin-8 is a vital player in preventing the long-term consequences of acute kidney injury. It acts as a guardian against fibrosis by keeping certain pro-inflammatory immune cells in check. It’s a reminder that sometimes, the best protection comes from within!

Source: Springer