Seeing Force: How We Zapped Parallax with Moiré and Fiber Optics!

Alright, let’s talk about force. Not like, “May the force be with you” force, but the kind you feel when you grab something, push something, or when a robot arm interacts with the world. You know, the nitty-gritty physical contact stuff. Understanding these forces is super important, especially when you’re doing delicate work, like surgery with a robot (yeah, that’s a thing!).

See, when a robot or any automated device is doing a job, it’s constantly bumping into things, applying pressure. If the person controlling it can’t *feel* that force, things can go wrong. We’ve seen studies showing that without good force feedback, operators tend to push harder than they need to, which can cause damage. So, getting that force info back to the human is a really big deal.

The Usual Suspects: Traditional Force Sensors

Now, the traditional way to measure force involves a bunch of electrical bits and bobs. Think strain gauges, amplifiers, wires, computers, monitors – the whole nine yards. You apply force, a sensor measures a tiny deformation, converts it into an electrical signal, sends it down a wire, processes it on a computer, and maybe shows you a number or a graph.

There are some pretty cool systems out there already. We’ve seen haptic gloves that let you feel what the robot feels, wearable devices that give fingertip feedback, and even systems integrated into surgical tools that reproduce touch sensations. These are fantastic for detecting small forces and giving detailed feedback.

But here’s the catch: they often use all those electrical components. The force data has to travel from the sensor to a computer and then to the operator. While reproducing the force for the operator is doable, the whole setup can get complicated and, let’s be honest, quite expensive. We thought, “There’s got to be a simpler way, right?”

Enter Moiré Patterns: A Visual Trick

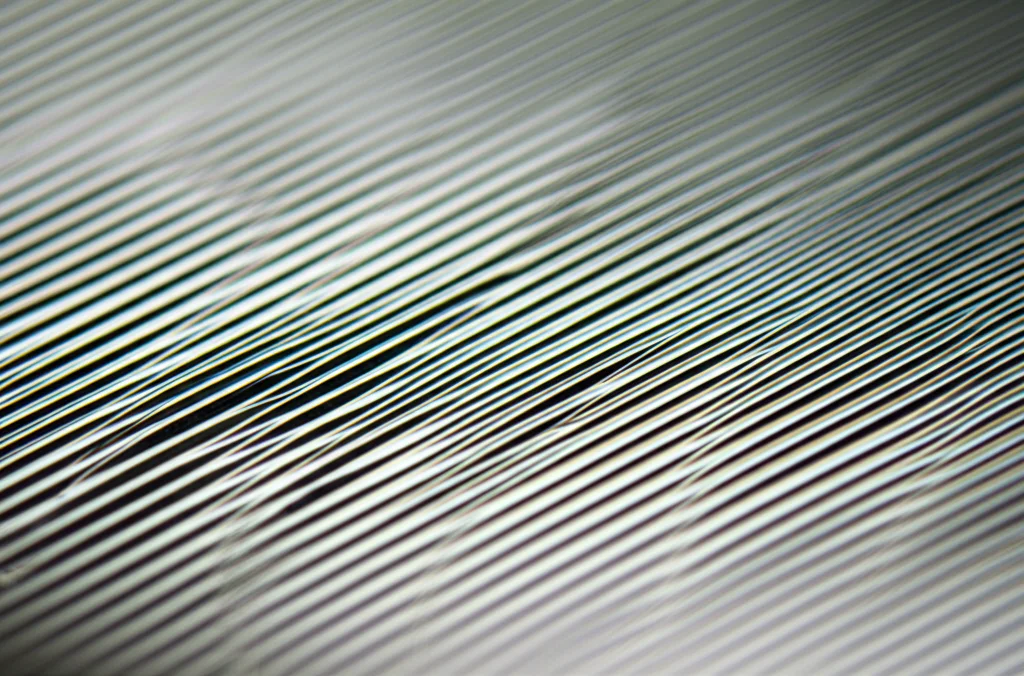

So, we started thinking about Moiré patterns. Ever seen those cool wavy or striped patterns that appear when you overlap two screens or fabrics with similar patterns? That’s Moiré! It happens when two patterns with regular intervals are put on top of each other, and they create a *new* pattern of fringes. The really neat thing about Moiré patterns is that they can make tiny movements look much, much bigger. It’s like a built-in visual amplifier!

People have used Moiré fringes for all sorts of clever things, like measuring tiny displacements, analyzing 3D shapes, and even in sensors. We’ve tinkered with combining Moiré patterns with things like surgical forceps before, using stripes or characters to show how much force was being applied.

The big win with this Moiré approach? No electrical components needed! No strain gauges, no amplifiers, no cables transmitting power or data. The system configuration is super simple – no monitors or computers required just to *see* the force. Plus, because the force is visualized directly, anyone looking at the robot can intuitively grasp the force being applied. It’s easy to share that information among a team. And yes, you *can* still get numerical data by taking a picture with a camera and doing some image processing later, which is great for documenting the work.

The Hiccups: Hysteresis and Parallax

Now, our earlier Moiré force visualization attempts, while simple and electrical-free, ran into a couple of annoying problems.

First, if the two patterns (we call them gratings) that create the Moiré effect were in contact, you’d get friction. When you apply force and then release it, the friction means the pattern might not go back exactly where it started. This is called hysteresis, and it’s a big no-no for accurate sensors. You want the reading to be the same every time you apply the same force, regardless of whether you got there by increasing or decreasing the load.

Okay, so if touching causes friction, why not just put a small gap between the gratings? Good idea! No contact, no friction, no hysteresis. Problem solved… almost.

Introducing a gap brought up the second, even more frustrating problem: parallax. You know how if you look at something from different angles, its position relative to the background seems to shift? That’s parallax. With a gap between the gratings, the Moiré pattern you see would change depending on where you were standing or looking from. The displayed force would look different depending on your viewing angle, even if the actual force was the same. This makes accurate measurement impossible. Eliminating parallax became absolutely essential.

People have come up with ways to tackle parallax before, like complex alignment methods or motion compensation in displays. But these often make the system structure way more complicated, require specific usage conditions, add more moving parts, and cost a bundle. We needed something simpler, something that kept the elegant simplicity of the Moiré idea but killed the parallax issue dead.

Our Solution: Fiber Optic Plates and Diffuse Reflection

So, we put our heads together and came up with a method using a Fiber Optic Plate (FOP) and diffuse reflection. The goal was to let the operator see the force visualization clearly and accurately, *without* any parallax, from pretty much any angle. And we wanted to keep the structure simple and compact, still avoiding all those electrical components.

Let’s break down the magic ingredients:

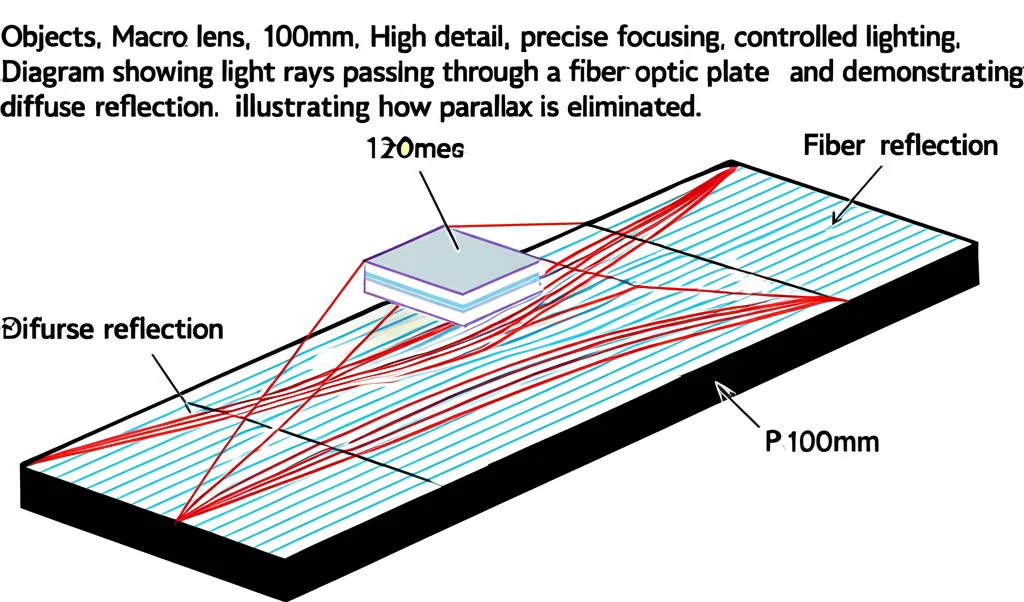

- Fiber Optic Plate (FOP): Imagine a thin plate packed *full* of tiny optical fibers, standing on end. Like a bundle of microscopic straws. Light entering one end of a fiber travels straight through it and comes out the other end. If you put an FOP on top of a pattern, that pattern basically appears on the *other* surface of the FOP. Crucially, because the light travels straight through the fibers, the image doesn’t shift when you look from different angles.

- Diffuse Reflection: Think of a matte surface, like plain paper. When light hits it, it scatters in all directions. Unlike a mirror (regular reflection) where the angle of reflection equals the angle of incidence, diffuse reflection bounces light everywhere. This is why you can see a matte surface clearly from many different angles.

We figured if we could combine these two concepts, we could make the image of one grating appear on the surface of the FOP right next to the other grating, effectively eliminating the gap *optically* while still having a physical gap to prevent friction.

Putting the Pieces Together

Here’s the setup we designed: We placed one Moiré grating (let’s call it Grating 1) on the bottom surface of the FOP. The other grating (Grating 2) was placed on the top surface of a diffuse reflecting plate. We put a small physical gap between Grating 1 (on the FOP) and Grating 2 (on the diffuse reflector).

Because of how the FOP works, Grating 1 effectively appears on the *top* surface of the FOP. And thanks to the diffuse reflection and the FOP, Grating 2 also appears on the *top* surface of the FOP, right next to Grating 1. The key is making that physical gap small enough. If the gap is tiny, the light rays coming from Grating 2 through the FOP are constrained enough that the image of Grating 2 appears as a single, clear line (or character) on the FOP’s top surface, and its position doesn’t change regardless of your viewing angle.

So, we have Grating 1 appearing on the FOP’s top surface (no parallax effect on it) and Grating 2 also appearing on the FOP’s top surface (no parallax effect on it, thanks to FOP + diffuse reflection + small gap). Since both gratings are effectively on the same plane (the FOP’s top surface) from the observer’s perspective, the Moiré fringe they create doesn’t shift with the viewing angle. Bingo! Parallax eliminated. And because there’s a physical gap, no friction, no hysteresis. We think this innovation really nails the problems we saw before.

Getting Numerical Data from Images

While the visual display is great for intuitive understanding, sometimes you need a precise number. We also developed a method to calculate the exact force magnitude by taking a photo of the Moiré pattern and analyzing the image.

Basically, we capture the image, isolate the Moiré fringe area, and look at the intensity (brightness) profile across the pattern. When force is applied, the Moiré fringe shifts. By comparing the intensity profile of the shifted pattern to the profile when no force is applied, we can calculate exactly how much the pattern moved in the image. Since we know the magnification factor of the Moiré pattern and the physical properties of the mechanism (like the spring stiffness), we can use that measured shift to calculate the applied force. It’s pretty neat – you get the instant visual feedback, and you can also get hard numbers if you need them.

Putting It to the Test!

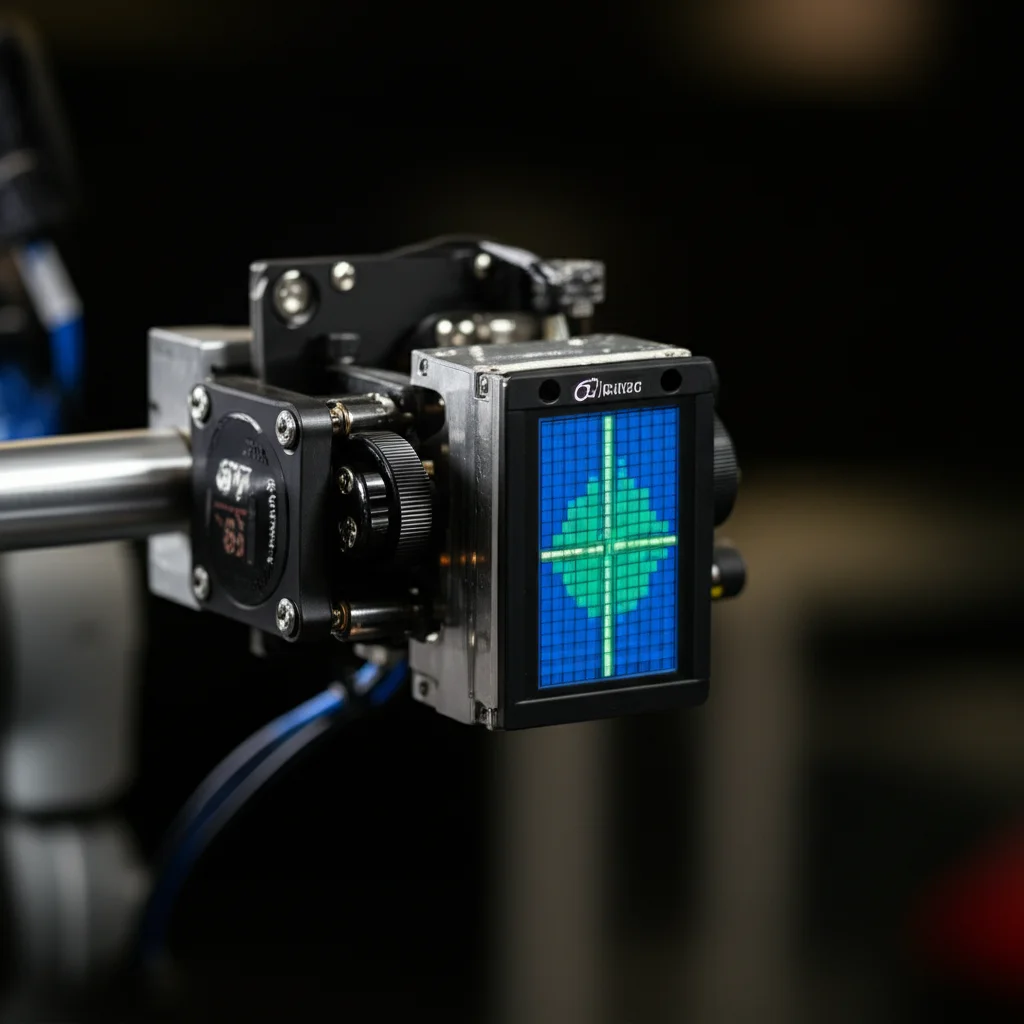

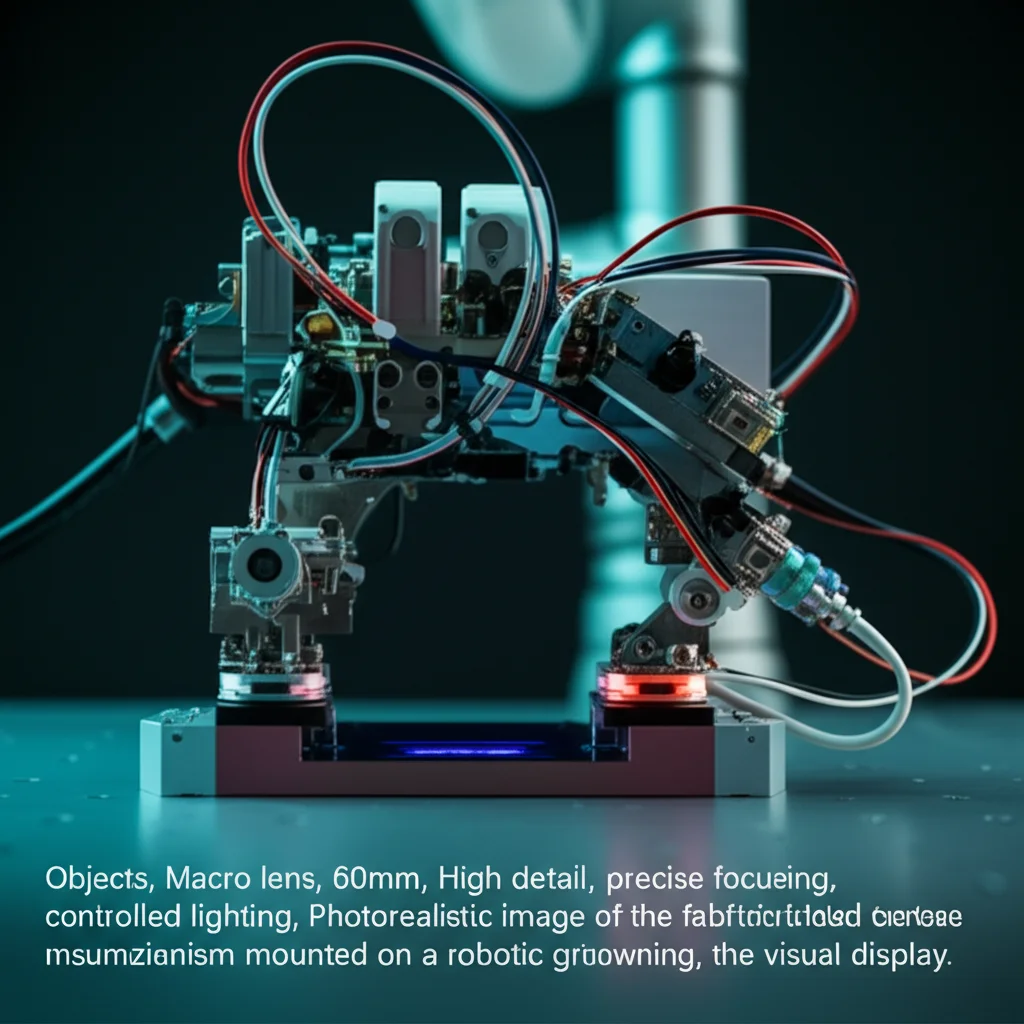

Of course, proposing a cool idea is one thing; proving it works is another! We built a prototype of our force visualization mechanism. It’s got the parallel spring structure to ensure displacement happens without unwanted rotation, the gratings, the FOP, and the diffuse reflector with that tiny gap. We used brass for the flexible part and set up the gratings to display either stripe patterns or characters corresponding to different force levels.

We mounted our mechanism onto a parallel gripper – you know, like a simple robotic hand that grabs things. The mechanism sits between one of the jaws and the base, so when the gripper closes and applies force, our mechanism visualizes that gripping force.

First, we wanted to see if the character display worked. We applied different forces and, bam! The mechanism successfully displayed characters “1” through “5” as the force increased, just like we designed. It clearly showed the approximate force level visually.

Next, we tackled the hysteresis problem. We tested the mechanism with the gratings in contact (where we expected friction) and with the small gap (where we expected no friction). Using image processing to get precise force readings, the results were clear: when the gratings touched, we saw significant hysteresis – the force reading was different depending on whether we were increasing or decreasing the load. But with the gap, the readings matched a standard force sensor almost perfectly, whether increasing or decreasing the force. Hysteresis? Eliminated!

Finally, the big one: parallax. We compared our FOP-based mechanism to a similar one using a standard acrylic plate (like our earlier attempts) instead of the FOP, both with a small gap. We observed both mechanisms from different angles, up to 30 degrees off-center, without applying any force (so it should show ‘zero’ or ‘1’).

With the acrylic plate, the Moiré pattern shifted dramatically as we changed our viewing angle. What looked like “1” from straight on might look like “5” from the side! This confirmed the parallax problem was a major issue with the simple gap method.

But with our FOP mechanism? The Moiré pattern stayed put! It showed “1” consistently, no matter the viewing angle. We even did image processing on the images taken from different angles to quantify the error. The acrylic plate version showed force errors climbing up to 24 Newtons at a 30-degree angle. Our FOP version? The force error stayed right around 0 Newtons, with only minor fluctuations. Parallax? Eliminated!

Wrapping It Up

So, there you have it! We’ve proposed and demonstrated a pretty cool mechanism for visualizing force. By introducing a gap between the Moiré gratings, we got rid of the friction and hysteresis issues that plagued earlier contact-based designs. And by integrating a Fiber Optic Plate and using diffuse reflection, we successfully tackled the parallax problem that came with the gap.

The mechanism is simple, doesn’t need any electrical components for the visual display, provides intuitive force information, and allows for precise numerical measurement via image processing. Our experiments confirmed that it effectively displays force characters, eliminates hysteresis, and crucially, eliminates parallax errors, giving you a consistent, accurate view of the force no matter where you’re looking from. We think this opens up some exciting possibilities for simpler, more robust force sensing in various applications, especially where electrical sensors might be impractical.

Source: Springer