Zap! Turning Flue Gas CO2 into Valuable Chemicals with a Clever Coating

Hey there! Let’s chat about something pretty cool that could seriously shake things up in the fight against climate change. We all know CO2 is a big deal, right? And figuring out how to use it instead of just letting it build up is a massive challenge. One promising idea is called electrocatalytic CO2 reduction (CO2R), basically using electricity to turn CO2 into useful stuff like fuels and chemicals. Think of it as giving CO2 a second life!

Now, most of the work in this area has focused on using super pure CO2 gas. But here’s the catch: where does most of the CO2 we *actually* emit come from? Things like power plants and factories – what we call flue gas. And that stuff is *diluted*, usually only about 15% CO2, mixed with other gases like nitrogen. Cleaning that up to get pure CO2 is expensive and uses a ton of energy. So, the dream is to skip that whole purification step and use the diluted stuff directly.

But trying to zap diluted CO2 directly into valuable products, especially the complex ones with two or more carbon atoms (we call these C2+ products, like ethylene, ethanol, and acetate), has been a real headache. Why? Because when the CO2 is diluted, there’s less of it around the catalyst surface. This means another reaction, the hydrogen evolution reaction (HER) – basically just making hydrogen from water – becomes the easiest thing to do. And while hydrogen is useful, it’s not the valuable C2+ products we’re after, and it wastes energy and CO2.

Adding another layer of difficulty, most successful CO2R to C2+ happens in alkaline or neutral solutions. This helps activate the CO2 and link carbon atoms together, *and* it helps suppress that pesky HER. Sounds good, right? Well, not entirely. In these conditions, the CO2 loves reacting with the solution itself, forming carbonates and bicarbonates. This means a lot of your precious CO2 feedstock gets “lost” in the solution, leading to really low “single-pass carbon efficiency” (SPCE) – basically, how much of the CO2 you feed in actually ends up in your desired product in one go. Getting that lost CO2 back is another energy sink.

Using acidic solutions could fix the carbon loss problem, as CO2 doesn’t react with the acid like it does with bases. But remember that HER issue? It’s *even worse* in acid because there are tons of protons available to make hydrogen. So, finding a way to do CO2R to C2+ efficiently in acid, *especially* with diluted CO2, has been a major hurdle. Until now, mostly pure CO2 was used even in acidic systems to try and boost the CO2 concentration near the catalyst.

The Clever Coating Idea

So, what’s the breakthrough here? Imagine your catalyst surface is like a busy street. With diluted CO2, there aren’t many CO2 molecules around, and the street is full of protons (the stuff that makes acid acidic) just waiting to turn into hydrogen. The idea was: what if we could put something on the catalyst surface that acts like a magnet for CO2, pulling it in and concentrating it right where the action happens? And at the same time, what if this something could also act like a bouncer, keeping those protons away?

That’s exactly what these clever folks did! They came up with a simple yet brilliant strategy: coating a copper catalyst with a special material called an imidazolium-based anion-exchange ionomer. Think of this ionomer like a sticky, slightly water-repellent net that loves CO2.

How Does This Magic Coating Work?

The ionomer they chose is called Sustainion, which is commercially available. It has these imidazolium groups that are really good at grabbing onto CO2 molecules. So, even if the CO2 is diluted in the bulk gas, this coating pulls it in, creating a much higher concentration right at the catalyst surface. It’s like having a VIP lounge for CO2!

They did some neat experiments to show this. They put the coating on a flat surface and bubbled CO2. While the bare surface showed no bubbles sticking, the coated surface captured tons of them. They even measured the “stickiness” – the coated surface had about three times the CO2 adhesive force! High-speed cameras showed that CO2 bubbles didn’t just stick; they spread out quickly on the coating, suggesting fast CO2 transport across the surface. This “superaerophilic” (super gas-loving) feature is key.

But what about keeping those protons away? The coating is also a bit hydrophobic (water-repellent). They measured the water contact angle, and it jumped from 54° on the bare surface to a whopping 122° with the coating. This hydrophobicity helps block the movement of protons from the acidic solution to the catalyst surface.

So, you’ve got this fantastic setup: the coating pulls in diluted CO2, concentrates it, helps it move quickly across the surface, *and* pushes protons away. This creates a perfect little microenvironment right at the catalyst surface – a rich “three-phase interface” (gas, liquid, catalyst solid) – where CO2 reduction can happen efficiently while HER is suppressed.

Building and Testing the Catalyst

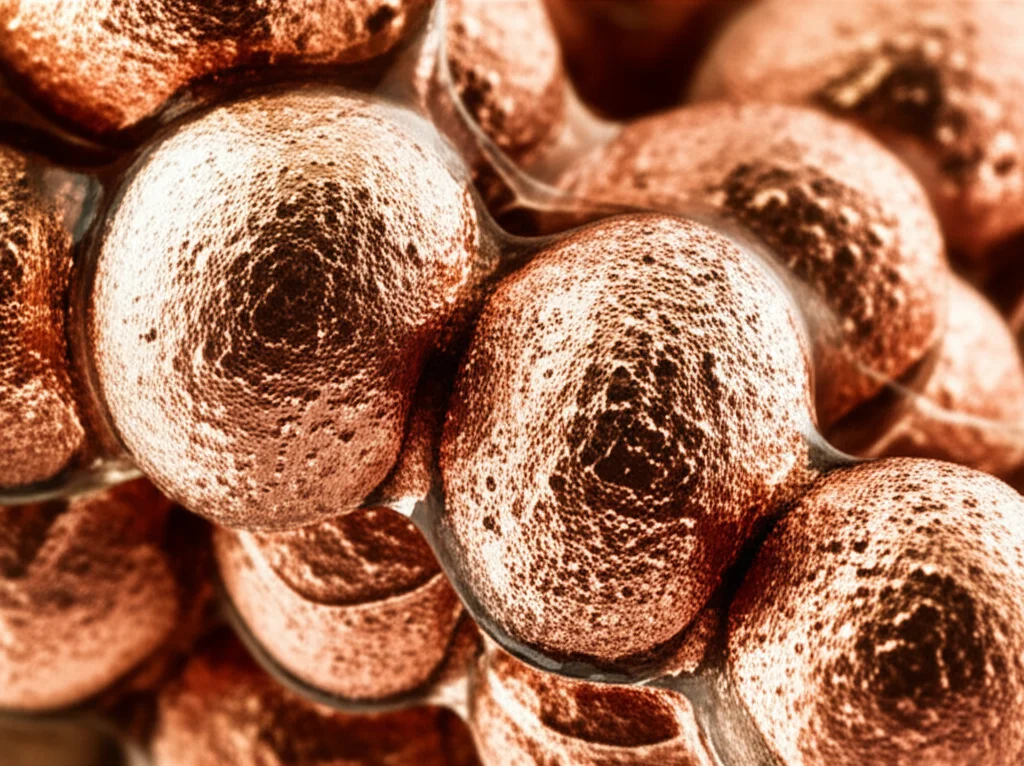

Okay, so the idea works on a flat surface. How about on an actual catalyst? They prepared copper nanoparticles and coated them with the Sustainion ionomer, creating what they call Cu@Sustainion. They checked it out with fancy microscopes (SEM, TEM) and other techniques (XRD, EDX, FTIR, XPS) to confirm the coating was there and didn’t mess up the copper structure too much. The coating was thin, about 10-30 nm thick.

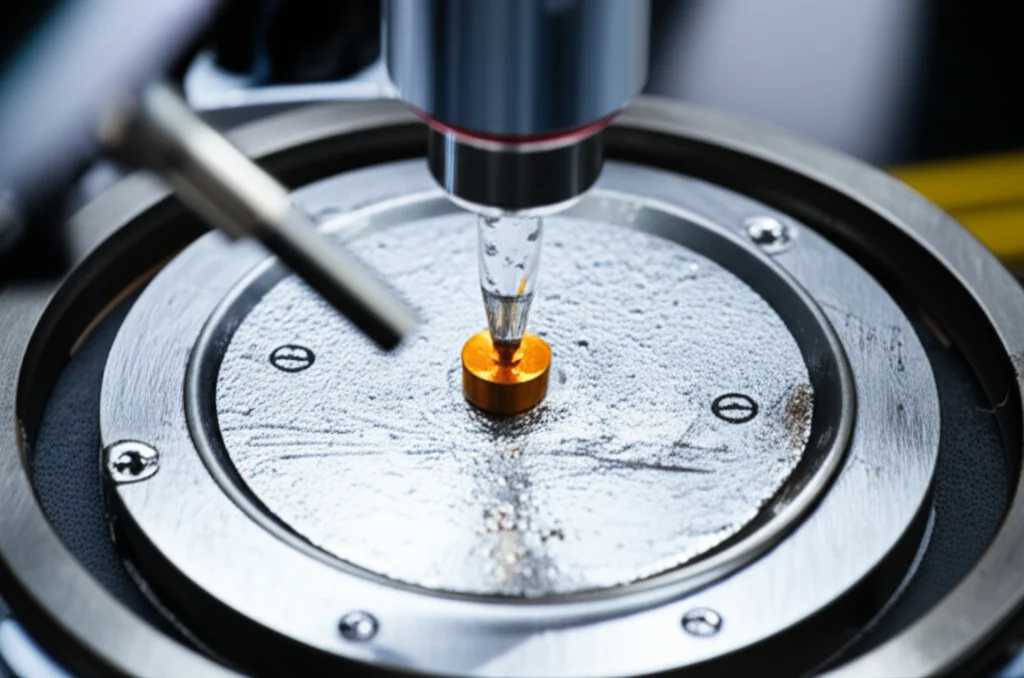

Then came the real test: putting it in an electrochemical flow cell, the kind of setup you’d use for this type of reaction. They used a strongly acidic solution (pH 0.8).

First, they tested it with *pure* CO2 to see if the coating helped even in ideal conditions. And boy, did it! At a high current density of 800 mA cm–2 (that’s a measure of how fast the reaction is going, and 800 is *really* fast for this kind of process), the Cu@Sustainion catalyst achieved a fantastic C2+ Faradaic efficiency (FE) of 78.2%. FE tells you what percentage of the electrical energy goes into making your desired product. For the bare copper catalyst at the same high current density, the C2+ FE was only 38.2%, and a lot of the energy went into making hydrogen (30.9% HER FE). The coating significantly boosted the desired C2+ products and squashed the unwanted hydrogen production.

They also checked the electrochemically active surface area (ECSA) and found the coated catalyst actually had a *smaller* active area. This is important because it means the improvement isn’t just because there’s more surface area working; the coating is making the existing surface *intrinsically* better at the right reaction.

They optimized the amount of coating and found a sweet spot (0.1 mg cm–2). They also showed that because they were working in acid, the carbon loss to carbonates was minimal, leading to high SPCEs, even with low CO2 flow rates. This is a big win compared to alkaline systems.

The catalyst was also pretty stable, running for 16 hours at a decent current density (500 mA cm–2) while maintaining high C2+ efficiency. And guess what? The coating strategy worked on other types of copper catalysts too, showing it’s a general approach.

Digging Deeper: Why It Works So Well

To really understand the magic, they did more tests. They measured the local CO2 concentration right at the catalyst surface using a clever electrochemical trick. They found that with the Sustainion coating, the local CO2 concentration was about *7 times higher* than on bare copper! This confirms the CO2 enrichment effect. Adsorption tests also showed the coated catalyst grabbed more CO2.

They figured out that both the hydrophobic part of the ionomer *and* the imidazolium cation itself play roles. The hydrophobic part helps concentrate the gas, while the imidazolium seems to have a chemical attraction to CO2, making the binding even stronger.

Then they looked at the proton blocking. Using a rotating disk electrode setup, they measured how easily protons could reach the catalyst surface. The coated catalyst showed a much lower “diffusion-limiting current” for HER, meaning the coating was indeed restricting proton transport. They calculated the kinetic current density for HER and found it dropped significantly after coating – clear evidence that the Sustainion layer acts as a barrier to protons.

They even peeked at the reaction intermediates using a technique called in-situ ATR-SEIRAS. They saw signals corresponding to *CO (carbon monoxide stuck to the surface), which is a key step in making C2+ products from CO2. The signal was much stronger on the coated catalyst, indicating more efficient CO2 activation. They also saw signals for *OCCOH, an intermediate formed when two carbon atoms link up – another crucial step for C2+ products. This signal appeared at a less negative (more favorable) voltage and was stronger on the coated catalyst, showing that the coating helps facilitate this carbon-carbon coupling step.

The Moment of Truth: Diluted CO2

Alright, all the previous tests were promising, but the real goal was using *diluted* CO2. They set up the flow cell again, but this time fed it a simulated flue gas mixture: 15% CO2 and 85% nitrogen, still in the strong acid (pH 0.8).

And here’s the really exciting part: the Cu@Sustainion catalyst performed almost as well with the diluted CO2 as it did with pure CO2! At 800 mA cm–2, it achieved a C2+ FE of 70.5% and a high SPCE of 73.6%. Compare that to the bare copper catalyst under the *same diluted CO2 conditions*, where the C2+ partial current density (how much C2+ product is actually being made) dropped drastically, retaining only 34% of its performance compared to pure CO2. The coated catalyst retained 90%!

This is huge! It means this catalyst and coating strategy can effectively work with CO2 concentrations similar to what you’d find in actual flue gas, without needing that expensive purification step. The high SPCE in acidic conditions also means you’re not losing a ton of CO2 to carbonate formation.

Wrapping It Up

So, what have we got here? A fantastic demonstration of how a simple coating of an imidazolium-based ionomer on a copper catalyst can overcome major challenges in CO2 electroreduction. By effectively concentrating diluted CO2 and simultaneously blocking unwanted hydrogen production, this catalyst can turn a weak stream of CO2 (like flue gas) into valuable multicarbon products with high efficiency, even in strongly acidic conditions.

This isn’t just a lab curiosity; it offers a really promising pathway towards directly converting industrial emissions into useful chemicals and fuels. It could make CO2 utilization much more energy- and carbon-efficient, bringing us closer to a carbon-neutral economy. Pretty neat, right?

Source: Springer