Living on Empty: The Hidden Burden of Fatigue in Young People with Sickle Cell Disease

Hey there! Let me tell you about something that really struck me after diving into some fascinating research. We often hear about the big, dramatic symptoms of conditions like Sickle Cell Disease (SCD), right? Pain crises, hospital stays… but what about the stuff that’s there *all the time*, quietly chipping away at life? This study I looked at shines a big, bright light on just that: fatigue in children and young people (CYP) with SCD. And honestly? It sounds absolutely exhausting, not just physically, but in every single way.

You see, fatigue isn’t just “feeling a bit tired.” For these young folks, it’s a massive, often invisible, challenge that messes with everything – school, friends, even just getting out of bed. This qualitative study, chatting with young people with SCD, their parents, and healthcare pros, really digs into what that feels like and what it means for their lives. It’s like getting a peek behind the curtain of what living with constant low energy truly entails.

A Constant State of Reduced Energy

Imagine waking up already feeling drained. That’s the baseline for many young people with SCD. They described it using some pretty vivid metaphors. One young person said, “It’s like having the appearance of a Land Rover but the energy capacity of a small Fiat.” Another felt like they were “going through life constantly on a low battery.” Oof.

They know it’s tied to their SCD – things like low haemoglobin or sickled red cells. It feels inescapable, like it’s just *part* of their fate. But it gets worse with things like not drinking enough, pushing themselves too hard (physically, mentally, even socially!), or dealing with pain crises. It brings exhaustion, dizziness, shortness of breath, and even trouble concentrating. It’s fascinating, and frankly, a bit scary, how closely linked fatigue and pain are for them – fatigue can be a trigger, a consequence, or even a warning sign of an upcoming pain crisis. This unpredictability makes planning anything a total gamble.

The Daily Struggle

Living with this kind of fatigue isn’t passive; it’s an active fight, every single day. Young people described it as a physical and mental ‘heaviness’. Think “having your bones replaced with lead” or “wearing a puffer coat filled with rocks” or even a “big grey cloud that sits over you.” Getting up in the morning requires immense effort. Staying awake and focused in school? A constant battle they often lose.

One young person put it powerfully: “With sickle cell anaemia, there’s the constant physical agony of fatigue we go through and getting up is difficult…not only is it a physical struggle, but it’s also a mental struggle… having to gain the strength to get up.” They felt like they were “in a war zone,” fighting against their own bodies just to participate in daily life. This isn’t like ‘normal’ tiredness that goes away with sleep; it’s always there. And while they push through, trying to maintain a sense of ‘normality’, they know they risk triggering a pain crisis. Fatigue, they said, always has the upper hand.

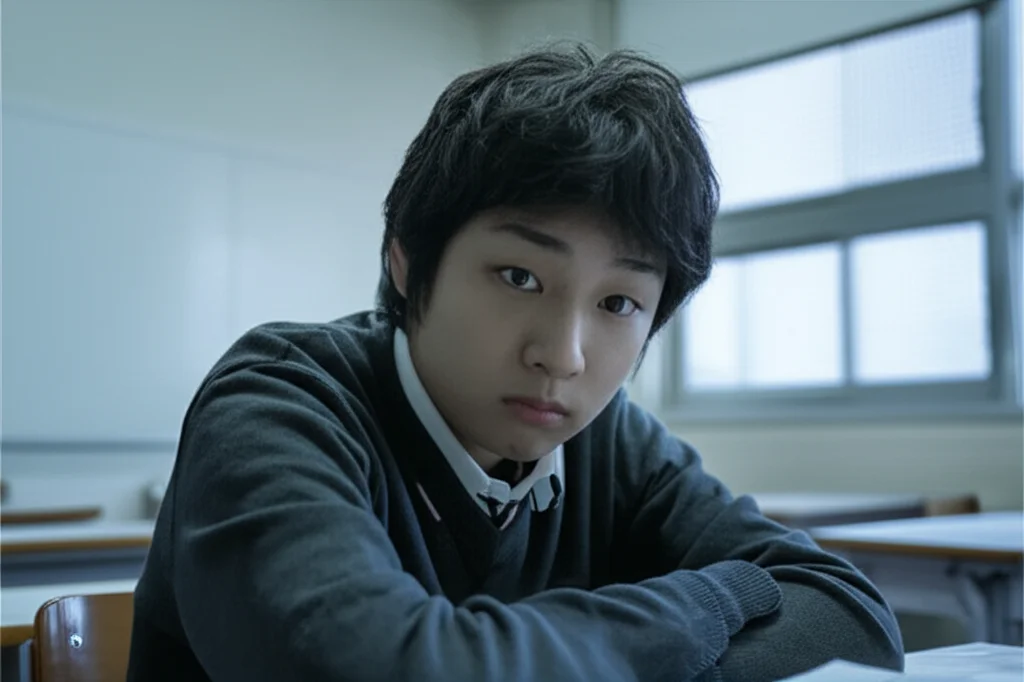

School is a major battleground. Frequent absences, struggling to keep up, even falling asleep in class – it all takes a toll on their education. It’s heartbreaking to hear a young person say they had to spend their whole summer catching up because fatigue made them fall behind. This constant, pervasive struggle has led many to just accept fatigue as ‘how it is’ with SCD.

The Invisibility of Fatigue

Here’s where it gets really tough. This constant battle, this profound exhaustion? It’s often completely invisible to others. Teachers, friends, even healthcare professionals sometimes miss it or misunderstand it. Young people felt immense pressure to hide their fatigue, to ‘push through’ and “hope no one sees” their struggle. They wanted to ‘pass’ as ‘healthy’ and ‘normal’.

But when they *did* try to explain, they were often met with disbelief. People would say, “Okay, so what have you done today?” and couldn’t grasp that simple activities required double the energy they had. This led to their experiences being discredited and, painfully, being labelled as lazy. To avoid this interrogation and stigma, many learned to just keep quiet and mask their fatigue, even though it made things harder. This need to conceal their struggle, while showing incredible resilience, also highlights the vulnerability and precarity fatigue creates.

Even in clinical settings, fatigue often goes unnoticed. Young people and parents said it wasn’t usually asked about in routine check-ups. Care seemed focused more on pain and complications. This made families feel like fatigue wasn’t important or, worse, was something they just had to cope with alone. Healthcare professionals admitted they felt unequipped to deal with it, lacking tools to measure it or clear pathways for support. Some even confessed they sometimes conflated SCD fatigue with ‘normal’ teenage tiredness or laziness.

But here’s a glimmer of hope: when fatigue *was* discussed, even without fancy assessments, it made a huge difference. It validated their experiences and made them feel seen. Young people had great suggestions for how healthcare providers could bring it up – asking about day-to-day life, school, and friendships often opens the door naturally. Simple questions like “What I’m able to do, what I’m not able to do and what I’ll like to do because of my tiredness?” could make a world of difference.

Being Socially Isolated

Fatigue throws a huge wrench into social life. It makes it hard to hang out with friends, develop relationships, and just do ‘normal’ teenage stuff. One young person drew themselves in a video game, separated from everyone else in a “bubble” because they were too tired to play.

Cancelling plans or being quiet when out with friends can lead peers to think they have an attitude problem or are unreliable. As one young person put it, “I’m there, but I’m not really there: I’m kind of like a blank canvas.” The effort required to engage is just too much sometimes, leading to withdrawal and a preference for solitary activities. This means they feel like they’re “losing their best years,” unable to fully experience life. Another powerful image was feeling like a “dead tree” – no life, no sparkle, just dull and boring. Parents shared the distress of seeing their children struggle to be socially active at an age when they should be thriving with friends. This isolation brings a whole host of difficult emotions: guilt, fear, worry, anger, sadness, frustration, despair.

Managing Fatigue

Since formal support is often missing, young people and their parents have become experts in managing fatigue themselves. They use strategies based on energy management – trying to preserve energy and find ways to ‘recharge’. This includes things like:

- Rest and sleep

- Activity pacing (breaking things up)

- Staying hydrated

- Eating well

- Multivitamins

- Physical exercise (carefully!)

- Spending time alone (solitude)

It’s their way of trying to assert control over fatigue and their lives. It means constantly making decisions about how to spend their limited energy, prioritising activities, and planning ahead. It requires serious self-regulation and understanding their own bodies and limits. One young person learned that pushing too hard without understanding their limits actually made them *more* tired all the time.

Balancing the need to rest with the need to be ‘productive’ is a constant challenge. They have to make calculations their peers don’t. And the advice to ‘rest and pace yourself’? It often feels totally unrealistic in the face of school, work, and social expectations. As one young person lamented, “Life doesn’t wait for you to rest. Resting and pacing means you’re always playing catch up or missing out or going through life at a mediocre level.” The demands of the world don’t always accommodate the reality of living with chronic fatigue.

The Future While Negotiating Fatigue

Perhaps one of the most heartbreaking findings is the fear and uncertainty fatigue creates about the future. Young people and parents worry intensely about whether they’ll have the energy and capacity to take on adult roles – having a family, holding down a job, being truly independent. The lack of attention to fatigue in clinical care only makes these fears worse.

Fatigue isn’t just impacting their present; it’s limiting their ability to build the skills and experiences needed for adulthood. It can even force them to change their career dreams. One young person gave up her aspiration to be a psychologist because university felt too demanding with her fatigue, opting for an apprenticeship instead – a pragmatic choice based on energy levels, not necessarily passion. Healthcare professionals share these concerns, worrying about the economic potential and independence of young people struggling with fatigue, and the long-term burden on health services.

This study really hammered home that fatigue in SCD isn’t just a side effect; it’s a primary, debilitating symptom that shapes daily life and casts a long shadow over the future. It’s often misunderstood, invisible in healthcare, and leads to painful isolation and stigma.

What’s clear is that we need to do better. Addressing fatigue needs to be a core part of SCD care – in health assessments, in education for patients, parents, and healthcare pros, in school plans, and in public awareness. We need more research to understand it better, develop ways to measure it, and create effective management programs.

Ultimately, these insights aren’t just for SCD. They highlight a broader truth: for any young person living with a long-term condition, fatigue is a huge deal. It’s not secondary; it’s central to their ability to participate in life, learn, grow, and build a future. We need to see it, understand it, and support them through it. Because no young person should feel like they’re just going through life on empty.

Source: Springer