Taking on Esophageal Cancer: Promising Results with a Modern Approach

Hey there! Let’s chat about something pretty important: fighting locally advanced squamous cell oesophageal cancer. It’s a tough one, but folks in the medical world are constantly looking for better ways to tackle it. And honestly, some of the recent findings are giving us real hope.

For a while now, the go-to strategy for these advanced cases has been something called neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy, or NACTRT for short. Think of it as a powerful one-two punch of chemo and radiation *before* surgery. The idea is to shrink the tumor, make surgery easier, and hopefully zap any sneaky cancer cells trying to spread.

Now, most of the big studies that proved NACTRT works came from the Western world. And over there, the most common type of oesophageal cancer is adenocarcinoma. But here’s the thing: in many parts of the world, especially in Asia, the squamous cell type is actually more common. So, we really need to understand how these treatments work specifically for *that* type.

The Esophageal Cancer Puzzle

It turns out that squamous cell oesophageal cancer (ESCC) isn’t just geographically different from adenocarcinoma (EAC); they’ve got different quirks, different ways they grow, and even different genetic blueprints. Knowing these differences is super important because it helps us figure out why they might respond differently to treatment and how they might behave down the line. It’s like trying to solve two different puzzles – they both need a unique approach!

Enter NACTRT and the CROSS Protocol

So, NACTRT followed by surgery became the standard, largely thanks to landmark trials like the “CROSS trial.” This trial showed a clear survival benefit compared to just surgery alone. The CROSS protocol itself is pretty specific: weekly chemotherapy (a platinum-taxane combo) alongside radiation (41.4 Gy in 23 fractions).

But, as I mentioned, the CROSS trial mainly included adenocarcinoma patients. Other studies, like the NEOCRTEC5010 trial from Asia, *did* focus on ESCC and also showed a survival benefit with NACTRT, though they used a slightly different chemo regimen and radiation dose.

These studies consistently show that NACTRT helps doctors achieve “R0 resection,” which basically means they can remove the entire visible tumor with clean margins during surgery – a really good sign! Interestingly, ESCC seems to have a higher “pathological complete response” (pCR) rate after NACTRT compared to EAC. This means that when they look at the removed tissue under a microscope, there’s often *no* sign of cancer left. Pretty cool, right? It suggests squamous cells might be more sensitive to this pre-surgery treatment.

The VMAT Advantage?

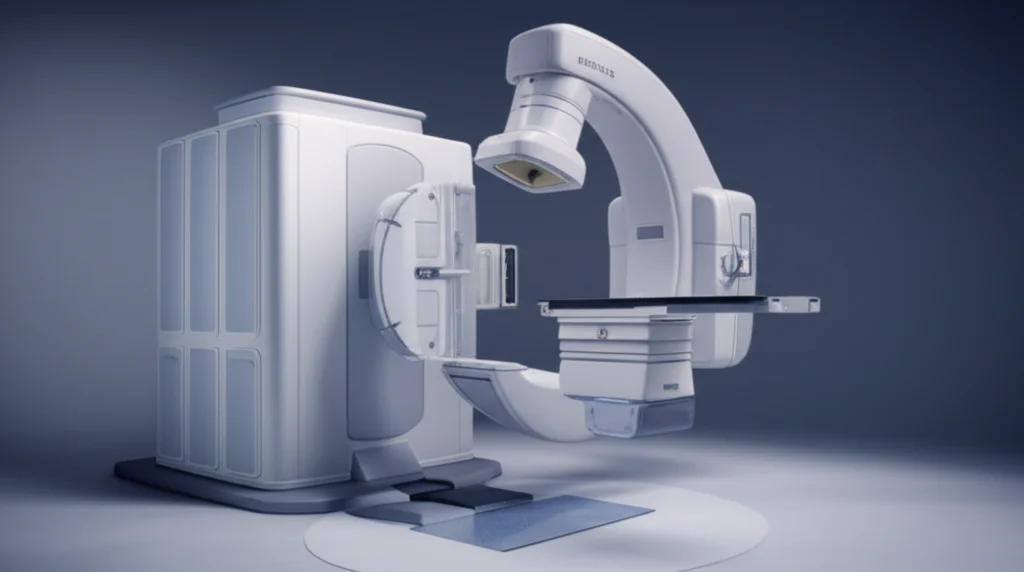

Now, let’s talk about the “how” of the radiation part. Traditionally, many NACTRT trials used a technique called 3D-CRT. It’s effective, but newer technology like Volumetric Modulated Arc Therapy (VMAT) is becoming more common. VMAT is like a super-precise, high-tech way to deliver radiation. It allows doctors to shape the radiation beam much more closely to the tumor, potentially giving it a higher dose while sparing nearby healthy organs like the lungs and heart. The hope is that this precision means fewer side effects, both short-term and long-term.

This study we’re looking at specifically wanted to see the outcomes of using the standard CROSS protocol *but* delivering the radiation using this advanced VMAT technique in patients with locally advanced ESCC.

Diving into the Study

This wasn’t a brand-new trial where they randomly assigned patients to different groups. Instead, it was a look back at data from a single hospital between 2021 and 2022. They gathered information on 102 patients with locally advanced, operable ESCC who all received NACTRT following the CROSS protocol, and *all* of them got their radiation via VMAT.

Before starting treatment, patients went through all the usual checks – endoscopies, PET-CT scans to see if the cancer had spread, and even bronchoscopies if needed. The radiation dose was exactly the CROSS dose (41.4 Gy in 23 fractions), delivered over about 4.5 weeks using VMAT. They also received the standard weekly platinum-taxane chemotherapy.

After finishing NACTRT, patients were checked again with PET-CT scans and endoscopy to see how the treatment worked. If the cancer hadn’t progressed, they went on to surgery, typically about 8 weeks after the radiation finished. Then, they were followed up regularly to see how they were doing.

What We Found

So, what did the data on these 102 patients tell us?

First off, most patients (100 out of 102) completed the planned NACTRT, which is great. Like any strong treatment, there were side effects. The most common ones were mucositis (soreness in the mouth/throat, sometimes needing a feeding tube) in about 16.7% and low white blood cell counts (neutropenia) in about 8.8%. Other side effects like nausea, low sodium, or low platelets were also seen but less frequently.

After NACTRT, most patients were good candidates for surgery. The mean time between finishing radiation and surgery was about 8.2 weeks. Surgery was successful in removing the entire visible tumor (R0 resection) in a fantastic 98% of cases!

And remember that pathological complete response (pCR) I mentioned? In this group, it was observed in 59.4% of patients. That’s higher than what was seen in the original CROSS trial (49% in their ESCC subgroup) and the NEOCRTEC5010 trial (43%). This higher pCR rate is definitely something to note!

Of course, surgery for oesophageal cancer is a major undertaking, and complications can happen. About 32% of patients had major surgical complications (Clavien-Dindo grade ≥ 3). Anastomotic leaks (where the reconnected parts don’t heal properly) occurred in about 17.7%.

Here’s where the VMAT *might* be making a difference: the rates of pulmonary (lung) complications were 17.7%, and cardiac (heart) complications were 5.2%. The study authors suggest these rates might be lower than what’s typically seen with older radiation techniques used in other trials, potentially because VMAT allowed them to spare the lungs and heart more effectively.

Sadly, there were two deaths (2%) shortly after surgery, one from a heart attack and one from infection leading to organ failure.

Looking at the longer term (median follow-up was 29 months), the survival rates were encouraging:

- 3-year Overall Survival (OS): 72%

- 3-year Disease-Free Survival (DFS): 59.1%

- 3-year Local Control (LC): 72%

These numbers compare favorably to other studies on ESCC.

Where did the cancer tend to come back? Locoregional failure (meaning near the original site or in nearby lymph nodes) was the most common pattern, often happening *outside* the area that was directly radiated. The supraclavicular lymph nodes (up near the collarbone) were a frequent spot for this. Distant failures (spread to other organs) also occurred but were less common.

The study also looked at factors that might influence outcomes. They found that having poorly differentiated cancer cells (meaning they look less like normal cells) and “skip lesions” (cancer spots separate from the main tumor) were associated with poorer local control and overall survival.

Putting It All Together

So, what’s the big picture here? This study adds valuable real-world data, especially for ESCC, which is super relevant in places like India where this study was conducted. It reinforces that NACTRT using the CROSS protocol is effective for locally advanced ESCC, leading to good survival rates and high rates of complete tumor removal during surgery.

The higher pathological complete response rate (nearly 60%!) seen in this cohort is particularly exciting and might be linked to ESCC’s potential radiosensitivity, or maybe even the specific combination of the CROSS chemo and the VMAT radiation.

The observation of potentially lower pulmonary and cardiac complications with VMAT is also a big deal. Reducing these complications can make a huge difference in a patient’s recovery and quality of life after major surgery. If VMAT can truly achieve this while maintaining or improving cancer control, that’s a significant step forward.

The study also highlights that the CROSS protocol, even with its weekly chemo, seemed pretty tolerable and feasible, even in settings where access to intensive supportive care might be more limited.

However, it’s important to remember this was a retrospective study from a single center. While the results are very encouraging, especially regarding the pCR rates and potentially reduced cardiopulmonary issues, we can’t definitively say VMAT is *superior* to older techniques based on this study alone. We need more prospective, randomized trials where patients are randomly assigned to different radiation techniques to truly confirm these findings and understand the long-term impact on side effects and quality of life.

The fact that many failures occurred outside the treated area also suggests that researchers need to keep exploring ways to improve local control, perhaps by adjusting the radiation fields or adding other treatments.

Conclusion

Wrapping it up, this study gives us solid evidence that NACTRT using the CROSS protocol is a powerful tool for locally advanced squamous cell oesophageal cancer, leading to impressive pathological complete response rates and good survival outcomes. It seems quite feasible and manageable, even in challenging healthcare environments. The use of VMAT in this study is associated with lower rates of lung and heart complications after surgery, which is fantastic news, although we’re still waiting for larger studies to definitively prove VMAT’s superiority. For now, it’s a really promising piece of the puzzle in improving care for patients facing this disease.

Source: Springer