Elastic Metals: The Next Big Thing in Eco-Friendly Heat Pumping

Hey there! Let me tell you about something pretty cool that’s happening in the world of materials science. We’re talking about a game-changer for how we heat and cool things, and it involves some rather special metals.

You know how we’re all trying to go greener? A huge chunk of the energy we use globally goes into heating and cooling our homes and industries. Right now, a lot of that relies on burning fossil fuels, which, let’s face it, isn’t great for the planet. There’s also this technology called vapor compression heat pumping, which is more efficient, but it often uses refrigerants that have a nasty habit of contributing to global warming. So, yeah, we urgently need better, cleaner ways to manage heat.

The Quest for Green Heat Pumps

For a while now, folks have been looking at solid-state alternatives. Think materials that can heat up or cool down when you apply a force or a field, without needing those questionable gasses. Shape memory alloys (SMAs) have been a big focus. These materials can undergo phase transitions – basically, changing their internal structure – when you stress them, and this transition can absorb or release heat. It’s pretty neat, and some devices have been built using them.

But here’s the rub: these phase transitions often come with a bit of a hiccup called *hysteresis*. Imagine trying to push a door open, and it sticks a little before it moves, and then sticks again when you try to close it. That sticking is like hysteresis – it means you lose some energy in the process. For heat pumps, this hysteresis limits how efficient they can be. SMAs, while promising, often only hit about 50-70% of the theoretical maximum efficiency (called the Carnot limit), while those traditional vapor compression systems can get closer to 90%. We need that higher efficiency!

A Different Path: The Thermoelastic Effect

So, what if we could skip the messy phase transition altogether? That’s where this new work comes in. They’re proposing using something called the *thermoelastic effect* (TeE) in a specific kind of material: the *martensitic phase* of *ferroelastic alloys*.

Now, the TeE isn’t new. Guys like Kelvin and Joule talked about it ages ago. It’s a fundamental property of linear-elastic solids. Basically, when you squeeze a material really fast, it gets a little warmer. When you stretch it really fast, it gets a little cooler (assuming it expands when heated, which most things do).

The catch? For most everyday metals, this effect is tiny. We’re talking a temperature change of maybe 0.2 Kelvin. Not exactly going to heat your house or cool your fridge. Because it seemed so weak, not many people have seriously looked at using it for practical heat pumping for centuries.

The Secret Ingredient: Giant Thermal Expansion

But these clever scientists, guided by theory, had a hunch. What if you could find a material where this thermoelastic effect *wasn’t* tiny? According to the physics, the amount of temperature change you get from elastic deformation depends a lot on the material’s *linear thermal expansion* (how much it expands or contracts with temperature) and how much stress you apply. If you have a material with a *huge* thermal expansion coefficient, you should get a much bigger temperature change for the same amount of stress.

And guess what? The *martensitic phase* in *ferroelastic alloys* turns out to be just the ticket! These materials have a unique property: their intrinsic thermal expansion can be massive, especially along certain directions in their crystal structure, and it gets even bigger as you get close to the temperature where they’d want to transform into a different phase (their instability temperature, or As point). We’re talking thermal expansion 10 to 50 times larger than common metals!

Enter Ti78Nb22: A Star Performer

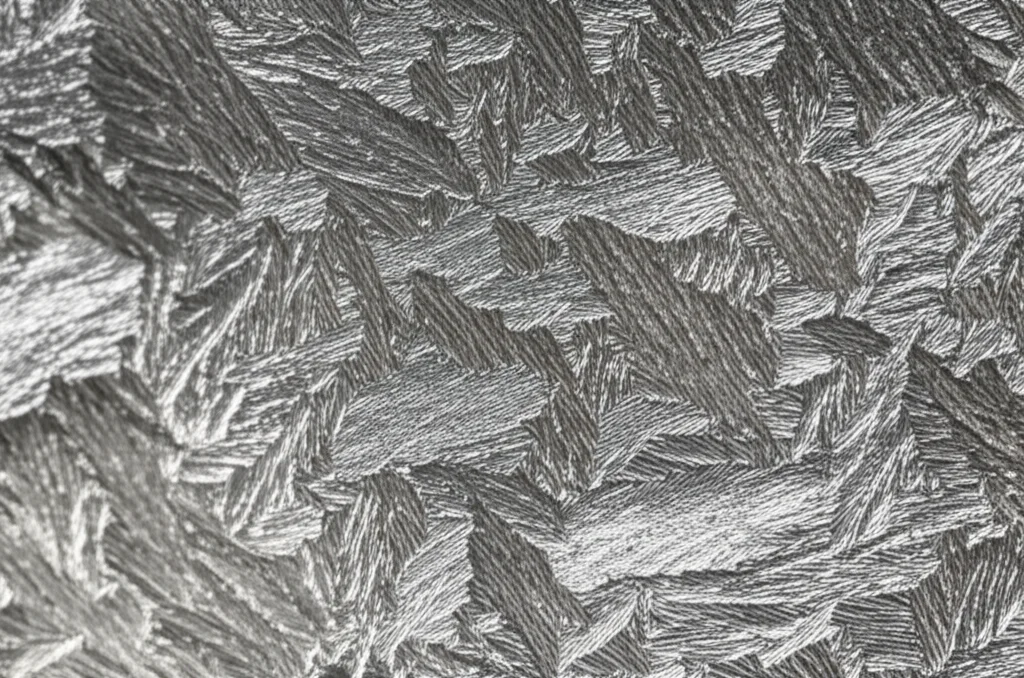

So, the researchers decided to test this idea. They focused on a specific *ferroelastic alloy* called *Ti78Nb22* (that’s Titanium with 22% Niobium). To make the most of that giant intrinsic thermal expansion, they processed the material carefully using cold rolling and compression to create a specific texture – essentially aligning the crystals so the direction with the big thermal expansion was lined up correctly. They ended up with what they call “[100]-textured *Ti78Nb22*”.

They checked that this material stayed in its *martensitic phase* even when heated up quite a bit, meaning they avoided that problematic phase transition. And then they squeezed it.

Here’s where it gets exciting: under a moderate stress (700 MPa), they measured a *large adiabatic temperature change* (that’s the ∆Tad we talked about) of 4 to 5.2 Kelvin! This happened at temperatures between 413K and 473K (that’s roughly 140°C to 200°C), which is a really useful range for industrial heat applications. Remember that 0.2K for ordinary metals? Yeah, 4-5K is *way* better. It also blows past the TeE seen in polymers, glasses, and ceramics.

Efficiency and Durability: The Winning Combo

But the temperature change isn’t the only win. Because this effect relies on *elastic deformation* – essentially just stretching and squeezing the material like a spring, which is inherently very reversible – there’s very little hysteresis. This translates directly into *high energy efficiency*.

They calculated the potential efficiency of this *Ti78Nb22* in a heat pumping cycle. The result? An incredible 88% of the Carnot theoretical limit! At higher temperatures, it could even reach 94%! This rivals the efficiency of the best vapor compression systems and is significantly better than the 50-70% typically seen with phase-transition SMAs.

And what about durability? Could the material handle being squeezed and released over and over? They tested it. At 473K, it showed no significant degradation in the TeE over a thousand cycles. At room temperature, it held up for *10 million* cycles! While there was a tiny bit of permanent deformation initially (a little like breaking in a new pair of shoes), it quickly stabilized, showing almost zero hysteresis loop area after that. This *cyclic stability* is a huge deal for practical applications.

This means this *Ti78Nb22* material, with its combination of large temperature change, high efficiency, and excellent durability at useful temperatures, looks like a fantastic candidate for energy-efficient heat pumps, especially for industrial processes that need heat in that 373-503K range. Imagine the energy savings and reduced emissions!

Looking Ahead: Even Bigger Effects?

The researchers didn’t stop there. They realized that in their *Ti78Nb22* polycrystals, they were only tapping into about a third of the material’s *maximum intrinsic thermal expansion*. What if you could get single crystals, or even better textured polycrystals, that fully utilized that giant expansion along the most favorable direction?

Using their theory, they predicted the TeE for single crystals of *Ti78Nb22* and several other *ferroelastic alloys* known to have even larger intrinsic thermal expansion coefficients (up to 5.4 x 10^-4 /K). The predictions are jaw-dropping: *adiabatic temperature changes* of 9 to 22 Kelvin under moderate stress! These large effects would occur near the alloys’ respective As points, which range from 155K to 480K. This suggests the potential for highly efficient heat pumping and cooling across a wide range of temperatures, from below room temperature to well above.

The key takeaway here is that by focusing on the *thermoelastic effect* in the *martensitic phase* of *ferroelastic alloys*, specifically those with giant intrinsic thermal expansion, we open up a whole new avenue for solid-state heat pumping. It’s a pathway that avoids the efficiency limitations of phase transition hysteresis and offers the potential for high performance, high efficiency, and excellent durability.

Think about it: using the simple, reversible act of stretching and squeezing special metals to move heat around, efficiently and cleanly. It’s a brilliant idea, rooted in old physics but unlocked by modern materials science. This research isn’t just a lab curiosity; it’s a significant step towards the next generation of heating and cooling technology. Pretty cool, right?

Source: Springer