Alzheimer’s Earliest Spark? Hyperactive Mossy Cells Sound the Alarm

Hey there! Let’s talk about something super important, something that touches so many lives: Alzheimer’s disease. We’re all looking for ways to understand it better, especially how it starts, because finding those early signs is key to fighting it. Think of it like catching a tiny spark before it becomes a wildfire.

For a long time, we’ve known that Alzheimer’s messes with memory, and we see those infamous amyloid plaques and tau tangles in the brain. But what happens right at the *very beginning*? What are those first whispers of trouble?

One idea gaining traction is that the brain becomes *too excited* early on in Alzheimer’s. Not excited like “Yay, cake!” but electrically overactive. You see signs of this hyperexcitability in people with early memory issues, sometimes even showing up as seizure-like activity. And guess what? We see similar things in mouse models designed to mimic Alzheimer’s. It’s like the brain’s electrical system starts buzzing too loudly.

Why does this matter? Well, studies in these mouse models have shown that if you can calm down this overexcitement, you can actually help their memory and even reduce some of the Alzheimer’s-like gunk building up. Pretty cool, right? But the big question has been: *how* does this hyperexcitability start, and *where*?

Setting the Stage – The Brain’s Gatekeeper and Early AD

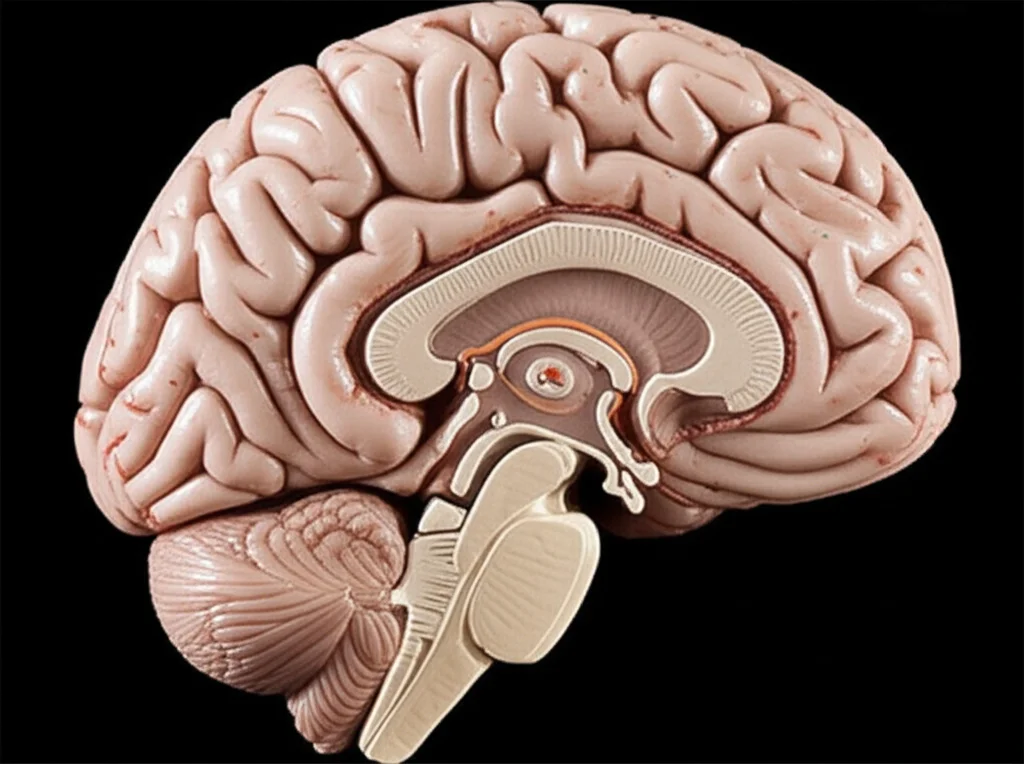

Our brain has different neighborhoods, and one crucial spot for memory and learning is the hippocampus. It’s often one of the first places hit by Alzheimer’s. Within the hippocampus is a special area called the *dentate gyrus* (DG). Think of the DG as a strict gatekeeper. Normally, it’s pretty quiet, keeping a lid on electrical activity, almost like a filter. This low excitability is thanks to its main residents, the *granule cells* (GCs), and a bunch of inhibitory neurons that act like bouncers. This gatekeeper role is super important, not just for memory but also for preventing runaway electrical storms, like those seen in epilepsy.

But when the DG’s gatekeeper function gets messed up, things go haywire. Its normal jobs, like helping you tell similar memories apart or noticing new things, get harder. And in Alzheimer’s models, this DG seems to become *more* excitable.

We’ve been studying one particular mouse model called Tg2576. These mice have a genetic tweak that makes them produce a lot of a specific protein fragment linked to Alzheimer’s, called amyloid-beta (Aβ). These mice develop Alzheimer’s-like symptoms relatively slowly, which is great for scientists like us because it lets us look at those really early stages. We’ve seen signs of electrical overactivity in these mice as young as one month old – way before they show memory problems or big amyloid plaques.

Our previous work looked at the main cells in the DG, the GCs, in slightly older Tg2576 mice (around 3 months). We saw they were getting more excitatory messages, and some of their own electrical properties were changing, maybe trying to compensate for the extra buzz. But we wondered, what’s happening even *earlier*, at just one month? And what’s *causing* that increased buzz in the GCs?

Meeting the Mossy Cells – The DG’s Conductors

This is where another important cell type in the DG comes in: the *mossy cells* (MCs). These guys live in the neighborhood next door to the GCs and are one of the main ways GCs get excited. MCs are like conductors in this brain orchestra, sending signals directly to the GCs. But it’s a bit complicated because MCs also talk to those inhibitory bouncer neurons, which then tell the GCs to quiet down. So, the net effect of MC activity on GCs has been a bit of a puzzle – could they excite GCs, or actually help inhibit them? It seems it might depend on the situation.

Despite their important role in the DG, MCs haven’t really been in the spotlight when it comes to Alzheimer’s research. So, we had a hunch: could these MCs be involved in that *very early* hyperexcitability we see in the Tg2576 mice?

The Study’s Deep Dive – What We Found

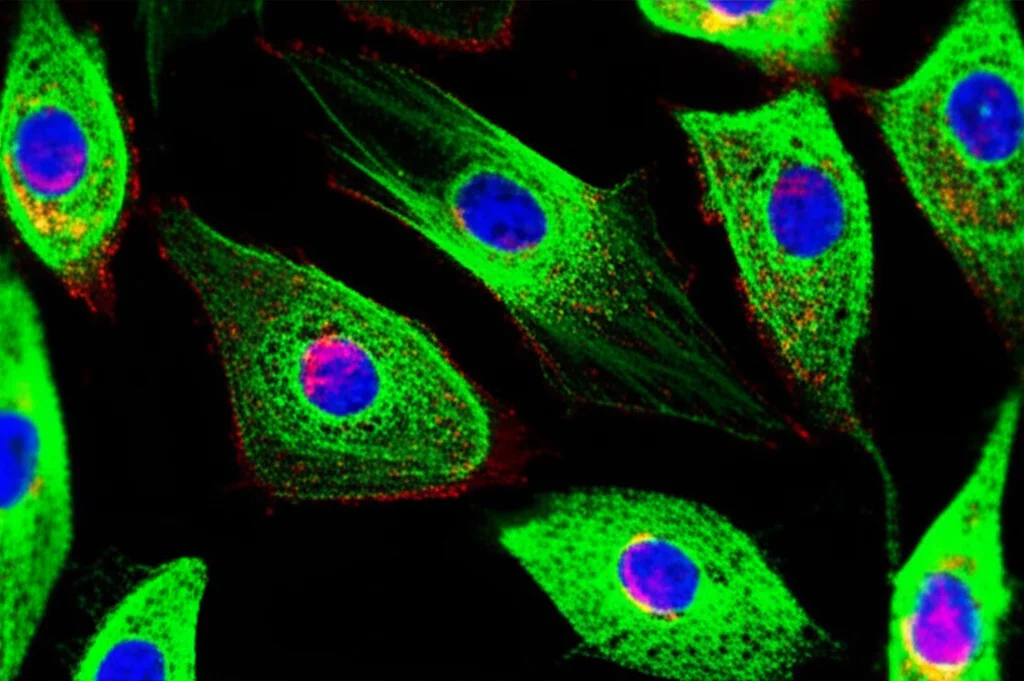

To figure this out, we got up close and personal with the brains of one-month-old Tg2576 mice and compared them to regular, healthy mice. We used fancy techniques to listen in on the electrical conversations happening in brain slices, specifically in the MCs and GCs. We looked at the tiny electrical signals coming into these cells (synaptic activity) and also their own inherent ability to fire (intrinsic properties). We also checked for markers of activity and looked at the structure of MC connections.

Here’s what we discovered about the *Mossy Cells* in the young Tg2576 mice:

- They were receiving *more excitatory signals* than MCs in healthy mice.

- At the same time, they were receiving *fewer inhibitory signals*.

- This created a clear *imbalance*, tipping the scales towards excitation – basically, making them more likely to get fired up.

- Beyond just the incoming signals, the MCs themselves seemed *intrinsically more excitable*. It took less effort to make them fire an electrical pulse, and they fired faster once they started.

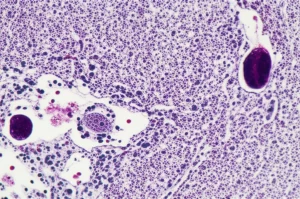

- To back this up, when we looked at the brains of these mice, we saw that MCs in the Tg2576 mice showed *higher levels of c-Fos*, a protein marker that tells us which neurons have been electrically active recently. This confirmed our “listening in” findings were happening in the living mouse too.

- Interestingly, we found *increased amounts of amyloid-beta protein *inside* the MCs* themselves at this early age. This suggests that maybe this early build-up of Aβ inside the cells is somehow making them overactive.

Now, what about the *Granule Cells*? Remember, these are the main cells that MCs talk to. In the young Tg2576 mice:

- They were getting *more excitatory signals* AND *more inhibitory signals*. This might sound contradictory, but it fits with MCs exciting both GCs directly and the inhibitory bouncer neurons indirectly.

- However, unlike the MCs, the GCs’ *own intrinsic firing properties* didn’t seem changed *yet* at this early age. This is different from what we saw in older mice, suggesting synaptic changes happen first.

- Crucially, when we used a substance that blocks the connection from MCs to GCs, it *reduced the extra excitation* we saw in the Tg2576 GCs, bringing it closer to normal levels. This strongly suggests MCs are indeed driving some of this early GC buzz.

We also took a look at the physical connections. Using a marker for MCs, we saw that their axons (the parts that send signals) seemed to be *sprouting* or extending more into the area where GC dendrites (the parts that receive signals) are located in the Tg2576 mice. This physical change could be another reason why GCs are getting more input from MCs.

What Does It All Mean? – Before Memory Fades

So, putting it all together, our study paints a picture where the *mossy cells* are getting overexcited *very early* in this Alzheimer’s mouse model. This overexcitement seems to be caused by a mix of getting more excitatory messages, fewer inhibitory messages, and changes in their own electrical properties, possibly linked to amyloid-beta building up inside them.

This early MC hyperexcitability then appears to be influencing the *granule cells*, leading to increased incoming signals (both excitatory and inhibitory) to GCs, even before the GCs’ own firing properties change. The fact that blocking MC input calms down the GCs supports this idea. The physical sprouting of MC axons towards GCs also suggests a stronger connection is forming.

Here’s the really important part: *all of these cellular and synaptic changes in the DG were happening at one month of age, *before* the mice showed any problems with a memory task* (called Novel Object Recognition, which tests if they remember a familiar object). This is huge! It means these changes in cells like MCs aren’t just a consequence of advanced disease; they are happening right at the *very beginning*, potentially setting the stage for later problems.

Think of it like this: the MCs are like the first few instruments in the orchestra starting to play too loudly and a bit off-key, long before the whole symphony sounds wrong and the audience (the person’s memory) notices the problem.

Why does this matter for us?

- It suggests that the hyperexcitability in Alzheimer’s might start with specific cells like the mossy cells.

- These early changes in MCs could potentially serve as *biomarkers* – early warning signs we could look for.

- Most excitingly, if we can identify these early culprits and understand *why* they become overexcited (like the potential role of intracellular Aβ), we might be able to develop treatments that target these specific cells or processes *before* significant memory loss occurs.

Conclusion

In a nutshell, our work in this mouse model points to dentate gyrus mossy cells as potential early players in the Alzheimer’s story. Their increased excitability and altered connections seem to be among the very first changes in the DG, potentially contributing to the brain’s electrical overactivity that happens long before memory starts to slip. It opens up exciting new avenues for research, suggesting we might find ways to intervene much earlier than we thought possible, potentially changing the course of the disease. It’s a small piece of the puzzle, but an important one in the quest to understand and ultimately treat Alzheimer’s.

Source: Springer