Duckweed: Our Secret Weapon Against Climate Chaos?

Hey there! So, let’s talk about something pretty wild. We hear a lot about climate change, rising temperatures, and how it’s messing with our food supply, right? It’s a big deal, and honestly, it can feel a bit overwhelming. The experts are saying that by 2050, global crop yields could drop by a whopping 25% because of all this extreme weather – droughts, floods, heatwaves, you name it. And let’s not even get started on the really scary stuff, like the potential for massive conflicts or even, heaven forbid, a nuclear war, which could plunge us into a sudden, dark, and freezing world where growing food as we know it becomes nearly impossible. We’re talking potential 90% drops in global calorie production in those worst-case scenarios. Food security is already a huge issue for over 30% of the planet, and these future shocks are only going to make things tougher.

The Looming Food Crisis

It feels like we’re living through a time where access to food is getting harder for more and more people. Reports from big organizations like the FAO and WFP show millions are already facing severe food insecurity. Climate change isn’t just a future threat; it’s actively contributing to this instability *now*. Extreme weather events are already slashing agricultural productivity. Think about it – between 2008 and 2018, natural disasters caused 63% of farming losses in lower and middle-income countries. And the forecast isn’t great: we’re expecting more frequent, intense, and widespread extreme weather. Someone born in 2020 might face two to seven times more extreme weather events than someone born in 1960. That’s a stark picture, isn’t it?

Beyond the gradual changes, there are also those abrupt, catastrophic possibilities – super volcanic eruptions or nuclear war. These events could cause sudden, drastic cooling due to stuff like soot or aerosols blocking out the sun. We’ve seen hints of this before, like the famines after volcanic eruptions in the 1700s and 1800s. Simulation models for a full-scale nuclear war paint a terrifying picture of billions dying from hunger as temperatures plummet, especially in the Northern Hemisphere. Even a smaller conflict could put billions at risk. While global warming heats things up and nuclear winter cools them down, both scenarios hammer traditional agriculture. It’s clear we need food sources that are incredibly resilient, able to handle wild swings in temperature and light.

Historically, we’ve tried to breed crops that can tough it out, using genetic engineering to create varieties resistant to droughts or floods. And that’s great, don’t get me wrong! Transgenic rice, for example, is more resilient. But even these super-crops might fail if conditions get *really* extreme, outside the predicted ranges. An India-Pakistan nuclear war, for instance, could devastate rice farming in China. So, while we keep working on making traditional crops tougher, we *desperately* need alternative crops that can grow when everything else fails. Given that climate disasters are becoming way more frequent (five times more in the last 50 years!) and the threat of nuclear war is, disturbingly, on the rise, finding and integrating new, resilient crops into our system is becoming super urgent. It’s not just about disaster preparedness; it’s about building a more sustainable system *now*, less dependent on conventional crops.

Enter the Mighty Duckweed

Now, enter our unlikely hero: Lemnaceae, or as you probably know it, duckweed. You’ve probably seen it – that bright green carpet covering ponds. Most people think of it as a weed, but this little aquatic plant is incredibly robust and grows like crazy. Scientists have been looking into it for years, not just for cleaning water, but as a potential food source. And get this: it’s packed with protein, up to 45%! That’s huge. It’s being explored for human food, animal feed, even bioenergy and fertilizer. Lately, it’s gaining buzz as an eco-friendly, whole-protein superfood, a potential alternative to meat protein.

But its real superpower, in the context of our shaky future, is its resilience. Duckweed can handle a massive range of temperatures (5–33°C) and pH levels. Crucially, it can grow even in very low light, making it a promising candidate for those cold, dark post-nuclear-war scenarios. Other resilient crops like quinoa, millet, and sorghum are great too, especially for drought and poor soil. But duckweed has some distinct advantages:

- Higher productivity: You can harvest it multiple times a year.

- Less water use: For the amount of biomass produced, it’s incredibly water-efficient.

- Higher protein content: It can yield five to ten times more protein than land crops like soybean per area.

- Non-arable land: It grows on water, freeing up valuable land for other uses. It can even thrive in wastewater, doing double duty by cleaning the water and producing food!

While fresh duckweed is low calorie, dried and powdered, it’s a calorie and protein powerhouse, potentially offering more calories per 100g than chicken or beef. Plus, you can grow it indoors in vertical farms, meaning you could potentially have a protein source even if outdoor conditions are impossible or supply chains collapse.

Putting Duckweed to the Test: The Study

So, these clever folks decided to put duckweed’s resilience to the ultimate test. They used plant growth models, coupled with climate data, to predict how duckweed would fare under different future scenarios. They looked at two global warming pathways – an optimistic low-emission one and a fossil-fuel-heavy high-emission one. And they examined three post-nuclear-war cases with varying amounts of atmospheric soot injection, from a smaller regional conflict to a large-scale war. They simulated duckweed growth across 20 locations worldwide to see how yields would change. This is apparently the first time duckweed growth models have been used with these extreme climate scenarios, providing scientific backing for just how tough this plant is and where it might grow best when things get weird.

The model they used is pretty sophisticated, considering things like temperature, light intensity, mat density (how thick the duckweed is), photoperiod (day length), and nutrients. They even adjusted it to account for duckweed dying below 5°C. They simulated optimal harvesting practices over a full year to get annual yield predictions. The climate data came from reputable sources, covering historical periods and projections out to 2050 for global warming, and simulating the drastic cooling and darkening effects of nuclear winter scenarios for 15 years post-event. They looked at how Duckweed’s Growing Degree Days (GDD) changed too – basically, a measure of heat accumulation needed for growth.

Duckweed vs. Global Warming: A Mixed Bag

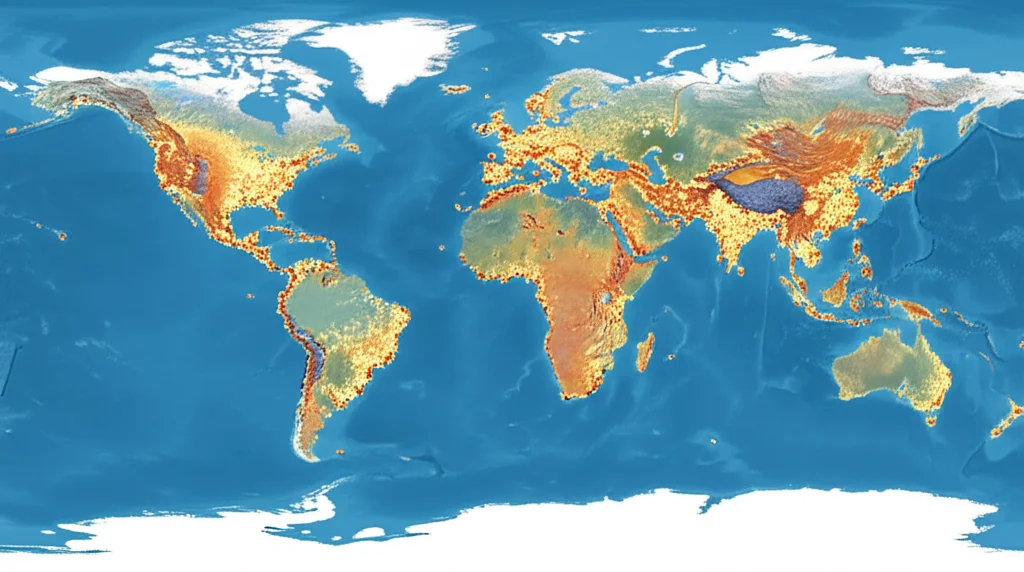

What did they find? Well, historically, duckweed yields are highest near the equator, decreasing as you go towards the poles. This makes sense – it likes warmth, but not *too* much heat, and definitely not freezing conditions. The study’s baseline data matched real-world yields pretty well (10-30 metric ton/ha/year).

Under the global warming scenarios, things got interesting. Equatorial regions saw minimal impact on yields – less than a 6% change, even in the high-emission scenario. In fact, some tropical areas might see a slight *decrease* if it gets too hot, which aligns with other studies showing duckweed growth slows above 35°C. But here’s the cool part: in the colder northern regions, global warming actually *increased* duckweed yields significantly, up to 90% in some spots! Warmer temperatures meant better conditions for growth, potentially allowing duckweed to thrive further north, much like how other plant species are migrating poleward. Southern regions also saw slight increases. The year-to-year variability was also pretty low in equatorial and southern regions, suggesting stable yields. Northern regions showed more variability, but overall, the trend was positive in most northern locations, except for one spot in Canada where temperatures were projected to drop below historical averages. This resilience to changing temperatures, especially the benefit in warming northern areas, really highlights duckweed’s potential as the climate shifts.

The growing season length also changed. In those warming northern areas, the growing season started earlier. This aligns with other studies showing earlier plant growth and algal blooms in warming climates. While the growing season changes weren’t massive overall, the fact that warmer temperatures in historically cold places benefit duckweed’s growth cycle is a big plus. They also looked at GDD. As expected, northern regions saw increased GDD with warming (except that one Canadian spot), correlating nicely with the increased yields. This confirms that GDD is a good predictor for duckweed yield, and that warmer conditions (up to a point) are beneficial.

Duckweed vs. Nuclear Winter: Survival Mode

Now for the really extreme stuff: nuclear winter. This is where duckweed’s low-light and cold tolerance is truly tested. As expected, increasing soot injection (meaning colder and darker conditions) led to reduced yields everywhere. But the equatorial regions, again, showed the most resilience. Even in the worst-case 150 Tg soot injection scenario (a full-scale US-Russia war), equatorial yields only dropped by about 21% compared to normal. While that’s a significant drop, it still leaves potential yields of 19-20 metric ton/ha/year. That’s huge! When conventional crops in these scenarios are predicted to fail almost entirely in higher latitudes, having *any* significant food production is critical.

Southern regions were also somewhat resilient in the milder nuclear winter scenario but saw bigger losses (up to ~41%) in the most extreme case. The hardest hit were the northern regions, where yields could plummet by over 80%. In some northern locations, the model predicted zero yield in the immediate years after a severe nuclear war because conditions were too cold and dark for the duckweed to even reach the minimum density needed for harvesting. This aligns with predictions that mid-to-high latitudes would face massive calorie reductions, potentially 100% in northern countries, after a large nuclear war.

Looking at the year-to-year changes after a nuclear war, the first 5-6 years are the toughest, especially for higher latitudes, with yields dropping significantly before slowly recovering. Even in the milder nuclear winter scenario, traditional crops like maize, rice, and soybean in high latitudes could see over 75% yield reduction in the first 5 years. Duckweed’s ability to maintain *some* yield, especially in lower latitudes, is a major advantage. While 19-20 metric ton/ha/year might be less than ideal, in a post-catastrophe world where other food sources are gone, it could be a lifeline for meeting protein needs.

The nuclear winter scenarios also drastically impacted GDD and growing seasons, particularly in higher latitudes. The cold and dark delayed or completely prevented growth for years in the north. Equatorial regions saw less impact on growing seasons, but the most extreme scenario could still delay harvests by a month. The significant drop in GDD in the years after a nuclear war, even in equatorial regions, underscores the severity of the conditions. This study is the first to document duckweed GDD, and the strong positive correlation between GDD and yield holds true even in these extreme cold scenarios.

Why Duckweed is Our Unlikely Champion

So, what’s the takeaway from all this modeling? Duckweed is seriously resilient. Global warming might even make it easier to grow in some places that are currently too cold. Nuclear winter is a much harsher test, but duckweed still shows remarkable potential, especially in equatorial regions, where it could provide a vital protein source when other crops fail.

Think about it: livestock, a major protein source now, would be incredibly vulnerable in these scenarios. Duckweed offers a high-protein alternative that grows fast and doesn’t need arable land. The study even did a preliminary calculation: a two-person household could meet 20% of their annual protein needs by vertically farming duckweed in a relatively small indoor space (~20 m² footprint). To get the same protein from outdoor soybean farming, you’d need over four times the area.

Now, duckweed isn’t a magic bullet. It’s low in fat, so a post-catastrophe diet would need other sources for complete nutrition. But as a high-yield, resilient protein base, it’s incredibly promising.

Bringing Duckweed to the Table: Challenges and the Future

Of course, getting duckweed onto plates globally isn’t just about science; it’s about people and logistics. In many Western countries, people see it as a weed, not food. We need to change that perception, highlighting its sustainability and resilience benefits. It’s already popular in parts of Asia, which is a great starting point.

Logistically, pond cultivation is simple and great for small farmers, especially in tropical areas where yields are stable. But scaling up needs better harvesting and processing tech. For wealthier regions where nuclear winter could make outdoor farming impossible, indoor vertical farming is an option, though it’s expensive and energy-intensive. Policy support, investment, and education are key to overcoming these hurdles and integrating duckweed into our food systems.

Acknowledging the Science: Study Limitations

The scientists are super upfront about the study’s limitations. It used only one climate model for global warming and data from only two for nuclear winter, which introduces some uncertainty. They also couldn’t account for changes in atmospheric CO2 or nutrient levels, which *do* affect duckweed growth in the real world. The model was originally for controlled indoor settings, and applying it globally outdoors has challenges, like assuming constant nutrient availability everywhere. Real-world factors like salinity, pH, or competition from other plants could also affect yields. Future research needs to use more models, include more variables, and importantly, do field trials to see how duckweed actually grows in these varied conditions.

The Big Picture: Duckweed’s Role in a Shaky Future

So, what’s the big picture here? This study gives us solid scientific evidence that duckweed is incredibly resilient to both the gradual changes of global warming and the sudden, extreme shock of nuclear winter. It shows that while global warming might open up new growing areas in the north, nuclear winter would make those same areas incredibly challenging, highlighting the need for indoor solutions there. But crucially, in many parts of the world, especially near the equator, duckweed could still produce significant yields even in the face of catastrophe.

This work isn’t just about duckweed; it’s a call to action. We need to invest in resilient, sustainable, and locally available food sources. Duckweed, with its high protein content, rapid growth, and ability to thrive in tough conditions, is a prime candidate. Integrating it into our agricultural strategies, supporting its cultivation, and educating people about its benefits could be a vital step in enhancing global food security in an increasingly uncertain future. It’s a tiny plant, but it could play a massive role.

Source: Springer