Spilling the Beans (or Dreams!): What It’s Really Like to Talk About Your Nightly Adventures in Therapy Training

Ever woken up from a bizarre dream and thought, ‘What on earth was THAT about?’ And then, imagine having to spill all those weird, wonderful, or downright worrying details to your psychoanalyst during your own training. It’s a pretty unique experience, right? Well, I’ve been digging into a fascinating German study that did just that – it explored what it’s really like for psychotherapists in training to talk about their own dreams during their ‘Lehranalyse,’ or training analysis. It’s not just about the dreams themselves, but the whole shebang of telling them, and what that feels like. As one interviewee put it, “Dreams themselves are very creative, where you basically write pictures or films in the middle of the night. You sleep, and you create films, and that’s already incredible.”

Why Dreams, Anyway? A Quick Trip Down Memory Lane

Dreams have been puzzling and captivating us for ages, long before psychoanalysis jumped into the ring. Freud, bless his cotton socks, really put them on the map with his “The Interpretation of Dreams.” He saw them as a vital component of his theory of the unconscious, arguing they weren’t just random brain firings (as medicine at the time thought) but had meaning, pointing to the dreamer’s unconscious motives and wishes. Every dream, Freud reckoned, was a wish fulfillment, often rooted in “repressed wishes…of infantile origin.” But this wasn’t obvious in the dream we remember (the manifest content) because the unconscious meaning (latent content) was disguised by ‘dream work’ – think condensation, displacement, and symbolization. The idea was that analysis, using the dreamer’s associations, could kind of reverse-engineer this process.

Jung, on the other hand, focused heavily on the symbols in dreams, emphasizing archetypal interpretations where dreams were a direct expression of the collective unconscious. He also highlighted interpreting dreams on the ‘subject level,’ meaning dreams show different sides of the dreamer’s personality, especially those not fully expressed in waking life. Over time, many other psychoanalytic thinkers have chimed in, tweaking theories and techniques. Object relations theorists, for instance, gave more weight to the transference aspect of dreams, seeing the analyst as a primary object helping to ‘metabolize’ dreams. Some even shifted away from seeing dreams as super special, like the Kris group, who thought dream reports were just another form of communication. Others, like Morgenthaler, emphasized the process of dream telling and the importance of analysts being moved by their patients’ dreams. Ermann, in the intersubjective camp, called for a “shift from content to relationship analysis,” treating dream reports like any other free association and using them to explore the here-and-now of the therapeutic relationship.

So, What’s the Big Deal About Talking Dreams in Training?

A study by Henkel et al. (2020) looked at how practicing analysts view dream work, finding it plays a huge role and is seen as multifaceted and fascinating. But what about the folks on the couch, especially those training to be therapists themselves? That’s where this newer research comes in. The researchers decided to interview training analysands because, frankly, there’s not a ton of research on their experiences. The big question was: How do candidates in training for psychotherapy experience working with their own dreams in their training analysis?

They conducted five less-structured, problem-centered interviews with individuals in psychoanalytic/psychodynamic training who were undergoing analysis on the couch. These weren’t just any chats; they used a method involving a short questionnaire, an interview guide (though they kept it pretty open-ended to encourage natural storytelling), audio recording, and a postscript for immediate reflections. The sample included psychologists and doctors, male and female, aged between 20-30 and 40-50, all reporting dreams in their analysis occasionally to often. The transcribed interviews were then analyzed using Constructivist Grounded Theory, which is a fancy way of saying they let the themes emerge from the data itself. This led to three core categories: the analytic framework, becoming visible, and mutual construction.

Setting the Stage: The “Analytic Framework”

This first category, the (Training) Analytic Framework, is all about the environment in which dreams are told. Think of it as the foundation, the safe harbor. The interviewees described this framework as crucial for even being able to talk about their dreams and verbalize their own issues. It’s shaped by a therapeutic attitude that offers reliability and safety, soothing potential worries. How the analyst handles the dream is a biggie. Descriptions included the analyst being reserved, conveying openness, and encouraging a feeling of freedom. Knowing how their analyst approaches dreams was reported as trust-building. That predictability, like a ritual or script, offered security. One person said, “…if it was a disturbing dream, then it’s a nice feeling to know I have someone who will talk it through with me. Then the analyst, so to speak, has a containing function for me, to calm it down, to make it understandable.”

Conversely, uncertainty about the analyst’s approach could stir up anxiety. One trainee mentioned fearing potential interpretations before sharing her first dream. But generally, the training analysis was seen as a space to process unsettling dreams, making those disturbing feelings understandable. This idea of the analyst providing a “containing function” echoes object relations theories, where the analyst helps process raw, unconscious material, much like a primary caregiver would for an infant.

The “Becoming Visible” Tightrope Walk

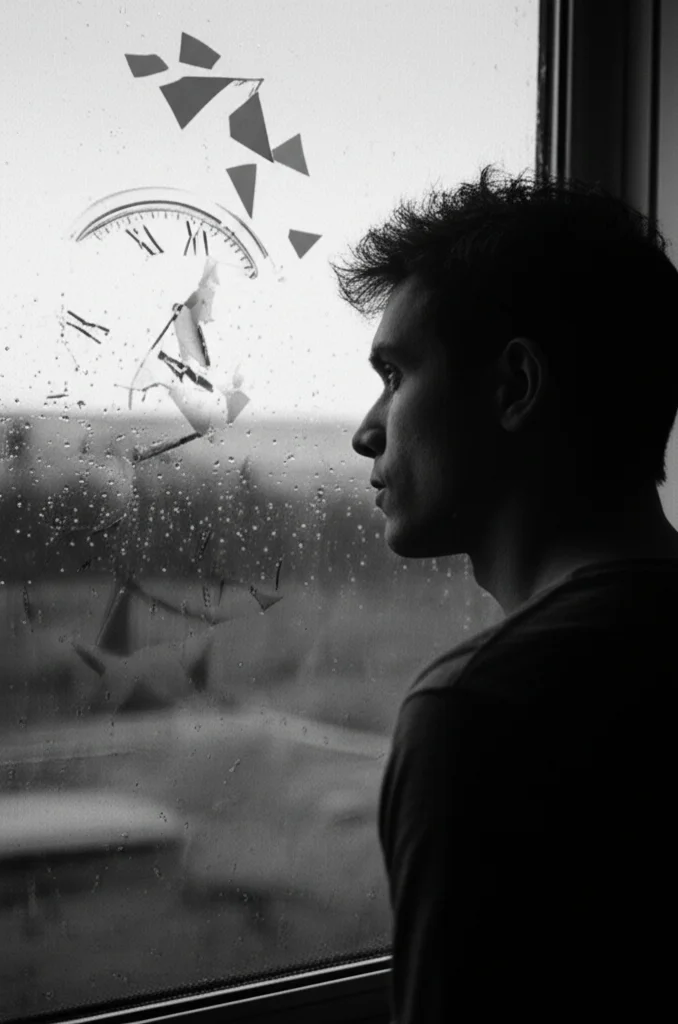

Now, this is where it gets really personal. The category of Becoming Visible captures the experience of trainees feeling like they are revealing themselves through their dream narratives. The term itself was chosen to be neutral, neither good nor bad. It’s about showing oneself, inviting the analyst to look at one’s personal themes. Dreams were described as catalysts, bringing certain issues to the surface, sometimes “unsparingly,” like a “loud bang.”

This self-revelation can feel like being put on display, even a bit exhibitionistic. One trainee found it exciting to hear and explore others’ dreams for her future professional role, but struggled with being in the position of showing herself. This can be threatening because parts of the self one doesn’t want to show might be seen. Feelings of being “naked” and defenseless can pop up, or fears of being at the mercy of the analyst through a dream. One interviewee shared, “…the first dream was impressive for me because the therapeutic relationship was depicted in a way that I couldn’t have put into words at that time. … That the dream could express something better than I could have consciously said in words.”

But here’s the flip side: dreams can also be a massive help. They can be a “vehicle” to broach difficult topics, especially concerning the relationship with the training analyst. It’s like the dream provides the language for what’s hard to articulate. For some issues, it’s easier to talk via a dream. The “blame” can be put on the dream, which can be a relief, especially for taboo thoughts, wishes, or fears. It’s as if what’s expressed in the dream is experienced as somewhat separate, not entirely belonging to the conscious self. The old biblical phrase “It dreamed us” captures this sense of dreams being something that “happens to us,” outside our conscious control, yet undeniably our own construction.

So, there’s this real ambivalence: a wish to be seen and understood by the analyst, tangled up with the fear of it. Shame plays a big role here. It can be about the dream content, how it’s understood, or associations to it. This might lead to talking about the dream with embarrassed amusement, laughing it off, or introducing it in a roundabout, explanatory way. If the shame is too intense, the dream might not be told at all. Yet, the desire to show oneself and be understood through the dream is also powerful – the positive side of that initially feared exposure.

“Mutual Construction”: Teamwork Makes the Dream Work (Literally!)

The third core category, Mutual Construction, is all about experiencing dream narration as a shared process of building understanding. Trainees described how telling a dream opens up a common space for comprehension, which felt good and reassuring. What’s key here is the analyst being interested and listening attentively, rather than dishing out pre-packaged, hasty interpretations. Inquisitorial questioning, like an interrogation, was a definite no-no.

Working with dreams was also seen as a creative and playful process, with comparisons made to art or film. The dream itself is creative, and so is talking about it together. It’s like the analytic pair are interpreting an image, with both contributing their own perspectives and parts of themselves. So, it’s an active construction by both parties. This resonates with Ogden’s concept of the “analytic third,” where meaning arises in the dialogue and interaction between analyst and analysand, a co-creation.

However, this “mutual” aspect sometimes came with a question mark. Issues of “true and false” and who holds the interpretive authority (the “Deutungshoheit”) cropped up. It’s clear that dreams hold a special position for these trainees, partly due to their knowledge of psychoanalytic history and the dream’s iconic role. Case studies with prototypical dream narrations can shape an image of a “good” analysand. Telling a dream can thus become a task to be fulfilled, almost a compulsion. One person said, “I somehow have this silly image of how I am a good analysand and how I have to be in training analysis. And that, of course, includes telling dreams. As the royal road to the unconscious. … Often, I report dreams because something in me says: ‘you have to do this so that you are a good analysand, so that you cooperate well and this is interesting here, my analyst wants to hear this’.”

Freud’s “royal road” idea was often mentioned. The trainees criticized the pressure this creates, feeling compelled to tell dreams or report them in a certain way. The dream becomes loaded with significance because Freud’s theory implies you can understand something profound about the person through it. This can elevate the analyst to an all-knowing figure, making the trainee feel transparent. This “charged” nature of dream work was something both analysts (in the earlier study) and analysands critiqued, yet both also acknowledged the fascination and joy it brings.

Analyst vs. Trainee: Two Sides of the Same Dreamy Coin?

It’s interesting to compare these trainee experiences with what analysts themselves reported in that earlier Henkel et al. (2020) study. One striking similarity: dream work is a sensitive area. Analysands stressed the “highly personal” nature, the need for a solid analytic frame, and sometimes, anxiety. Analysts, too, mentioned they proceed cautiously with dreams and try to avoid quick interpretations. It seems they sense the analysand’s sensitivity and adjust accordingly.

Interestingly, dream narrations aren’t just about intimacy; they can also create a bit of distance from the content and its unconscious meaning. Trainees found it easier sometimes to share difficult stuff via dreams rather than direct confrontation. Analysts also noted this advantage, speaking of the dream as a “third thing.” So, telling dreams seems to open up a fascinating tension between intimacy and distance.

When it came to technique, analysts showed a wide range, perhaps reflecting the general diversity in analytic practice. What stood out from the trainees’ side was less talk about how dreams were interpreted or the importance of the analyst finding the “correct” content meaning. Instead, they emphasized the calming function, the shared process, and the impact on the analytic relationship – building trust, but also sometimes stirring fears. So, the “what” of dream content seemed less vital than the “how” of the work and its effect on the bond with the analyst. This experience seems to align more with object relations theories, Morgenthaler’s ideas, and the intersubjective approach, rather than a purely Freudian decoding.

The “Buts” and “What Ifs”: Looking at the Fine Print

Of course, we have to take these findings with a pinch of salt. The study itself points out limitations. The sample was small, and the inclusion criteria (training analysis on the couch) were quite specific, so we can’t generalize wildly. It’s also possible that people who particularly enjoy telling dreams were more likely to volunteer. To get a richer picture, future research could:

- Expand the circle of people interviewed.

- Talk to folks with different psychotherapeutic training backgrounds.

- Interview individuals who rarely or never tell dreams to understand why.

- Crucially, interview actual patients in therapy (not trainees) to see how their experiences compare. The role conflicts trainees face (being both analysand and candidate) likely color their experience. One trainee talked about the “balancing act” of how much to reveal as an analysand without jeopardizing their candidate role. Another wondered what the analyst made of bizarre dream images. These role conflicts even showed up in the interviews themselves, with one person asking if they should have read “The Interpretation of Dreams” beforehand!

Patients might be more uninhibited, not having these specific institutional pressures or theoretical knowledge influencing them. The historical significance of dreams in psychoanalysis definitely leaves its mark on trainees. Using audio or video recordings of actual therapy sessions could also offer deeper insights into that “mutual construction” process.

Painting the Picture: A Final Thought

The study beautifully wraps up with an anecdote. At the end of one interview, the trainee looked at a large canvas she had painted. This led to a reflection on how telling dreams in analysis is similar: dreaming brings something to a “canvas.” But to visualize ideas, you need paint, a surface to hold it, and a frame. The interviews made it clear that a stable foundation (the analytic framework) is vital for dream telling. On that base, something about the narrator can become visible. And unlocking the meaning of what’s become visible happens in dialogue, constructed together.

So, next time you’re pondering a peculiar dream, remember it’s not just a random jumble. And for those in the unique position of training analysis, sharing these nightly creations is a complex, rich, and deeply personal journey of discovery – for both people in the room.

Source: Springer