Unlocking Early Liver Cancer Detection: The Methylation Story

The Big Challenge: Catching HCC Early

Hey there! Let’s talk about something serious but super important: liver cancer, specifically Hepatocellular Carcinoma, or HCC. It’s a tough one, and honestly, a big reason it’s so deadly is that we often find it when it’s already quite advanced. Imagine trying to put out a fire that’s already engulfed the whole building instead of just a small flame – much harder, right? That’s why finding better ways to spot HCC early, before it gets too big or spreads, is absolutely crucial. We need non-invasive methods that can act like an early warning system.

Our Deep Dive into DNA ‘Sticky Notes’

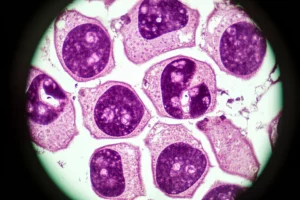

So, what if we could look at tiny molecular changes happening in our bodies that signal cancer is starting? That’s where DNA methylation comes in. Think of DNA like a recipe book for your body. Methylation is like adding little ‘sticky notes’ to certain pages. These notes don’t change the recipe itself (the DNA sequence), but they can change *how* the recipe is read or used. In cancer, these sticky notes often get messed up – they appear in the wrong places or disappear from where they should be. We call these specific changes DNA Methylation Markers (DMMs).

Our team got together and thought, “Could these methylation changes be the early warning system we need for HCC?” To figure this out, we embarked on a pretty extensive study. We gathered samples – a total of 385, which is quite a number! These came from both liver tissues (because that’s where the cancer grows) and blood (because a simple blood test would be fantastic for screening!).

We used a cutting-edge technique called Genome-Wide Methylated DNA sequencing, or MeD-seq. This lets us look at methylation patterns across a huge chunk of the entire genome, giving us a really detailed picture. We started by analyzing 46 liver tissues with MeD-seq to find potential markers. Then, we validated the most promising ones using a more targeted method called quantitative methylation-specific PCR (qMSP) on a larger set of 175 liver tissues. The real test, though, was seeing if these markers worked in blood. We evaluated them in 180 blood samples, even doing MeD-seq on some blood samples to double-check our findings.

What We Found in Liver Tissue: A Clear Signal

In the liver tissues, MeD-seq showed us something really clear: there were a *lot* of regions where the methylation patterns were different between HCC tissues and non-HCC controls. It was like seeing a distinct fingerprint for cancer in the liver’s DNA sticky notes. When we used qMSP to zoom in on the top 11 markers we identified, they performed really well. Especially in telling the difference between cirrhotic HCC (HCC that developed in a liver with cirrhosis, which is very common) and just cirrhosis alone. Some of these markers had impressive accuracy, with AUC values (a measure of how well a test distinguishes between groups) going up to 0.957. This told us these markers are definitely linked to HCC when you look directly at the tumor tissue.

We also noticed that the methylation changes were strongly associated with the presence of HCC itself, rather than just the underlying cirrhosis. This was a key finding in the tissue analysis – the cancer was driving these specific methylation patterns in the liver.

The Puzzle in the Blood: A Fainter Signal

Now, for the big question: did these promising markers work in blood? This is where things got a bit more complicated. When we tested the top 5 markers in blood samples, their performance for detecting *early-stage* HCC wasn’t as strong. In our initial group of samples, the sensitivity (how often the test correctly identifies someone with early HCC) ranged from only 26.7% to 43.3% at a good specificity (how often it correctly identifies someone *without* HCC). That’s not quite the early warning system we were hoping for.

We also tried combining our methylation markers with existing risk scores like the ASAP/GAAD score, which uses things like AFP and PIVKA-II (other blood markers). Adding our DMMs did increase the sensitivity a bit, but only by about 5.4% in our validation group compared to using the ASAP/GAAD score alone. It helped more for late-stage HCC, but our focus was on catching it *early*.

Why Blood is Tricky for Early HCC

So, why the difference between tissue and blood? We think there are a couple of main reasons. First, HCC often develops in livers that are already damaged by cirrhosis. Cirrhosis itself causes changes in DNA methylation, not just in the liver, but potentially in the blood too. This creates a kind of ‘noisy’ background that makes it harder to spot the specific methylation signals coming from a small, early-stage tumor.

Second, the amount of DNA from the tumor that makes it into the bloodstream (called cell-free DNA, or cfDNA) is likely very low in early-stage HCC. Most of the cfDNA in a cirrhotic patient’s blood comes from other cells. It’s like trying to find a few grains of sand from a specific beach mixed into a whole truckload of sand from many different places.

Our MeD-seq analysis on blood samples really hammered this point home. We didn’t find any significant differences in methylation patterns between cirrhotic HCC patients and cirrhotic controls using this genome-wide approach. However, both of these groups showed *very* different methylation patterns compared to healthy individuals. This highlights a crucial point: when looking for early HCC biomarkers in blood, the right comparison group isn’t healthy people, but people *with cirrhosis*, as cirrhosis already alters the landscape.

The Takeaway: Promising, but Not a Magic Bullet… Yet

What does this all mean? Our study confirms that DNA methylation changes are definitely a hallmark of HCC in liver tissue, and some markers look very promising there. However, translating that promise to a simple blood test for *early-stage* HCC detection in patients with cirrhosis is challenging. The high background methylation from cirrhosis and the low amount of tumor DNA in blood seem to dilute the signal.

Combining methylation markers with existing tests like ASAP/GAAD did offer a slight improvement, but perhaps not enough to justify the increased complexity and cost just yet, especially for early detection. This doesn’t mean methylation markers are out of the picture entirely for HCC surveillance, but it tells us we need smarter ways to use them in blood, perhaps by focusing on different types of markers or developing more sensitive detection methods that can specifically pick up the low levels of tumor DNA against the noisy background of cirrhosis-related changes.

We learned a ton from this deep dive, and it helps us understand the complexities of using non-invasive biomarkers for HCC in high-risk populations. The journey to finding the perfect early warning system continues!

Source: Springer