Unlocking the Sex-Specific Secrets of an Autism Gene: DDX3X

Hey there! Let’s dive into something truly fascinating that scientists are uncovering about how our brains are built, and how sometimes, things can go a little sideways in a way that seems to affect girls more than boys. We’re talking about a gene called DDX3X.

You might have heard about autism spectrum disorder (ASD) or intellectual disability (ID). They’re complex conditions, and while we’ve learned a lot, there’s still so much we don’t understand. One puzzling piece is that ASD, in particular, is diagnosed much more often in males. But then you encounter something like DDX3X syndrome, which is a leading genetic cause of ID and ASD, and guess what? Over 95% of the individuals identified with mutations in this gene are female! This immediately tells us that studying DDX3X offers a unique window into the *sex differences* in how the brain develops.

Meet DDX3X: More Than Just a Gene

So, what exactly is DDX3X? Think of it as a tiny, busy worker inside our cells. It’s an RNA helicase, which means it’s involved in all sorts of crucial jobs related to RNA – the molecule that carries instructions from our DNA to build proteins. DDX3X is particularly important for things like translating those RNA messages into proteins and managing these little cellular compartments called condensates and granules.

Now, here’s a neat trick DDX3X has: it’s located on the X chromosome, but unlike most genes on the X chromosome in females, it *escapes* X chromosome inactivation. This means females typically have two active copies of DDX3X (one from each X chromosome), while males have just one (from their single X). This difference in “dosage” – having one copy versus two – is a big deal and likely plays a role in why mutations affect the sexes differently. Males *do* have a Y chromosome counterpart, DDX3Y, but it seems DDX3Y isn’t quite the same and can’t fully compensate for DDX3X’s job in the brain.

Mutations in DDX3X are often *de novo* in females, meaning they pop up spontaneously and lead to having only one working copy (haploinsufficiency) or sometimes no working copies at all. In the rare cases seen in males, the mutations are usually less severe and inherited. This difference in the *type* and *dosage* of mutations between sexes is key to understanding DDX3X syndrome.

Building the Brain, Differently

The brain is incredibly complex, and its development is a carefully orchestrated process. This study really dug into how DDX3X mutations mess with this process, looking at neurons – the brain’s core communication cells – both in lab dishes and in mouse models.

One of the first things they examined was how neurons grow their “branches,” called dendrites. Dendrites are like antennae that receive signals from other neurons. What they found was pretty striking: losing DDX3X made dendritic structures simpler. But here’s the kicker – this effect was dependent on both the *amount* of DDX3X missing (dosage) and the *sex* of the neuron. Female neurons with one or two bad copies showed issues, while male neurons with no good copies also had problems, but the specifics differed slightly between the sexes and dosages. It suggests DDX3Y in males might offer some limited help, but not enough to fully prevent problems.

They even checked this *in vivo* in mouse brains, focusing on neurons in the motor cortex (a brain area important for movement). They saw that even having just one working copy of DDX3X (haploinsufficiency), like in affected females, altered the shape of these motor neurons’ dendrites, particularly the parts reaching towards other brain layers. This is super relevant because individuals with DDX3X syndrome often have motor difficulties.

The Tiny Spikes: Dendritic Spines

Beyond the main branches, dendrites are covered in tiny protrusions called dendritic spines. These are where most synapses – the connections between neurons – are located. The study looked at how DDX3X affects spine development, making sure to isolate this process from the earlier dendritic growth phase.

And wow, did they find a sex-specific effect here! DDX3X seemed absolutely essential for proper spine formation and maturation, but *only* in female neurons. Male neurons, whether they had a working DDX3X copy or not, didn’t show the same spine problems. In female neurons, having no working DDX3X copies led to *too many* spines in certain areas, while having just one working copy (haploinsufficiency) affected the *shape* of the spines, making some look more mature (“mushroom-like”) or elongated (“long thin”).

This suggests a really nuanced role for DDX3X in females: having enough (two copies) helps keep spine numbers in check and ensures proper maturation, while having too little (one or zero copies) throws things off in different ways.

The Protein Puzzle: What’s Happening Inside?

To figure out *how* DDX3X is doing all this, they looked at the proteins present in these neurons using a technique called proteomics. Comparing female and male neurons first, they confirmed that many proteins are expressed differently between the sexes, and DDX3X itself was one of the most prominent examples, being higher in females.

Intriguingly, the proteins that were higher in female neurons were heavily involved in things like RNA processing and, crucially, *mRNA translation* – the process of building proteins from RNA instructions.

Then they looked at what happens when DDX3X is deficient. In female neurons with reduced DDX3X, many of these same proteins involved in protein synthesis were *downregulated*. It was like a mirror image! Proteins that are normally higher in females were reduced when DDX3X was reduced. This included many components of the cellular machinery that builds proteins, like ribosomal proteins.

In male neurons lacking DDX3X, the protein changes were different and didn’t show this widespread impact on the protein synthesis machinery. This points to distinct molecular pathways being affected by DDX3X loss in males versus females.

Tiny Factories: Ribosomes and Nucleoli

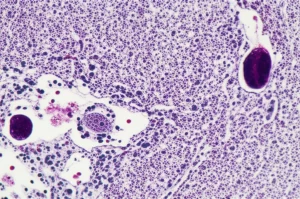

Since the protein analysis pointed strongly towards protein synthesis issues, they investigated further, looking at ribosomes (the cellular factories that build proteins) and nucleoli (structures within the nucleus where ribosomes are assembled).

They found that female neurons, particularly a specific type in the motor cortex (called CTIP2+ neurons), had a different distribution of ribosomal RNA (rRNA) compared to males, suggesting differences in how ribosomes are processed or exported. This female bias seemed to *require* having two working copies of DDX3X, as it was lost in females with only one copy, making them look more like males in this regard.

Furthermore, these specific female neurons also had larger nucleoli and a higher total nucleolar volume than male neurons. Again, this difference disappeared in female neurons with reduced DDX3X. This strongly suggests that DDX3X, at full dosage, helps drive a female-specific signature in ribosome biogenesis and nucleolar properties.

DDX3X vs. DDX3Y: A Tale of Two Genes

Remember DDX3Y, the Y chromosome counterpart? The researchers wanted to see if DDX3Y could do the same jobs as DDX3X. They put human versions of DDX3X or DDX3Y into female neurons that were deficient in mouse DDX3X.

Turns out, both human DDX3X and DDX3Y could help rescue the dendritic growth problems. This suggests some overlapping function. However, they had different effects on the nucleoli. Expressing human DDX3X led to smaller nucleoli (bringing them back towards a control state), while human DDX3Y didn’t have the same effect on nucleoli number. This supports the idea that while they share some functions, DDX3X and DDX3Y are *not* fully redundant and have distinct roles, particularly in regulating nucleolar dynamics. This also aligns with previous work showing they have different properties related to how they form these cellular compartments (like nucleoli) through a process called phase separation.

Importantly, they showed that DDX3X’s ability to fix these neuronal structure and nucleolar issues required its enzymatic activity (its ability to work with RNA), as a mutant version that couldn’t do this job had no effect.

Putting it Together: Behavior

Okay, so DDX3X affects neuronal structure and molecular processes in a sex-specific way. Does this translate to behavior? They used a mouse model where DDX3X was specifically removed from forebrain neurons (the area most affected in humans).

They found that both female mice with one copy of DDX3X removed (haploinsufficient) and male mice with DDX3X removed from the forebrain showed motor deficits. This included reduced grip strength and poorer performance on tests of balance and coordination, like walking on a beam or staying on a rotating rod.

Interestingly, while both sexes were affected, there were nuances. For example, control female mice were generally better at some motor tasks than control males (perhaps due to weight differences), but this female advantage was *lost* in the DDX3X mutant females. This behavioral data in a forebrain-specific model supports the idea that DDX3X deficiency in this brain region is enough to cause motor problems, and that the sex-specific cellular findings have real-world consequences for how these mice move and coordinate.

Why This Matters

So, what’s the big takeaway from all this? This study provides really strong evidence that DDX3X is a key player in shaping the differences between male and female brains during development.

- First, it helps establish a *female-biased signature* in neurons related to building ribosomes and making proteins, and shows that having two working copies of DDX3X is needed for this signature.

- Second, it reveals that DDX3X is essential for the development of dendritic spines, but *only* in female neurons.

- Third, it links these cellular and molecular findings to behavioral outcomes, showing that DDX3X deficiency in the forebrain leads to motor issues, with sex-specific patterns.

It’s clear that the balance between DDX3X and DDX3Y, and their potentially different functions, is crucial. While DDX3Y might offer some limited help, it can’t fully step in for DDX3X, explaining why severe mutations in DDX3X are so devastating, even in males (though they are rare).

These findings are super important for understanding DDX3X syndrome and neurodevelopmental disorders in general. They highlight that we can’t just study these conditions as if they affect everyone the same way; sex differences are real and are rooted in specific molecular and cellular pathways. Knowing that DDX3X is involved in ribosome biogenesis and nucleoli links DDX3X syndrome to a growing group of genetic disorders affecting these fundamental cellular processes.

Plus, the fact that DDX3X is needed for spine development *after* the initial brain building phase (postnatally) is potentially good news. It means there might be a window later in development where therapies could intervene to help fix some of these problems. Scientists are already exploring whether restoring gene function later in life can help with other ASD-related genes, and this study adds DDX3X to the list of exciting possibilities.

It’s a complex picture, but one that brings us closer to understanding the intricate ways our brains are wired and how we might help those affected by conditions like DDX3X syndrome.

Source: Springer