Unlocking Super Strength: Cryogenic Cycling for Magnesium Alloys

Hey there! Let me tell you about something pretty cool we’ve been looking into. You know Magnesium (Mg) alloy, right? It’s often called the “lightest metal material” of our time. Think lightweight design, saving energy, being kinder to the environment – Mg alloys are key players in fields like electronics, aerospace, and transportation. It’s pretty amazing stuff!

But, and there’s always a ‘but’, Mg alloy isn’t perfect. It has a bit of a reputation for having low absolute strength and being a bit tricky to work with. Its structure, called hexagonal close-packed, means it’s not exactly known for being super bendy or ductile. These limitations can sometimes hold it back from reaching its full potential in certain applications.

So, what do we do? Well, folks are always trying to make it better. Some researchers mess around with the recipe, adding different elements to improve things. Others look at new ways to process the material after it’s made. And that’s where our story really gets interesting.

Enter the Cold Treatment Hero

We’ve been exploring a processing technique called Cryogenic Cycling Treatment (CCT). Now, CCT isn’t brand new; it’s been used on other metal materials with some interesting results. We’ve seen it improve things like fracture toughness or reduce residual stress in different alloys. But its effect on Magnesium alloys, specifically how it changes their guts (the microstructure) and boosts their performance, hasn’t been fully understood. And that’s a gap we really wanted to fill, especially for a promising alloy like Mg-4.5Al-2.5Zn, which needs a little extra oomph to expand its uses.

Our Little Experiment

So, here’s what we did. We took some hot-rolled sheets of Mg-4.5Al-2.5Zn alloy. We then put them through the CCT process, cycling them between really cold temperatures (cryogenic) and air cooling. We tried different numbers of cycles – from one all the way up to five – and also had a control group that was just air-cooled after rolling.

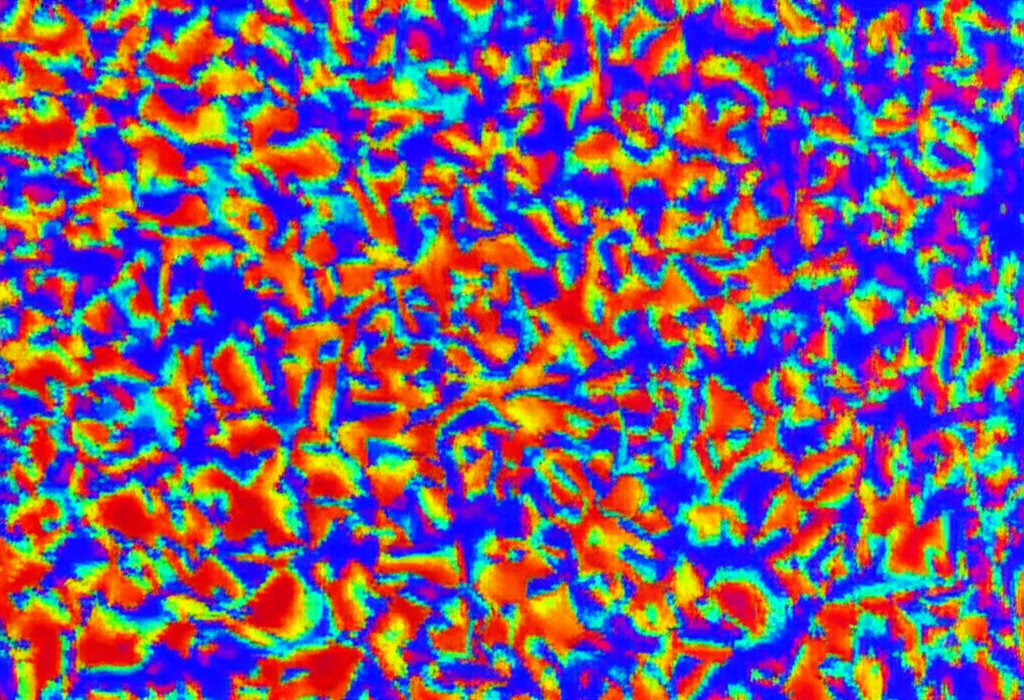

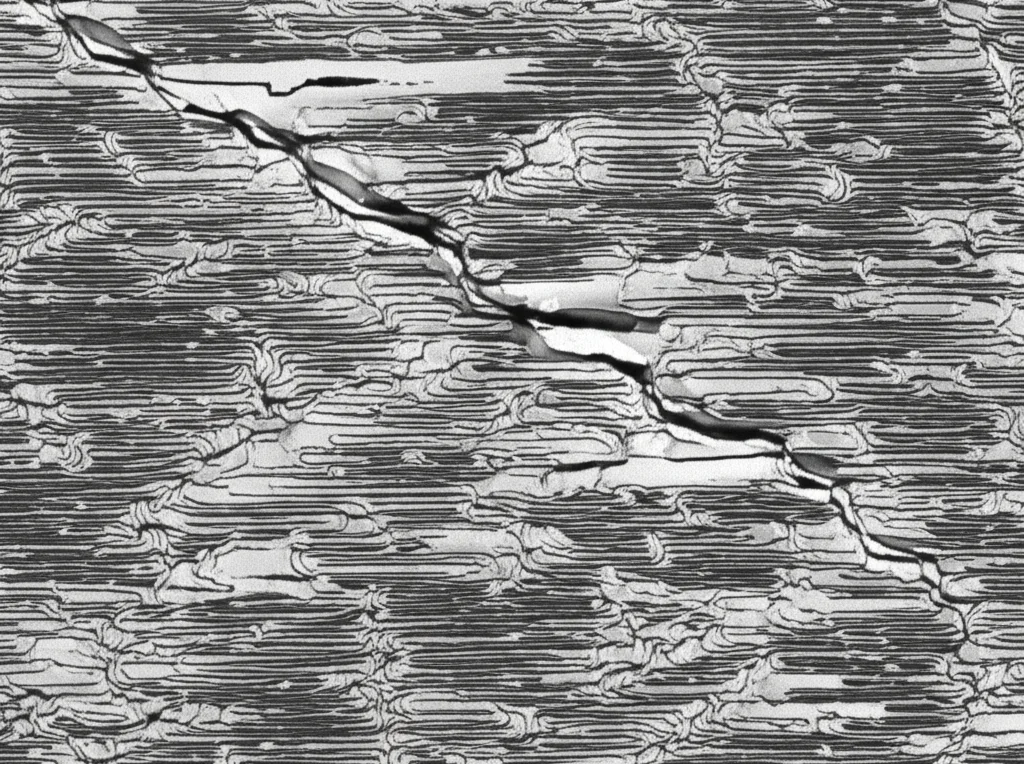

After the treatment, we put these samples through the wringer. We did tensile tests to see how strong and how ductile they were. We also peered deep inside using fancy tools like optical microscopy (OM), electron back-scatter diffraction (EBSD), and transmission electron microscopy (TEM). These tools let us see the grains, the dislocations (tiny defects in the crystal structure), and other features that make up the material’s internal landscape. We wanted to understand how the CCT changed this landscape and how those changes affected the strength and ductility we measured.

The Exciting Results!

And boy, did we find something! The samples that got the CCT were significantly better than the one that was just air-cooled. It was like giving the alloy a superhero boost!

What was really fascinating was how the number of cycles mattered. We saw that the sample treated with 3 cycles showed the highest ductility, stretching nicely up to about 18.6%. But if you were looking for pure muscle, the 4-cycle sample was the champion, showing the highest strength at around 311.8 MPa. This 4-cycle sample really hit the sweet spot, showing great strength *and* impressive ductility (17.8%), a nice bump up from the air-cooled sample.

Even the 5-cycle sample, while not quite hitting the peak of the 4-cycle one, was still better than the untreated sample. It seems there’s an optimal number of cycles to get the best performance, which is something we’ve seen in other materials too.

Peeking Inside: The Microstructure Story

So, why did this happen? Our microscopy work gave us some great clues. It all comes down to how the CCT changes the material’s internal structure:

- Fine Grains: While the average grain size didn’t change drastically across all CCT samples, we saw that the 4-cycle sample, in particular, had a more uniform and finer grain structure compared to the air-cooled one. Finer grains mean more grain boundaries, and these boundaries are great at blocking the movement of dislocations, which helps increase strength (that’s called grain boundary strengthening!).

- Dislocations Galore: CCT introduces a high density of dislocations. Think of these as tiny traffic jams inside the metal. More traffic jams make it harder for the material to deform, increasing strength. The 4-cycle sample had the highest dislocation density, lining up nicely with its peak strength.

- Low-Angle Grain Boundaries (LAGBs): These are like smaller, less disruptive boundaries within the grains, formed by rearranged dislocations. We found a higher fraction of LAGBs in the CCT samples, especially the 4-cycle and 5-cycle ones. LAGBs also help hinder dislocation movement, adding to the strengthening effect.

- Precipitates: We observed the formation of Mg17Al12 phases, which are tiny particles scattered within the material. These precipitates act like obstacles, pinning dislocations and preventing them from moving easily. This “precipitation strengthening” is another big reason for the improved strength. They also seem to help refine the grain structure.

- Texture Evolution: The CCT process also changed the preferred orientation of the grains (the texture). The 4-cycle sample had a strong, centrally focused texture. This texture, combined with the activation of different slip systems (the ways the crystal can slide and deform), particularly the non-basal ones, is crucial for improving both strength and ductility in Mg alloys.

The Dance of Microstructure and Properties

It’s really a complex dance between all these factors. The CCT introduces internal stress variations through the temperature changes. These stresses encourage the formation and rearrangement of dislocations, leading to higher dislocation density and LAGBs. The rapid cooling also suppresses certain processes like static recrystallization that might reduce these features. Simultaneously, CCT seems to promote the precipitation of strengthening phases like Mg17Al12.

The combined effect of finer grains, a high density of dislocations and LAGBs blocking their movement, precipitates pinning them down, and a favorable texture that encourages multiple slip systems to activate (not just the easy ones), all contribute to the significant boost in mechanical properties we observed. The 4-cycle treatment seemed to hit the sweet spot where these beneficial microstructural features were optimally developed, giving us that great balance of strength and ductility.

Different numbers of cycles led to different degrees of internal stress changes, which in turn affected the LAGB fraction, the texture development, and which slip systems were most easily activated. That’s why we saw the properties peak at 4 cycles and then start to change again at 5 cycles – the microstructure was still evolving with each thermal shock.

The Big Picture

So, what’s the takeaway? We’ve shown that cryogenic cycling treatment is a seriously effective way to improve the mechanical properties of rolled Mg-4.5Al-2.5Zn alloy sheets. It’s not just a little tweak; it makes a significant difference compared to standard processing.

By carefully controlling the number of cycles, we can tailor the properties, achieving either peak ductility (like with 3 cycles) or peak strength and a great overall balance (like with 4 cycles). This improvement is thanks to a whole host of microstructural changes – refining grains, piling up dislocations, creating LAGBs, growing strengthening precipitates, and tweaking the texture.

Understanding these mechanisms gives us a solid foundation for future research and, more importantly, provides a practical new method for preparing high-performance Magnesium alloys. This could really help expand where we can use these lightweight materials, making everything from planes to phones lighter and more efficient. Pretty cool, right?

Source: Springer