Cracking the Code: Can Skull Sutures Really Tell Age?

Hey there! Ever wondered how forensic scientists figure out how old someone was when they died, especially if there’s not much left? It’s a crucial part of identifying remains and building that “biological profile” – you know, figuring out sex, ancestry, height, and age. When we’re dealing with adult remains, we often look for signs of wear and tear, those age-related changes that happen over time.

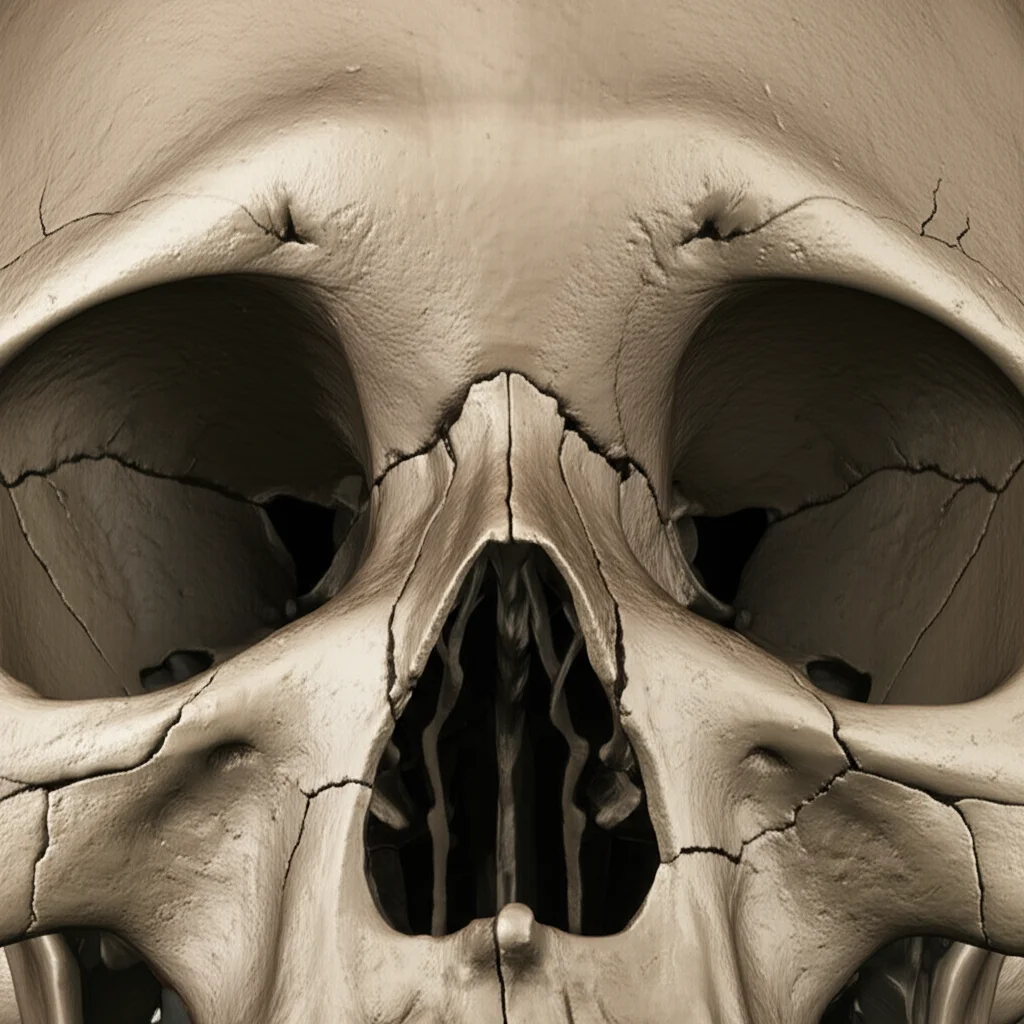

One method that’s been around for ages, literally, involves looking at the seams in your skull – the cranial sutures. These are those wiggly lines where the different plates of your skull fused together as you grew. The idea is that they close up, or “obliterate,” over time, giving us a clue about age. Sounds simple, right? Well, as with many things in science, it’s a bit more complicated, and honestly, it’s one of the most controversial methods out there.

Why the Controversy?

The traditional way to assess cranial sutures is just by looking at them, either on the outside (ectocranial) or inside (endocranial) of the skull. You check how much of the suture has fused together. The problem is, people are different! The rate at which these sutures close varies *a lot* from person to person. This individual variability makes it tough to give a definitive age estimate based on sutures alone.

Despite this uncertainty, it’s still a popular method, partly because the skull is often one of the best-preserved parts of a skeleton. So, even if other bones are damaged or missing, you might still have a skull to work with.

Enter Modern Technology: PMCT

Now, things have gotten a bit more high-tech. Instead of just peering at a dry skull, we can use imaging techniques. X-rays were an early step, but since the late 70s, computed tomography (CT) has become a game-changer. CT scans let us see *through* the bone, giving us a much more detailed look at what’s happening inside.

Using postmortem computed tomography (PMCT) before a traditional autopsy is becoming standard practice in many places. It’s great for creating digital archives, sharing data with colleagues, and even making 3D prints for court. Plus, it’s super useful in anthropology for studying both ancient and modern bones without damaging them.

Modern CT allows for incredibly detailed assessments of those tricky cranial sutures. Studies have shown that analyzing sutures via CT gives results pretty similar to looking at them directly, which is cool.

Our Study: A Deep Dive with PMCT

So, we wanted to really dig into this and see if assessing cranial suture closure using PMCT could be a reliable way to estimate age at death in a forensic context. We looked at PMCT scans of 114 male skulls from Polish individuals. Why only men? Well, unfortunately, forensic autopsies involve men much more frequently, making it hard to get a large, representative group of women across all age ranges for this kind of study. We hope future, larger studies can include more diverse groups!

We were pretty strict about who we included. We needed individuals with:

- Known date of birth (from ID) and death (from postmortem request).

- No skull damage from the cause of death.

- No history of cranial surgery or injury.

- Body recovered within two days of death.

We had to exclude cases like bodies from water, fire victims, or those with advanced decomposition, as these can affect the skull’s condition.

We used some fancy software to analyze the scans. We looked at the coronal, sagittal, and lambdoid sutures – the main ones people usually study. We used a scale to score the extent of suture closure, both on the outer (ectocranial) and inner (endocranial) surfaces, and also looked at cross-sections using multiplanar reconstruction (MPR). This let us see if there were gaps between the bones or within the suture line itself.

We had a detailed scale for suture obliteration, ranging from “No Obliteration” (gap visible) to “Complete Obliteration” (suture line gone). We also noted different “suture variations” based on where the gap was present (external table, internal table, all the way through, etc.). Assigning numbers to these stages helped us crunch the data statistically.

We used statistical tests to see if there was a significant relationship between age and the stage of suture closure in different parts of the sutures. We were particularly interested in whether different stages of closure corresponded to significantly different average ages.

What We Found: A Mixed Bag

Our analysis using MPR (looking at cross-sections) seemed to offer more potentially useful insights for age estimation compared to just looking at the surfaces with VRT (volume rendering technique). However, even with MPR, only a handful of specific suture segments and obliteration stages showed a statistically significant mean age difference of 10 years or more between stages.

For example, in the coronal suture (C1 segment) on the right side, there was a significant age difference between stages 0 (no obliteration) and 3 (suture gap extending across the whole thickness). This stage 3, where the gap goes all the way through, actually seemed pretty important, appearing in most of the pairs that showed a large age difference. It’s also something that’s quite clear to see on a radiological image.

Looking at the outer and inner surfaces (VRT analysis), we found that closure happens at different rates on the inside versus the outside for most sutures. More potentially useful segments for distinguishing “younger” from “older” were found on the inner surface, but only slightly more than on the outer.

Interestingly, some suture parts, like certain segments of the lambdoid suture and parts of the coronal suture, showed *no* significant relationship with age at all in our study. This means you simply can’t use those specific spots to guess someone’s age.

One key takeaway was that while some segments *did* show a relationship with age, the differences in mean age between stages were often not huge, or the stages themselves weren’t consistently linked to specific age ranges.

The Bottom Line: Not a Perfect Clock

So, after all that detailed analysis, what’s the verdict? Our study on this group of Polish men using PMCT confirmed what many others have suspected: using cranial suture closure alone isn’t the most accurate way to pinpoint age at death. It’s not like a perfect clock ticking away predictably.

At best, this method seems useful for making broad distinctions, like telling if someone was “younger” versus “older,” perhaps separating individuals around 30-35 from those over 50. While this can be helpful in some forensic scenarios, it’s often not precise enough for definitive identification or age estimation needs.

Why isn’t it more predictable? Well, science suggests it’s not just about age. Factors like genetics (a specific gene polymorphism, MSX1, has been suggested), chronic metabolic diseases (like rickets in children, though less clear in adults), and even mechanical stress on the skull might play a role in how and when sutures close. Some researchers even argue that closure happens independently of age or disease!

Despite these limitations, PMCT is definitely a valuable tool for visualizing the sutures in detail. It allows us to see things we might miss with just a direct look. Using consistent CT parameters is important for accurate interpretation.

Our findings align with other studies that conclude cranial sutures shouldn’t be used as a standalone method for precise age estimation. However, they might still be useful:

- In combination with other age estimation methods (like looking at ribs, pelvis, or clavicle).

- When other parts of the skeleton aren’t available.

- As a preliminary step to get a general idea (“younger/older”) before applying more precise techniques.

Ultimately, while PMCT gives us an incredible view inside the skull, the wobbly nature of suture closure means they are more of a general guide than a precise age marker in forensic investigations. It’s a fascinating area, but definitely one where we need to be cautious about how we interpret the findings!

Source: Springer