Saving History from the Sky: Rain’s Impact on Coral Limestone

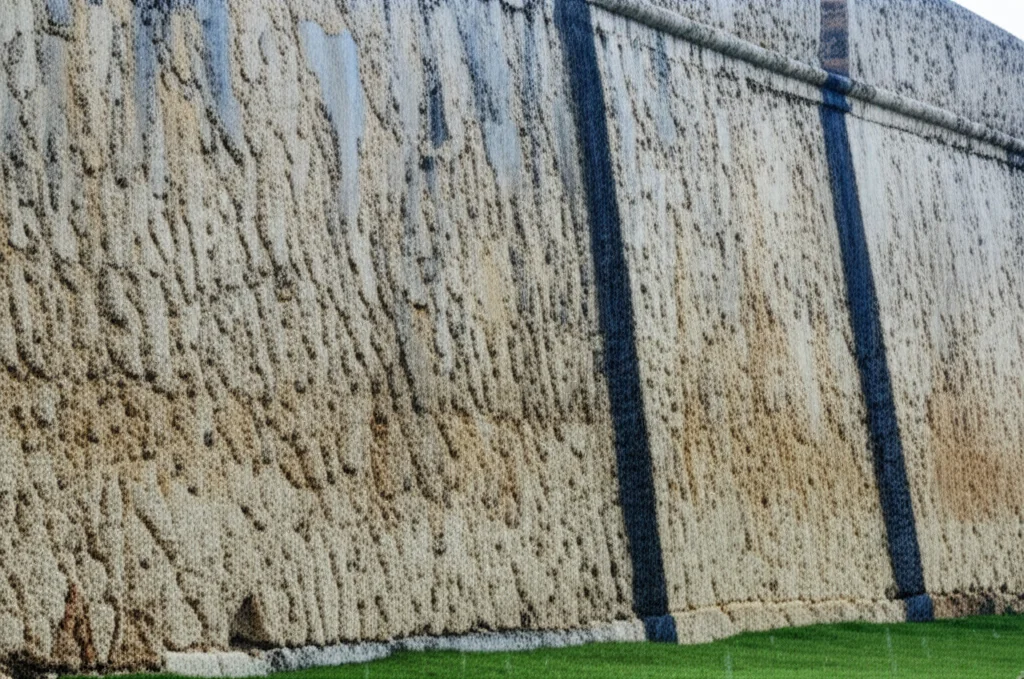

Hey there! Ever walked past an old building, maybe near the coast, and just felt the history radiating from its walls? If those walls were built with coral limestone, you’re looking at something pretty special. This stuff isn’t just rock; it’s the solidified legacy of ancient coral reefs, a building material used for centuries in places all over the world, from the Mediterranean shores to tropical islands.

But here’s the thing: even something as solid as stone isn’t immune to the elements. And one of the biggest culprits when it comes to wear and tear? Good old rain. Yep, that seemingly harmless wet stuff falling from the sky can pack a punch, especially when it comes to porous materials like coral limestone. It’s like a slow, persistent attack on history itself.

That’s why I found this research particularly fascinating. It dives deep into how wet atmospheric deposition – basically, rain and whatever’s dissolved or suspended in it – messes with coral limestone. They took a close look at a specific type from Veracruz, Mexico, called múcara stone, to figure out exactly what’s happening and, more importantly, how to predict the damage. Pretty neat, right? It’s all about conservation, making sure these incredible structures stick around for generations to come.

Why Coral Limestone is a Big Deal (and Why We Need to Protect It)

So, why is coral limestone so important? Well, first off, it’s literally built by tiny sea creatures – corals! They create calcium carbonate (CaCO₃), which over time, gets cemented together into stone. This process, called lithification, is vital for building and stabilizing coral reefs, which are super important ecosystems bursting with life.

Because it’s relatively easy to cut and carve, people have used this stone for ages. Think ancient fortresses, beautiful mosques, and historical buildings across tropical and subtropical regions. It’s a material deeply woven into the cultural fabric of many coastal communities. But unlike quarrying other rocks, harvesting coral limestone directly impacts living reefs, which is a big no-no these days due to environmental protection laws. This means the stone in existing buildings is often irreplaceable. Protecting what’s already built is absolutely crucial.

The Rain Problem: More Than Just Getting Wet

Okay, back to the rain. It’s not just the water itself that’s the issue, although water is a major player in stone decay. Rain acts as a delivery system for whatever pollutants are floating around in the atmosphere – things like aerosols, particles, and gases. When rain hits the stone, these substances interact with the material, kicking off chemical reactions.

For calcium carbonate stones like coral limestone, the main problem is dissolution. The stone literally starts to dissolve. You might think it’s a simple process, but it’s actually a complex dance of chemical equilibria, heavily influenced by the rain’s pH (how acidic it is). Acid rain, as you’ve probably heard, is particularly bad because the extra acidity really speeds up the dissolution of the CaCO₃ matrix.

The researchers point out that it’s not just about the acidity, though. The sheer *volume* of rain matters a lot too. More rain means more interaction, more opportunity for those chemical reactions to happen, and more material washing away. They also highlight the role of bicarbonate (HCO₃⁻) in the process, which is formed when CaCO₃ dissolves. This dissolved stuff can then move around inside the stone and potentially re-precipitate as CaCO₃ elsewhere, which can cause internal stress or block up the pores. It’s a complicated picture!

Putting the Stone to the Test: The Veracruz Study

To get a real handle on this, the researchers focused on múcara stone from Veracruz, a historic port city in Mexico with a tropical climate. They basically did two things:

- Outdoor Exposure: They placed samples of the stone outside in Veracruz for two years, letting the real rain do its thing.

- Accelerated Weathering: They also put samples in a special lab chamber and blasted them with artificial rain designed to mimic the composition of the rain collected in Veracruz. They even made different batches of artificial rain – ‘global’ (all rain), ‘acid’ (pH elt; 5.6), and ‘no acid’ (pH ≥ 5.6) – to see the different effects.

They monitored the stone samples closely, looking at things like mass change, water absorption capacity (WAC), and open porosity (OP). They also analyzed the “lixiviates” – the liquid that dripped off the stone after the artificial rain hit it – using a technique called Ion Chromatography (IC). Analyzing what came *out* of the stone helped them figure out what was happening *inside*.

What Did They Discover? The Decay Story Unfolds

So, what were the big takeaways from all this testing?

Monitoring Decay: Mass Matters Most

Turns out, measuring the stone’s mass was the most reliable way to track decay. They saw a significant mass loss in the samples exposed to artificial rain, confirming that múcara stone is indeed vulnerable to wet atmospheric deposition, regardless of whether the rain is acidic or not. Interestingly, the samples exposed to the total ‘global’ rain volume showed the most severe mass loss overall, even though the ‘acid’ rain was more harmful *per liter*. This really highlights the importance of the total rain volume.

What about WAC and OP? While you might expect a porous stone to absorb more water as it decays, these measurements didn’t show significant changes and weren’t great indicators for *in situ* monitoring. The researchers suggest this might be because non-soluble stuff inside the stone moves around or clay minerals swell, potentially blocking up the pores.

The Chemistry Confirmed: Dissolution is Key

Analyzing the lixiviates with IC was super insightful. They saw an increase in ions like calcium (Ca²⁺) and bicarbonate (HCO₃⁻) in the liquid that came off the stone compared to the rain that went on. This is solid evidence that the CaCO₃ matrix of the stone was dissolving. The carbonate equilibria system – the balance between carbonate, bicarbonate, and carbonic acid – is definitely controlling this process.

They also found signs of salt recrystallization happening inside the stone, mainly sodium chloride (NaCl) from marine aerosols. While coral limestone’s pore structure makes it somewhat resistant to the typical damage caused by salt crystallization, it’s another phenomenon occurring within the material.

And pollution? The study area in Veracruz showed that sulfate (SO₄²⁻) was the main culprit behind acid rain, likely coming from SO₂ emissions, possibly linked to port activity and oil platforms. This reinforces the idea that local environmental conditions, especially pollution, play a significant role in heritage decay.

Predicting the Future: Damage Functions

One of the coolest outcomes of this research is the development of damage functions. These are basically mathematical equations that relate the volume of rain hitting the stone to the amount of mass loss (decay). Instead of just saying “acid rain is bad,” these functions give conservationists and urban planners a tool to *quantify* the potential damage based on rainfall data.

The functions developed in this study, based on rain volume rather than just time, are particularly useful. They can account for variations in yearly rainfall (droughts vs. rainy years) and, importantly, can be applied to other coral limestone sites around the world, especially in tropical climates like the one in Veracruz. This means the findings from one study site can help protect heritage in many other places facing similar environmental threats.

Lab vs. Real World: How Did the Models Stack Up?

Comparing the results from the accelerated lab tests with the real-world outdoor exposure was the ultimate test for their damage functions. And guess what? The equations performed pretty well! The predicted mass loss from the models was very close to the actual mass loss observed in the specimens left outside, with differences usually less than 3%. This gives us confidence that these models are a reliable tool for estimating decay.

Why This Matters for Saving Our Shared Heritage

So, why go through all this trouble studying rainy rocks? It boils down to preserving our cultural heritage. Buildings made of coral limestone are unique historical assets. Because the stone is no longer easily or ethically sourced, protecting the existing structures is paramount. Understanding *how* and *why* they decay allows us to develop better conservation strategies.

This research tells us that focusing on the volume and acidity of rain is key. It highlights the need to monitor atmospheric conditions, especially in areas with significant sources of pollution like busy ports. By using tools like the damage functions developed here, authorities and conservationists can assess the vulnerability of coral limestone buildings, prioritize conservation efforts, and even inform urban planning decisions to mitigate environmental impacts.

It’s a reminder that the health of our environment is directly linked to the preservation of our history. By understanding the subtle, persistent ways nature interacts with the materials we build with, we can take smarter steps to protect the incredible legacies left behind by past generations.

Source: Springer