Jaw-Dropping News: What *Really* Happens When Your Condylar Fracture Heals the “Easy” Way?

Alright, folks, let’s chat about something that might make you grit your teeth a little – a broken jaw. Specifically, we’re diving into what happens with a condylar head fracture (CHF). That’s the knobby bit at the top of your lower jaw that forms part of your jaw joint. When it breaks, it’s no small matter, affecting everything from your smile to how you chew your favorite steak.

Now, for ages, the go-to for many of these fractures, especially the ones neatly tucked inside the joint capsule, has been “conservative treatment.” Sounds nice and gentle, right? It usually means avoiding surgery, maybe some fixation to keep things still for a bit, and then hoping nature does its thing. It’s less invasive, less risky in terms of surgical oopsies like nerve damage or scars, and often, the thinking was that the results were pretty decent. But, you know me, I like to peek under the hood and see what’s *really* going on.

So, We Took a Closer Look… A Two-Year Deep Dive!

We embarked on a pretty cool study, if I do say so myself. We followed a group of 26 patients who had a unilateral CHF – meaning the break was only on one side – and were treated conservatively. This wasn’t just a quick check-up; we kept tabs on them for a whole two years. The neat part? It was a self-controlled study. This means we compared the fractured side of their jaw to their own perfectly healthy, unfractured side. Talk about a perfect control group, eh?

What were we looking for? Well, a bit of everything:

- Clinical stuff: How wide could they open their mouth? Was their jaw deviating to one side when they opened? How was their bite lining up?

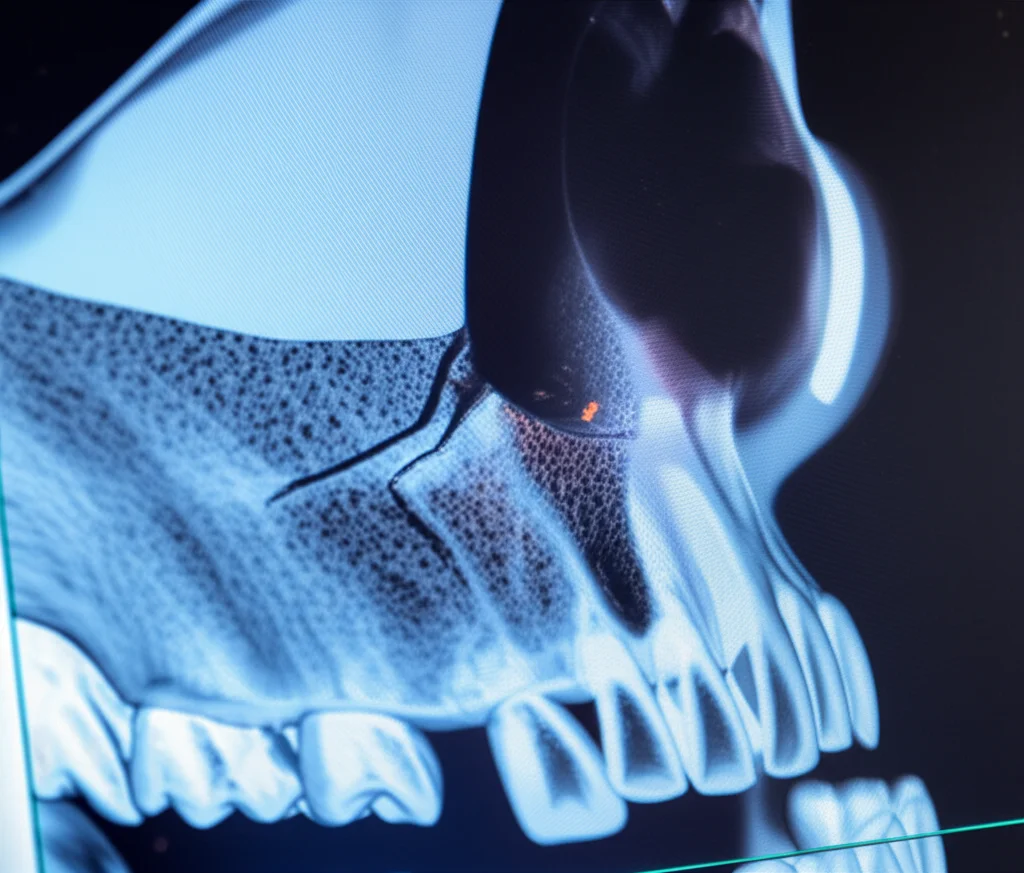

- The nitty-gritty (thanks to CT scans!): We used high-tech imaging to reconstruct and measure the condyle itself, the height of the jaw bone (the ramus), and even the volume of key chewing muscles like the masseter (that big one on the side of your jaw) and the lateral pterygoid (a smaller, deeper muscle crucial for jaw movement).

We took these measurements right after the fracture and then again two years down the line. The goal? To get a clear, quantitative picture of the morphological changes – basically, how the shape and structure of the bone and muscles changed over time with this conservative approach.

What Did We Find? Well, It’s a Bit of a Mixed Bag… Clinically Speaking.

On the surface, there was some good news. The average maximum mouth opening did get better, going from a pretty tight 12.6 mm (imagine trying to eat a burger with that!) to a more functional 27.8 mm. Still, the aim is usually over 35mm for “unrestricted” movement, so it wasn’t a complete home run for everyone.

Mandible deviation – that annoying shift of your chin to one side – did decrease, which is positive. And issues with how teeth met (occlusal relationships) also showed improvement over the two years. So, patients were definitely seeing some benefits. However, we noted that these improvements weren’t always “optimal.” One patient, unfortunately, ended up needing an artificial joint replacement on the fractured side after two years. That tells you something, doesn’t it?

Interestingly, TMJ-MRI scans showed that for most patients, the relationship between the disc in the jaw joint and the condyle remained relatively normal, even with the fracture. The disc is like a little cushion, and if it gets out of place, it can cause a world of trouble. For one patient, though, the disc was displaced right from the start, and two years later, it was still out of whack, and signs of osteoarthritis (that wear-and-tear arthritis) were creeping in. This really underscores how crucial that disc-condyle relationship is.

The Real Eye-Opener: Significant Musculoskeletal Resorption

Now, here’s where things got really interesting, and frankly, a bit concerning. When we looked at those detailed CT reconstructions, we found something pretty stark: significant musculoskeletal resorption on the fractured side. “Resorption” is just a fancy word for loss or shrinkage. And it wasn’t trivial.

Let’s break it down:

- Condylar Volume: The actual bone of the condylar head? It shrank. We saw an average decrease of about 241.86 mm³. That’s a noticeable loss of bone.

- Ramus Height: The vertical height of that part of the jaw bone also took a hit, decreasing by an average of 1.87 mm. This might not sound like much, but in the delicate mechanics of the jaw, it can make a difference to your bite and facial symmetry.

- Masseter Muscle Volume: This was a big one. This powerful chewing muscle lost an average of 3,447.3 mm³ in volume. Think about that – a significant chunk of muscle just… gone.

- Lateral Pterygoid Muscle Volume: This smaller, but vital, muscle also experienced a significant decrease, by an average of 1203.05 mm³.

And the kicker? These changes were statistically significant. Meanwhile, the unfractured side? Pretty much stayed the same. No significant changes there. This really highlighted that the resorption was linked to the fracture and its conservative treatment.

This finding about bone resorption isn’t entirely out of the blue; other studies have hinted that conservative treatment might not be the best for restoring anatomy perfectly. Some have even found that surgical treatment can do a better job at getting the condyle back to its original shape and position. But our study really put some hard numbers on the extent of this resorption, especially for condylar head fractures, and importantly, brought the muscles into the picture.

Why This Matters: A Heads-Up for Surgeons (and Patients!)

So, what’s the big takeaway from all this? Well, it seems that while conservative treatment for condylar head fractures can lead to some functional improvements, it also comes with this under-the-radar consequence of significant bone and muscle loss. The “less optimal improvements” in clinical assessments start to make a lot more sense when you see this underlying resorption.

This is a pretty big deal. It suggests that surgeons really need to be aware of these trends. Conservative treatment might seem like the easier, safer path initially, but if it leads to these kinds of long-term structural changes, we need to weigh the pros and cons very carefully. It’s not just about avoiding surgical scars; it’s about long-term function and health of the entire musculoskeletal apparatus of the jaw.

We even saw that fractures where the fragment was displaced medially (CHF-M type) tended to show more significant decreases in volume and height across the board compared to posterior displacements (CHF-P), though not all those differences reached statistical significance for the P-type. Still, it hints that the type and displacement of the fracture fragment might play a role in how much resorption occurs.

The Often-Overlooked Muscles: A New Piece of the Puzzle

One of the things I’m particularly fascinated by in our findings is the significant resorption of the masticatory muscles – the masseter and the lateral pterygoid. Soft tissue changes around fractures often don’t get the limelight, but they’re clearly super important. Why would these muscles shrink? Well, it could be a “use it or lose it” kind of thing, or perhaps the altered mechanics from the shortened ramus height and changed condyle shape puts different, possibly less, stress on them, leading to atrophy. One theory is that the reduced loading capacity of the fractured condyle just throws the whole masticatory system out of whack.

It’s also possible that some of the initial muscle volume we measured right after the trauma was a bit inflated due to swelling and edema. That’s something to refine in future studies – getting an even more accurate baseline for muscle volume. But even with that consideration, the extent of volume loss at the two-year mark is pretty striking.

The Disc and The Decision

Remember that patient with the displaced disc and developing osteoarthritis? That’s a crucial reminder: the condyle and the articular disc are a team. You can’t just focus on the bone. Before opting for conservative treatment, ensuring that disc is in a good position is paramount to prevent future problems like pain, dysfunction, and arthritis. If the disc is already displaced and can’t be (or isn’t) repositioned, conservative treatment might be setting the patient up for trouble down the road.

So, when it comes to choosing how to treat a condylar head fracture, it’s not a one-size-fits-all situation. We need to consider:

- The exact level and displacement of the fracture.

- The patient’s dental situation and bite.

- Aesthetic and functional goals.

- The patient’s age (remodeling potential can differ).

- And, critically, the state of that articular disc.

For some CHFs, especially with tiny fragments or tricky medial dislocations, open reduction surgery is a real challenge. But our findings suggest we shouldn’t shy away from considering it, or at least having a very frank discussion about the potential long-term morphological changes with conservative treatment.

Final Thoughts: Knowledge is Power

Look, this study had its limitations – a specific number of patients, and the measurements were done by one investigator (though repeated for consistency!). But I genuinely hope it sparks more conversation and research into the soft tissue changes after jaw fractures and gives everyone a clearer insight into what “conservative treatment” for condylar head fractures really entails in the long run.

The main message here? Bone resorption and masticatory muscle atrophy are real things that happen after conservative treatment in many unilateral condylar head fracture cases, especially if there’s medial displacement. Surgeons need to have this on their radar, control the indications for conservative treatment very strictly, and be upfront about these potential less-than-ideal outcomes. It’s all about making the most informed decision for the best possible long-term health of our patients’ jaws!

Source: Springer