Little Hearts, Big News: Kids Dodge Major TAVR Complication!

Hey everyone! I’ve got some really heartening news to share today, especially for families navigating the world of pediatric heart conditions. We’re talking about a procedure called TAVR – that’s transcatheter aortic valve replacement – and how our littlest patients seem to be sailing through one of its potential stormy seas much better than adults. It’s quite fascinating, so let’s dive in!

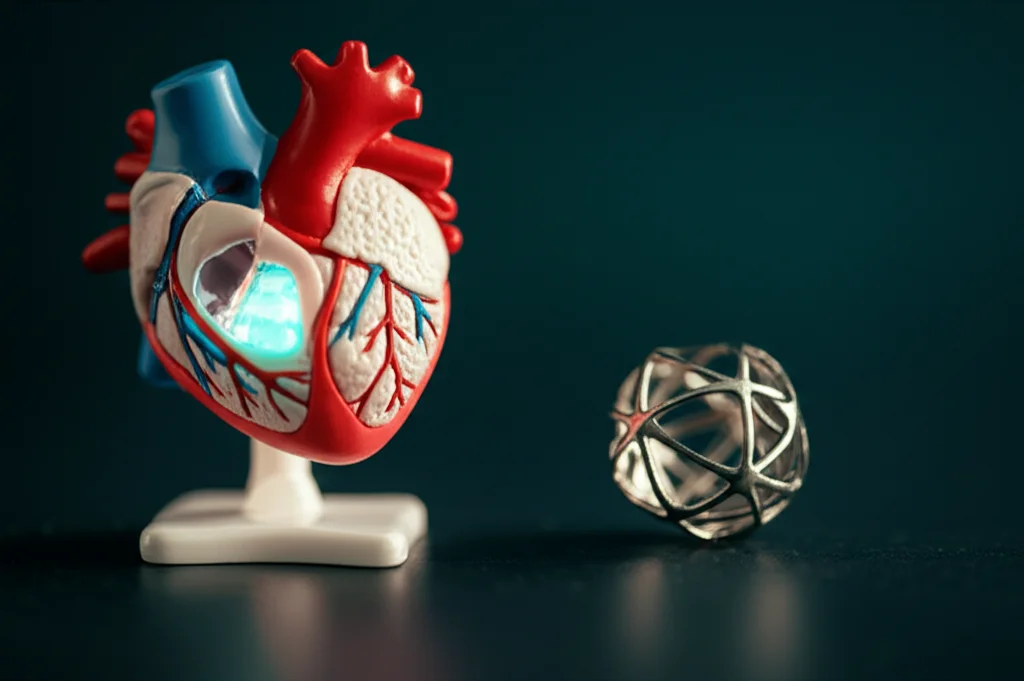

So, What’s TAVR Anyway?

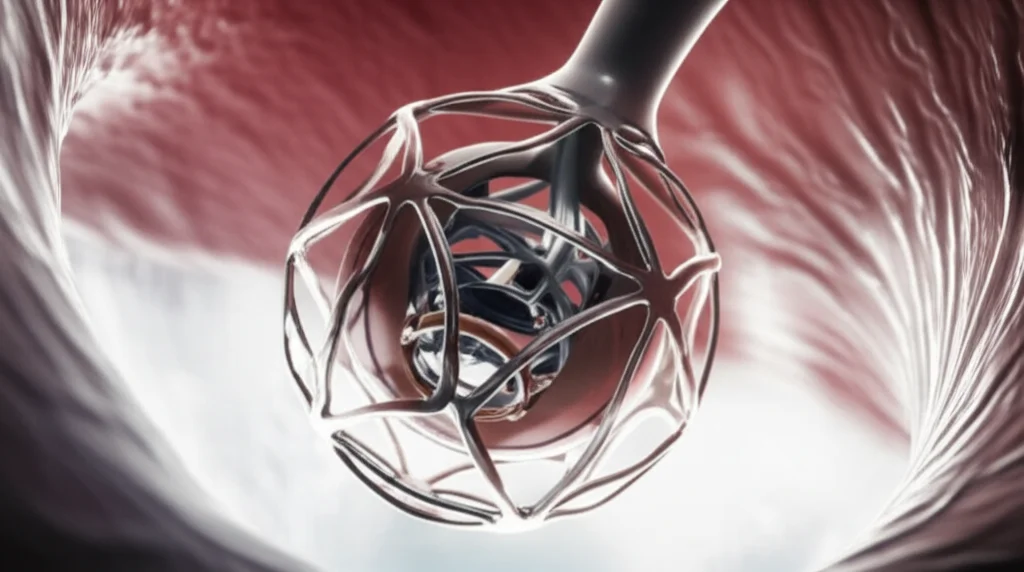

First off, for those not in the know, TAVR is a pretty neat way to replace a faulty aortic valve without resorting to open-heart surgery. Think of it as a less invasive option that’s become a real game-changer, particularly for older adults with calcific aortic stenosis. Since it first made waves around 2010, it’s become the go-to for many, regardless of their surgical risk. Our center has even been a bit of a trailblazer, using TAVR for kids with congenital heart disease (CHD). While there’s a mountain of research on TAVR in adults, we’ve had much less info on how it pans out for children and young adults – until now!

The Adult Story: A Known Hiccup

In the adult world, one of the well-documented bumps in the TAVR road is the risk of conduction abnormalities. This basically means issues with the heart’s electrical system. Sometimes, this can lead to something called complete heart block (CHB), where the heart’s electrical signals don’t get from the upper to the lower chambers properly. When this happens, a permanent pacemaker (PPM) is often needed to keep things ticking along smoothly. For adults, the rates of needing a PPM after TAVR can range anywhere from 4% to 24% in modern times, and historically, it’s even been as high as 51%!

Why does this happen? Well, the heart’s main electrical pathway, the bundle of His, runs quite close to where the new valve is placed. It’s a bit of a delicate dance, and sometimes this pathway can get a bit bruised or bothered during the TAVR procedure. Researchers have identified several risk factors in adults, like having a pre-existing right bundle branch block (RBBB – a type of electrical delay), how deep the new valve is implanted, if the valve is a bit oversized for the patient’s anatomy, and even things like age and how much calcium has built up on the old valve.

The Big Question: What About Our Kids?

This brings us to the crucial question: do these adult risks and rates apply to children and young adults? It’s a super important question because, let’s face it, kids are not just little adults. Their bodies are different, their heart conditions are often different (many have congenital heart disease), and they often have a history of previous heart procedures. In fact, many of these young patients already have some baseline conduction abnormalities before they even get to TAVR. So, could some of those adult risk factors (the ones not tied to old age, anyway) actually be more predictive in kids? And what about other things, like how the heart’s rhythm (ectopy) changes after the procedure? These have been big unknowns.

So, a dedicated team decided to look into this. They wanted to describe what happens with conduction and heart rhythms after TAVR in pediatric and young adult patients with CHD. And honestly, the findings are pretty uplifting!

Digging into the Details: The Study Itself

This was a retrospective look at patients who underwent TAVR at a single center between September 2014 and June 2021. They included 29 patients who received the SAPIEN 3 valve. One patient who already had complete heart block and a pacemaker was excluded, leaving 28 cases for the study. These weren’t tiny babies; the ages ranged from 3.5 to 22 years old, with a median age of nearly 15. About half were male.

The patient group was quite diverse in terms of their heart conditions:

- About 43% had isolated aortic valve disease.

- Roughly 29% had more complex issues with blockages on the left side of the heart.

- Another 29% had other forms of complex congenital heart disease.

Interestingly, a whopping 57% (16 out of 28) already had some kind of conduction abnormality at baseline, with right bundle branch block being the most common. This is a key difference from the general adult TAVR population. Most of these young patients had also been through the wringer before, with many having had previous transcatheter (64%) or surgical (53.6%) aortic valve interventions.

The researchers looked at those known adult risk factors:

- Pre-existing RBBB

- Membranous septum length (a part of the heart near the conduction system)

- Valve implantation depth

- Degree of valve oversizing

They also considered factors unique to this younger, complex group, like having had more than one prior aortic valve intervention or any baseline conduction abnormality.

The Exciting Results: Kids Are Different!

Okay, here’s the headline news: In this group of children and young adults, the need for a permanent pacemaker due to complete heart block after TAVR was rare. Only one patient out of 28 needed a PPM. That’s an incidence of just 3.6%! Compare that to the 4-24% we often see in adults – it’s a big difference, and a very welcome one.

What about other new conduction issues? Well, 9 out of 28 patients (32.1%) did develop some new-onset conduction abnormality right after TAVR, and another two had late-onset issues. The most common were first-degree AV block (a milder form of heart block) and left bundle branch block (LBBB). But here’s more good news: for most of them, these issues resolved during follow-up! By one year post-procedure, all the first and second-degree AV blocks had cleared up, and 60% of the LBBBs had resolved too. Only three patients had persistent conduction abnormalities, including the one who needed the pacemaker and two with LBBB.

And here’s something really intriguing: those risk factors that are so often pointed to in adults? Things like pre-existing RBBB, membranous septum length, how deep the valve was put in, or how much it was oversized? None of these showed a significant association with developing a new conduction abnormality in these young patients. Even having a baseline conduction abnormality or a history of multiple previous valve interventions didn’t seem to predict new problems post-TAVR.

The study also noted that LV function improved in all patients who had dysfunction before, and LV hypertrophy (thickening of the heart muscle) resolved in half of those affected. That’s more good news on the recovery front!

Why Might Kids Fare Better?

This is the million-dollar question, isn’t it? The study authors suggest a few reasons. Firstly, the pediatric cardiac conduction system is just different from that of older adults. It generally has faster conduction, shorter recovery times after an electrical impulse, and importantly, less fibrosis and sclerosis (hardening and scarring) that can come with age and other conditions. In adults, acquired injury to the conduction system from things like ischemia (lack of blood flow) or calcium from the diseased valve invading the conduction pathways is more common.

The valve disease itself might also be different in kids. In adults, we often see a lot of calcification. In pediatric aortic valve stenosis, it might be more about excessive extracellular matrix deposition without all that calcium. This means the TAVR procedure might be interacting with a different kind_of diseased tissue in kids.

It was also noted that younger patients within this pediatric group were even less likely to have new conduction abnormalities. This could be due to an even healthier conduction system or perhaps the left ventricular outflow tract (the part of the heart just below the aortic valve) being more compliant and adaptable in younger children.

The transient nature of most of the conduction abnormalities seen in this study is also really encouraging. It suggests that any “trauma” to the conduction system during TAVR in these young hearts is often something they can bounce back from pretty quickly.

What This Means for Our Little Patients

This research is a big step forward. It’s the first study, as far as we know, to really look at the electrical consequences of TAVR in pediatric and young adult patients, especially those with complex congenital heart disease. For so long, risk prediction for post-TAVR pacemaker needs has been all about adults, whose hearts and underlying issues can be vastly different.

This study gives us a crucial baseline for this specific group. It’s an initial reference point that can help us start building risk models that are actually relevant for kids. When we’re counseling young patients and their families about treatment options for aortic valve disease, having this kind of information is invaluable. These kids are looking at decades of life ahead of them, so understanding long-term effects and safety is paramount.

The findings also touch on whether routine post-discharge heart rhythm monitoring (like with a Holter monitor) is always needed. In this study, none of the remote monitors picked up new abnormal conduction, even though monitors were more often given to kids who had some arrhythmias right after the procedure. The arrhythmias that were seen were generally benign and transient. This hints that routine extensive monitoring might not be necessary for everyone in this younger population, but of course, more research will help fine-tune those recommendations.

A Few Caveats (As Always in Science!)

It’s important to remember the context of this study. It was from a single center and had a relatively small number of patients (less than 30). This makes it tricky to do some of the more complex statistical analyses to definitively nail down risk factors. Being a retrospective study (looking back at records) also has its limitations, as some granular data might not always be captured unless it was a persistent, significant issue.

Measuring things like implantation depth precisely on angiography can also be challenging in kids, where doctors are rightly trying to limit contrast dye exposure. And, of course, this study had limited long-term follow-up. Kids needing TAVR young will likely face more interventions over their lifetime than an elderly patient. We still need more longitudinal studies to fully understand the long-term picture for these brave young hearts.

The Takeaway: A Brighter Outlook!

Despite the limitations, the core message from this research is incredibly positive. Permanent heart block requiring a pacemaker was rare in these children and young adults undergoing TAVR. And, the adult risk factors we’ve worried about don’t seem to be the big players in this younger crowd. Less advanced conduction issues that did pop up mostly resolved, which is fantastic news.

This is a wonderful piece of the puzzle, offering reassurance and paving the way for more tailored care for young TAVR patients. It really underscores that when it comes to heart care, one size definitely does not fit all, and our kids are proving to be remarkably resilient!

Source: Springer