Chicken Champions: Novel Vaccine Fights IBV e NDV with Chimp Power

Hey folks! Let’s talk about something super important for keeping our feathered friends healthy and happy: vaccines! If you’re involved with chickens, you know that two nasty bugs, Infectious Bronchitis Virus (IBV) and Newcastle Disease Virus (NDV), can cause some serious trouble. They hit flocks hard, leading to sickness, lower egg production, and sadly, sometimes even death. This means big headaches and big losses for poultry farmers worldwide.

Keeping chickens healthy is a huge deal for feeding the planet, so finding better ways to protect them from these diseases is crucial. Traditional vaccines have been around for a while, but these viruses are a bit tricky. They mutate and change, meaning the old vaccines don’t always offer full protection against the newer versions popping up. We need something smarter, something that can keep up.

The Problem with the Usual Suspects

IBV is part of the Coronavirus family (yep, like *that* one, but for chickens!). It causes respiratory issues, kidney problems, and drops in egg laying. Its genome is a single strand of RNA, and it’s particularly good at changing its look, especially on its ‘spike’ protein (S protein), which is key for the virus getting into cells. This S protein has different parts (S1 and S2), and the S1 part is the one that really matters for vaccines because it’s where the virus attaches and where the immune system sees it. Because IBV changes so much, there are tons of different strains (genotypes), and a vaccine for one strain might not protect against another. The QX genotype (GI-19) is a big problem, especially in China, causing significant economic damage.

NDV is another major threat, belonging to the Paramyxoviridae family. It’s highly contagious and often fatal, causing respiratory, nervous, and digestive symptoms. Its genome is also single-stranded RNA. Key players here are the Fusion (F) protein and the Hemagglutinin-Neuraminidase (HN) protein. The HN protein helps the virus stick to cells and is great at triggering antibody responses, which is humoral immunity. The F protein helps the virus fuse with the cell and is more involved in getting the cellular immune response going (like T-cells). Like IBV, NDV has different strains and genotypes, and the common vaccine strain (LaSota, genotype II) isn’t always the best match for currently circulating strains like genotypes VII and IX, which are common in Asia. This mismatch can mean less protection and potential vaccine failure.

So, we’ve got two major, evolving threats, and current vaccines sometimes struggle to provide broad, long-lasting protection. It’s a tough spot for the poultry industry.

A Novel Approach: Chimpanzee Adenovirus Vector

This is where the cool science comes in! Researchers are exploring new vaccine platforms, and one promising avenue is using recombinant viral vectors. Think of a viral vector as a safe delivery truck. This study looked at using a *chimpanzee* adenovirus vector (ChAd). Why a chimp one? Well, it’s a non-replicating vector, meaning it doesn’t multiply much in the chicken’s body. This is a good thing because it reduces the chance of the chicken developing a strong immune response *against the vector itself*, which can make booster shots less effective. Plus, chickens don’t seem to have pre-existing antibodies against chimp adenoviruses, which is a problem you can run into with chicken-specific adenovirus vectors. These ChAd vectors are also pretty good at carrying large pieces of genetic material and getting the host cells to express the proteins encoded by those genes.

The idea here was to build a single vaccine that could tackle *both* IBV and NDV. By using a ChAd vector to deliver bits of both viruses – specifically the IBV S1 protein and the NDV HN protein – they hoped to create a bivalent vaccine that could trigger a strong immune response against both pathogens at once. Less jabs needed, broader protection potentially.

Building the Vaccine (PAD-S1-HN)

The scientists got to work. They took the genes for the IBV S1 protein and the NDV HN protein, linked them together, and popped them into the ChAd vector. This new, modified vector was named PAD-S1-HN. They grew this recombinant virus in human cells (HEK293 cells) in the lab.

They did all the necessary checks:

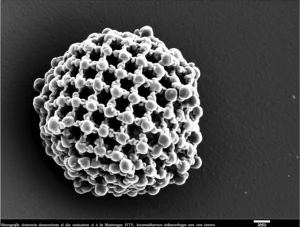

- They looked at it under a transmission electron microscope and confirmed it had the typical adenovirus shape – like a tiny, many-sided ball, about 80-100 nm across. Looked just like the empty vector, which is good.

- They made sure the cells infected with PAD-S1-HN were actually producing the IBV S1 and NDV HN proteins using tests like indirect immunofluorescence (IFA) and western blotting. Yep, the proteins were there!

- They checked if the vaccine was genetically stable over multiple passages (basically, growing it repeatedly in the lab). It stayed stable, with the inserted genes remaining unchanged even after 15 passages. Consistency is key for a vaccine!

- They looked at its growth kinetics – how well and how fast it grew compared to the empty vector. The PAD-S1-HN grew similarly to the empty vector, suggesting adding the viral genes didn’t mess up the vector’s ability to replicate (or rather, express the genes in this non-replicating system).

They even checked if the vaccine could express these proteins in chicken-derived cells (HD11 cells), and it could! All signs pointed to a successfully constructed and stable vaccine candidate.

Putting it to the Test: Animal Trials

Now for the real-world (well, controlled real-world) test! They got 120 healthy, young chickens and split them into four groups:

- Group 1: Got a standard commercial bivalent QX+NDV vaccine.

- Group 2: Got the empty ChAd vector (a negative control).

- Group 3: Got plain PBS (another negative control).

- Group 4: Got the new PAD-S1-HN vaccine.

They gave the vaccines (or controls) via nasal and eye drops when the chickens were 7 days old, and a booster shot at 21 days old.

Throughout the trial, they kept a close eye on the chickens. They checked their weight (they grew normally!), their behavior (they seemed fine!), and collected samples regularly to see what was happening inside. They also checked the environment to make sure the non-replicating adenovirus wasn’t shedding everywhere – it wasn’t detected in feed, water, or feces, which is great for safety.

Immune Response: Getting Ready to Fight

The big question: Did the vaccine make the chickens’ immune systems ready? They measured antibody levels in the blood using ELISA and HI tests.

* Antibodies: By 28 days after the first vaccination, both the PAD-S1-HN group and the commercial vaccine group had developed significant levels of antibodies specifically targeting IBV and NDV. The control groups had none. This showed the new vaccine was definitely triggering the production of these crucial defense proteins.

* Cytokines: They also looked at cytokine levels (like IL-2, IL-4, IL-6, and IFN-γ) in the blood. These are like the signaling molecules of the immune system. The vaccinated groups (both PAD-S1-HN and commercial) showed significantly higher levels of these cytokines compared to the control groups. IL-2 and IFN-γ are linked to cellular immunity (Th1 response), while IL-4 and IL-6 are linked to humoral immunity (Th2 response, antibody production). This indicated the vaccine was stimulating both arms of the immune system. Interestingly, the commercial live vaccine seemed to induce higher IFN-γ levels, possibly because it replicates a bit, mimicking a natural infection more closely. The empty vector didn’t cause a significant cytokine response, which is good for a vector platform.

* Mucosal Immunity: Since IBV and NDV are respiratory/intestinal bugs, defense at these entry points is key. They checked for specific IgA antibodies in fluids from the trachea (windpipe) and intestines. By 28 days, both vaccinated groups had significantly higher levels of IBV- and NDV-specific IgA in these mucosal areas compared to the controls. The commercial vaccine sometimes induced slightly higher mucosal IgA than the new vaccine, but both were much better than nothing. Total mucosal IgA was also higher in vaccinated groups.

In a nutshell, the PAD-S1-HN vaccine did a solid job of waking up the chicken’s immune system, generating antibodies and cellular signals, and boosting defense at the mucosal surfaces.

The Ultimate Test: The Challenge

At 35 days old, the moment of truth arrived. They deliberately exposed the chickens to a mix of live, virulent IBV and NDV viruses. This is the real test of whether the immune response triggered by the vaccine is strong enough to protect them from actual infection.

The results were pretty clear:

* Clinical Symptoms: The chickens in the unvaccinated control groups (PBS and empty vector) got really sick, showing classic signs like sneezing, shaking heads, ruffled feathers, and just looking generally miserable. Morbidity rates were high (over 87%). In stark contrast, the chickens in the PAD-S1-HN group and the commercial vaccine group showed significantly milder symptoms, and far fewer of them got sick (morbidity rates around 25-29%).

* Survival: This is a big one. By day 10 after the challenge, survival rates in the unvaccinated groups were tragically low (12.5% and 16.6%). But in the vaccinated groups, survival was much, much higher – around 75% for the PAD-S1-HN group and 79% for the commercial vaccine group. That’s a massive difference!

* Viral Shedding: How much virus were the chickens spreading? They checked throat and cloacal swabs. Both vaccinated groups had significantly lower viral shedding of both IBV and NDV compared to the unvaccinated groups. For IBV, the PAD-S1-HN group sometimes even showed lower viral loads than the commercial vaccine group in swabs. For NDV, both vaccinated groups were much better than controls, with the commercial vaccine sometimes showing slightly lower loads in swabs than PAD-S1-HN. Less shedding means less spread of the disease, which is a huge win.

Inside Story: Viral Loads in Organs and Tissue Damage

They didn’t stop there. They also looked inside the chickens after the challenge, checking how much virus was in different organs and examining tissue samples under a microscope for damage.

* Viral Loads in Organs: In the unvaccinated chickens, high levels of both IBV and NDV were found in various organs (kidneys, trachea, lungs, spleen, etc.). In the vaccinated chickens (both PAD-S1-HN and commercial), the viral loads in *all* tested organs were significantly lower than in the unvaccinated groups. For IBV, the PAD-S1-HN vaccine was often better than the commercial vaccine at reducing viral loads in organs like the liver, spleen, kidneys, and lungs. For NDV, the commercial vaccine was sometimes better in certain tissues, but PAD-S1-HN was better in others (kidneys, duodenum), and overall, both provided significantly better protection than no vaccine.

* Histopathology: Looking at the tissues confirmed the protection. The unvaccinated chickens showed severe damage in organs like the kidneys, trachea, and spleen. The vaccinated chickens (both groups) showed much milder changes, with significantly less tissue damage compared to the controls. The new vaccine provided protection comparable to the commercial one in preventing these pathological changes.

The Takeaway and What’s Next

So, what’s the big picture? This study successfully developed a novel bivalent vaccine using a chimpanzee adenovirus vector (PAD-S1-HN) that expresses key proteins from both IBV and NDV. It was stable, expressed the right proteins, and most importantly, it worked!

In chickens, it triggered a strong immune response, including antibodies, cytokines, and mucosal immunity. When challenged with live viruses, it provided significant protection, reducing clinical signs, mortality, viral shedding, and tissue damage. Its performance was comparable, and sometimes even better in specific aspects, to a commercially available live attenuated vaccine. This non-replicating ChAd vector approach seems safe and effective, potentially overcoming some limitations of traditional vaccines and other vector types.

However, like any good science, there are always next steps and limitations to consider:

- This study focused on specific strains (IBV QX and NDV F48E9). We need to know if this vaccine can protect against the huge variety of other IBV and NDV genotypes circulating globally. Cross-protection is a big challenge.

- For the NDV component, they only used the HN protein. The F protein is also really important, especially for cellular immunity. Future versions could potentially include both HN and F proteins to maybe get an even broader and stronger immune response.

- How long does the protection last? This study looked at protection up to 10 days post-challenge (which was 35 days old). We need longer-term studies to see if chickens stay protected throughout their lifespan.

- More research is needed on optimizing the vaccine dose, finding the best way to give it to the chickens, and conducting large-scale trials in commercial farm settings to see how it performs in the real world.

Despite these points for future work, this study is a really exciting step forward. Developing this chimpanzee adenovirus-based bivalent vaccine offers a promising new tool in the fight against IBV and NDV, potentially improving poultry health and productivity significantly. It’s a great example of how innovative science can help tackle major challenges in agriculture.

Source: Springer