The Cellular Thermostat: How a Tiny Channel Feels the Heat

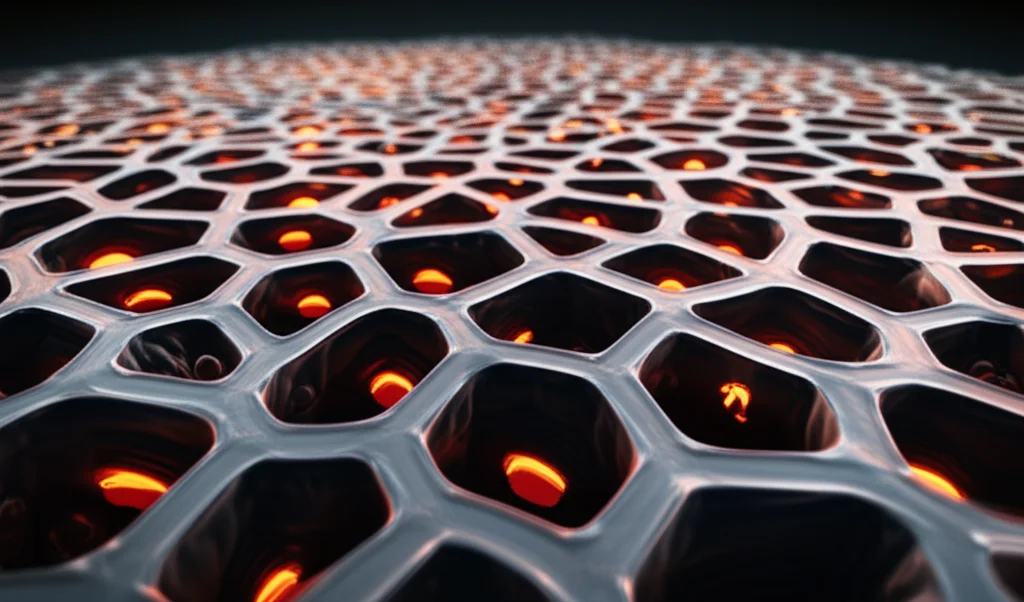

Hey there! Ever wonder how your body just *knows* when it’s hot or cold? I mean, beyond the skin feeling it, how do the cells deep inside, like in your brain or nerves, register temperature changes? It’s pretty wild when you think about it. Turns out, a lot of this sensing magic happens thanks to tiny little gates embedded in cell membranes called ion channels. They’re like the cellular equivalent of a thermostat or a sensor.

We’ve been digging into one particular family of these channels, the K2P channels, specifically the TREK/TRAAK gang. These are special because they let potassium ions through, and uniquely among potassium channels, some of them are known to be sensitive to temperature. Unlike some other famous temperature sensors (the TRP channels, you might have heard of TRPV1 for heat or TRPM8 for cold), these TREK channels actually *dampen* nerve activity when they open, which is a different kind of temperature response.

Finding the Temperature Detectives

So, our mission was to figure out *how* these TREK channels sense temperature. It’s a big question because while we knew they responded, the exact mechanism was a bit of a mystery. We decided to look systematically at different members of the K2P family to see which ones were the real temperature detectives.

What we found was pretty clear: TREK-1 and TREK-2 were strongly activated by heat. Their activity shot up dramatically when the temperature increased. But here’s a surprise – TRAAK, the third member of their own little subfamily, didn’t show this temperature sensitivity at all. This was interesting because they’re quite similar channels, but TRAAK just wasn’t feeling the heat like its cousins.

We checked this a few ways, even using mouse TRAAK and different cell types, just to be sure. Nope, TRAAK remained stubbornly insensitive to temperature changes, even though it worked fine when we poked it with other chemical activators. So, right off the bat, we knew the temperature sensing wasn’t a universal feature of this subfamily; it was specific to TREK-1 and TREK-2.

The Tail Tells the Tale

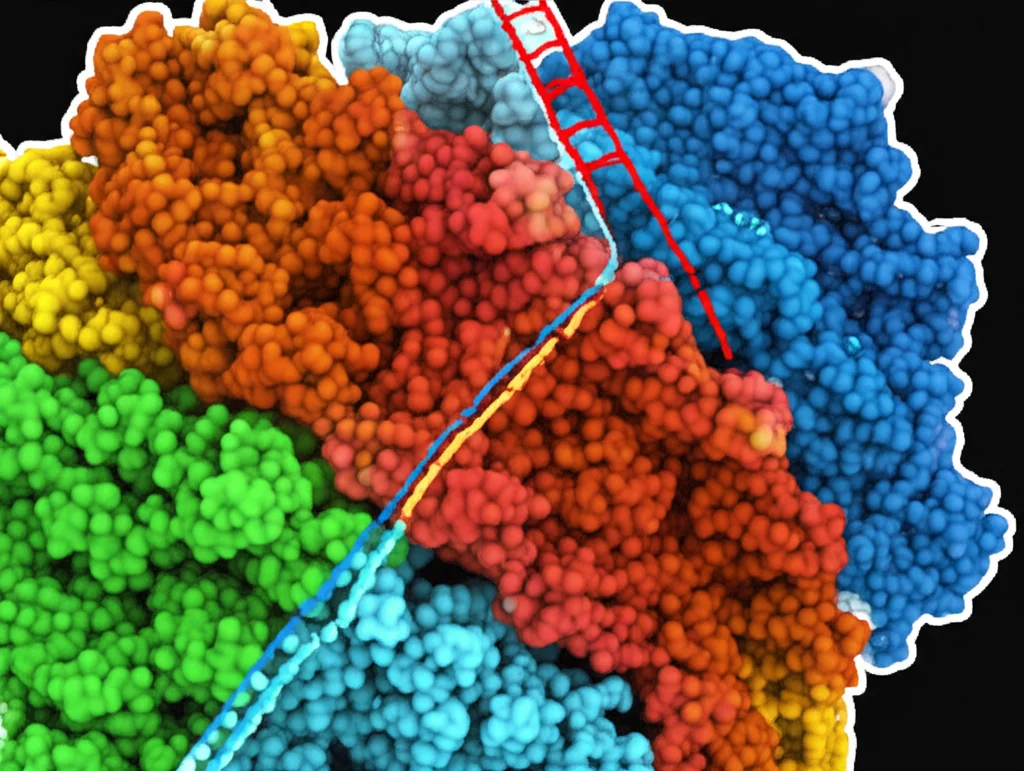

Okay, so TREK-1 and TREK-2 are thermosensitive, and TRAAK isn’t. What’s different about them? We honed in on the channel’s structure, particularly the intracellular C-terminal domain (CTD), which is like the channel’s tail hanging inside the cell. Previous work hinted this tail was important for TREK channels responding to lots of different things, including temperature.

To really test if the tail was the temperature sensor, we did something pretty cool: we swapped the tails! We took the C-terminus from TREK-1 and attached it to the body of TRAAK (creating a “chimeric” channel), and vice versa. And guess what? When TRAAK got the TREK-1 tail, it suddenly became temperature sensitive, just like native TREK-1! When TREK-1 got the TRAAK tail, it lost its temperature sensitivity. This was a big clue! It told us that the C-terminal domain of TREK-1 is not just necessary, but actually *sufficient* to give a channel temperature-sensing abilities, at least within this family.

We also tried swapping the TREK-1 tail onto other types of K2P channels, like TALK-2 or TASK-3, but that didn’t make them thermosensitive. So, while the TREK-1 tail holds the key, it seems it needs the right kind of channel body to work its temperature magic.

Drilling Down to the Hot Spot: The TRE

Since the whole C-terminus is quite long, we wanted to find the *exact* part responsible for sensing temperature. We started chopping off bits of the TREK-1 tail from the end, making shorter and shorter versions of the channel. We tested each truncated version to see if it still responded to temperature.

When we cut off a big chunk, the temperature sensitivity was gone. But when we only removed the very end (about 70 amino acids), the channel still responded pretty well. By carefully trimming, we managed to isolate a specific, relatively small stretch of 18 amino acids within the C-terminus. This little piece, we realized, must be the core Temperature Responsive Element (TRE).

Looking closely at the sequence of this 18-amino acid TRE, we noticed something interesting. It contained known sites for cellular regulation. Specifically, it included a site where an enzyme called PKA (Protein Kinase A) can attach a phosphate group (phosphorylation), and it overlapped with a binding site for a protein called MAP2 (Microtubule Associated Protein 2). This suggested that maybe the temperature sensing wasn’t just about the protein sequence itself, but how it was regulated and what it was connected to inside the cell.

It’s Not Just the Channel, It’s the Connection!

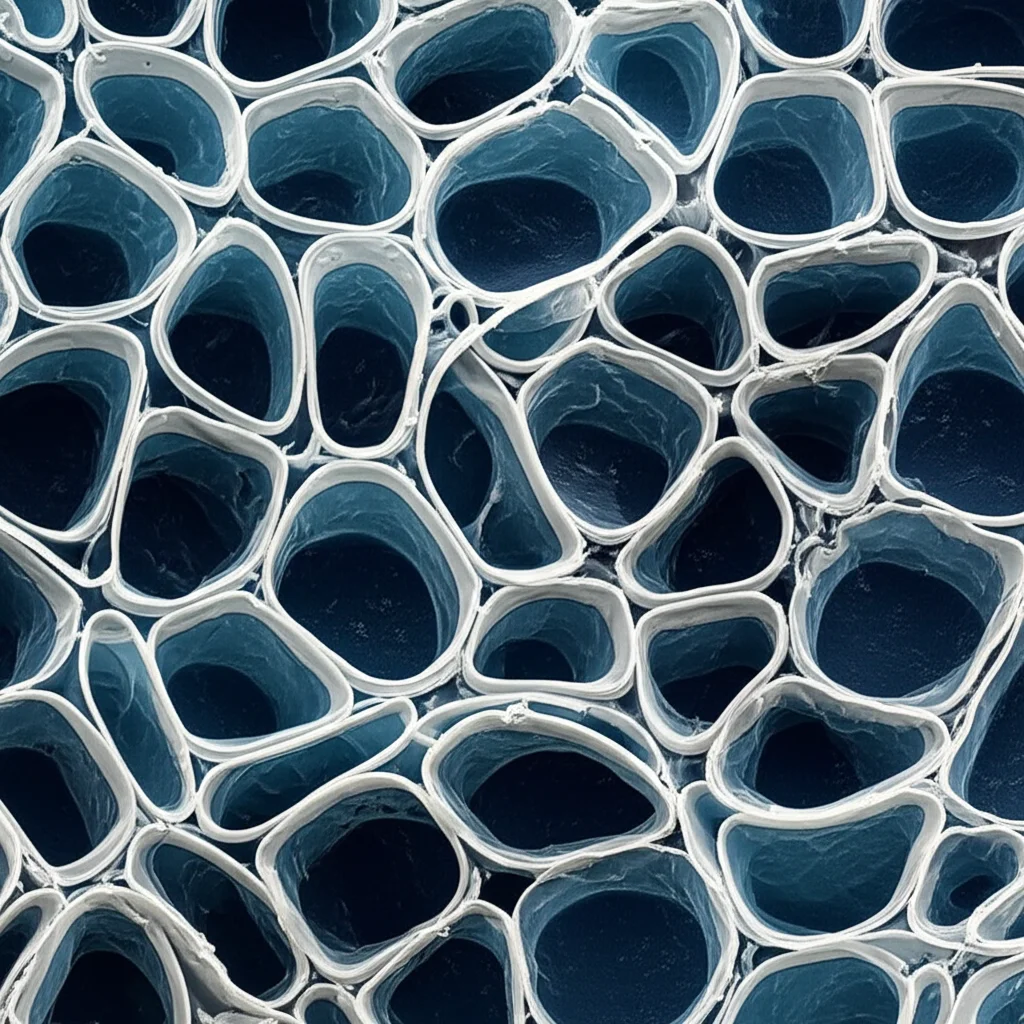

This idea that the channel needs help to sense temperature was reinforced by another set of experiments. We used a technique called patch-clamp, which lets us measure the electrical currents flowing through ion channels in different ways. We could measure the channel while it was still attached to the whole cell (on-cell configuration) or after we’d “excised” a tiny patch of membrane, leaving the channel isolated from the rest of the cell’s interior (inside-out configuration).

What we saw was striking: TREK-1 channels were beautifully temperature sensitive when measured on the whole cell or in the on-cell mode. But as soon as we pulled the patch away from the cell (inside-out), they completely lost their temperature sensitivity! They were still functional – we could activate them with chemicals – but the temperature response vanished. This strongly suggested that some factor or structure *inside* the cell, something that gets lost when you excise the patch, is absolutely essential for TREK channels to sense temperature.

Think of it like a fancy sensor that needs to be plugged into a specific system to work. The TREK channel is the sensor, but it needs to be “plugged in” to the cellular machinery to feel the heat (or cold!).

Hooked Up to the Scaffolding: The Microtubule Link

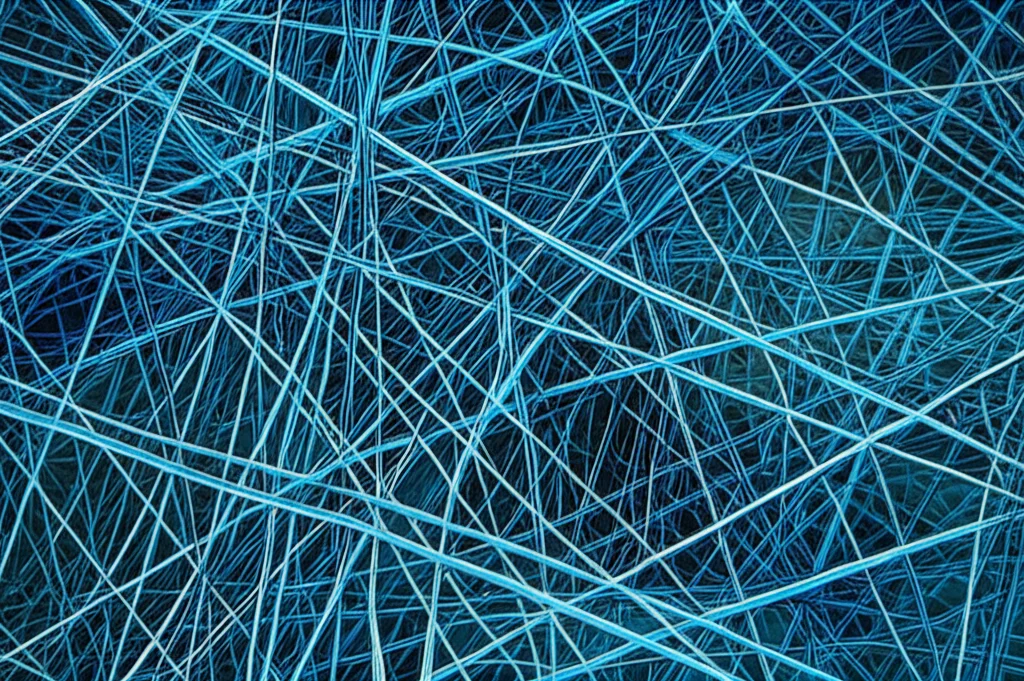

Given that the TRE overlaps with a binding site for MAP2, a protein known to interact with the cell’s internal scaffolding, the cytoskeleton, we wondered if this scaffolding was the missing piece. The cytoskeleton is like the cell’s internal road network and structural support, made of different components like actin filaments and microtubules.

We used drugs to disrupt these different parts of the cytoskeleton. When we messed with the actin network, it didn’t have much effect on the TREK channel’s temperature sensing. But when we disrupted the microtubule network, bam! The temperature sensitivity was significantly suppressed. We also mutated the MAP2 binding site on the TREK-1 channel itself, making it harder for MAP2 to connect. This mutation also drastically reduced the channel’s ability to sense temperature.

This was a major breakthrough! It seems the TRE in the TREK-1 tail needs to be physically connected to the microtubule network, likely via MAP2, for the channel to function as a temperature sensor. The channel’s temperature sensitivity isn’t an intrinsic property of the protein alone, but rather depends on its interaction with the cell’s internal structure. Temperature changes might somehow alter this connection or the dynamics of the microtubule network itself, which then signals the channel to open or close.

The PKA Switch: On or Off for Temperature Sensing

Remember that PKA phosphorylation site we found in the TRE? That turned out to be another critical piece of the puzzle, but in a different way. We tested what happens when PKA is active. We used chemicals that activate PKA, and what we saw was incredible: activating PKA completely *abolished* the temperature sensitivity of TREK-1 channels. They just stopped responding to heat!

This wasn’t because the channels were broken; they could still be activated by other means. It was specifically the *temperature* response that was switched off. We also used a drug to inhibit PKA, and that actually seemed to enhance the temperature response, or at least prevent it from being switched off. To confirm this, we mutated the PKA phosphorylation site itself – mimicking the phosphorylated state (S348D mutation) also killed the temperature sensitivity, while mimicking the unphosphorylated state (S348A mutation) had no effect on it. We even activated PKA through a more natural cellular pathway (using a dopamine receptor), and that also switched off the temperature sensing.

So, PKA doesn’t *sense* temperature itself, but it acts like a molecular switch. When PKA phosphorylates the TREK-1 channel (at S348), it turns off its ability to sense temperature. When PKA is inactive, or the site isn’t phosphorylated, the switch is ‘on’, and the channel *can* sense temperature. This gives the cell a powerful way to fine-tune its temperature response based on its current internal state and signaling activity.

Putting It All Together: A Connected Sensor

So, here’s the picture that emerges: TREK-1 and TREK-2 channels sense temperature not because they are intrinsically built that way, but because a specific 18-amino acid region (the TRE) in their C-terminal tail connects to the cell’s microtubule network, likely via proteins like MAP2. This connection is the actual temperature-sensing unit. Temperature changes might affect the dynamics of the microtubules or the link itself, which then causes the channel to open or close.

But the cell has a master control: PKA. When PKA is active, it phosphorylates the TREK-1 channel at a specific site within the TRE. This phosphorylation acts like a switch, somehow disrupting or altering the connection to the microtubule network, effectively turning off the channel’s temperature sensitivity. When PKA is inactive, the connection is maintained, and the channel is free to sense temperature.

It’s a beautiful system of regulation! The channel itself is a gate, the C-terminus is the lever, the microtubule network is the actual sensor (or part of it), and PKA is the switch that decides if the lever is connected to the sensor at all.

Why Does This Matter?

This isn’t just cool cellular trivia. TREK channels are found in important places for temperature sensing. They’re in the nerves that feel temperature in your skin and organs (DRG/TG neurons) and also in the part of your brain that controls body temperature (the preoptic area or POA in the hypothalamus).

In those peripheral nerves, TREK-1 often works alongside TRPV1, the heat-sensing channel. TRPV1 *opens* with heat, exciting the neuron. TREK-1 *opens* with heat too, but since it’s a potassium channel, it makes the neuron *less* excitable, dampening the response. They’re like opposing forces balancing the temperature signal.

Interestingly, TRPV1 can be made *more* sensitive to heat by PKA phosphorylation, especially during inflammation, contributing to that painful heat hypersensitivity you feel when you have a sunburn or infection. Now we see that TREK-1 is made *less* sensitive to heat by PKA phosphorylation. It’s like PKA is coordinating the response of these two channels! In inflammation, PKA ramps up TRPV1 sensitivity while shutting down TREK-1 sensitivity, shifting the balance towards increased pain signaling from heat.

In the brain’s thermostat area (POA), TREK channels also play a role in setting your body’s temperature set point. During things like fever, signaling pathways involving prostaglandins can affect PKA activity. If PKA activity is suppressed (as happens with some fever signals), our findings suggest TREK channels would become *more* temperature sensitive. This increased sensitivity could contribute to changing the firing rate of those warm-sensitive neurons in the POA, helping to raise the body’s temperature set point during a fever.

A New Way to Think About Sensing

What we’ve uncovered here is a fascinating example of how ion channels can sense the environment. It’s not always just about the protein’s structure changing directly with temperature. Sometimes, the channel needs to be part of a larger cellular complex, connected to the cell’s internal scaffolding, to gain its sensing abilities. And the cell can then use signaling pathways, like the PKA system, to act as a switch, controlling whether or not that sensor is active. It adds a whole new layer of complexity and control to how our cells perceive the world, or in this case, the heat!

Source: Springer