Unmasking AML’s Shield: What CD47 Tells Us About Prognosis

Hello there! Let’s talk about something pretty important in the world of blood cancers, specifically Acute Myeloid Leukemia (AML).

AML is a tough one, a cancer of the blood and bone marrow that happens when the factory making your blood cells goes a bit haywire. It’s the most common acute leukemia in adults, and sadly, the outcomes aren’t always great, especially for older folks. So, researchers like us are constantly looking for new ways to understand this disease better, predict how it might behave, and find new targets for treatment.

One fascinating player in this whole drama is a protein called CD47. Think of CD47 as a kind of secret handshake or a “don’t eat me” signal that pretty much all healthy cells use. It binds to another protein called SIRPα on immune cells, particularly macrophages (the body’s clean-up crew), essentially telling them, “Hey, I’m one of the good guys, move along!” This is super important for keeping our own tissues safe from being mistakenly attacked by our immune system.

The Cancer Connection: CD47 as a Tumor’s Disguise

Now, here’s where it gets tricky. Cancer cells, being the sneaky things they are, often hijack these normal biological processes to their advantage. Many types of cancer, including AML, have been found to overexpress CD47. Why? To put on that “don’t eat me” disguise and evade detection and destruction by those very same macrophages. It’s a bit like a wolf putting on sheep’s clothing to blend in with the flock. This mechanism is actually quite similar to the more widely known PD1-PD-L1 pathway, where cancer cells use PD-L1 to shut down T cells.

Naturally, if cancer cells are using CD47 to hide, you’d think that having *more* of this protein on AML cells might be bad news. And indeed, some studies have suggested that high CD47 expression in AML patients is linked to a poorer prognosis and a higher chance of the disease coming back. But here’s the catch: not all studies agree, and there hasn’t been a standard way to measure CD47 expression on AML blasts (those abnormal, rapidly dividing cells) in routine clinical practice. This makes it hard to really nail down its true value as a prognostic marker.

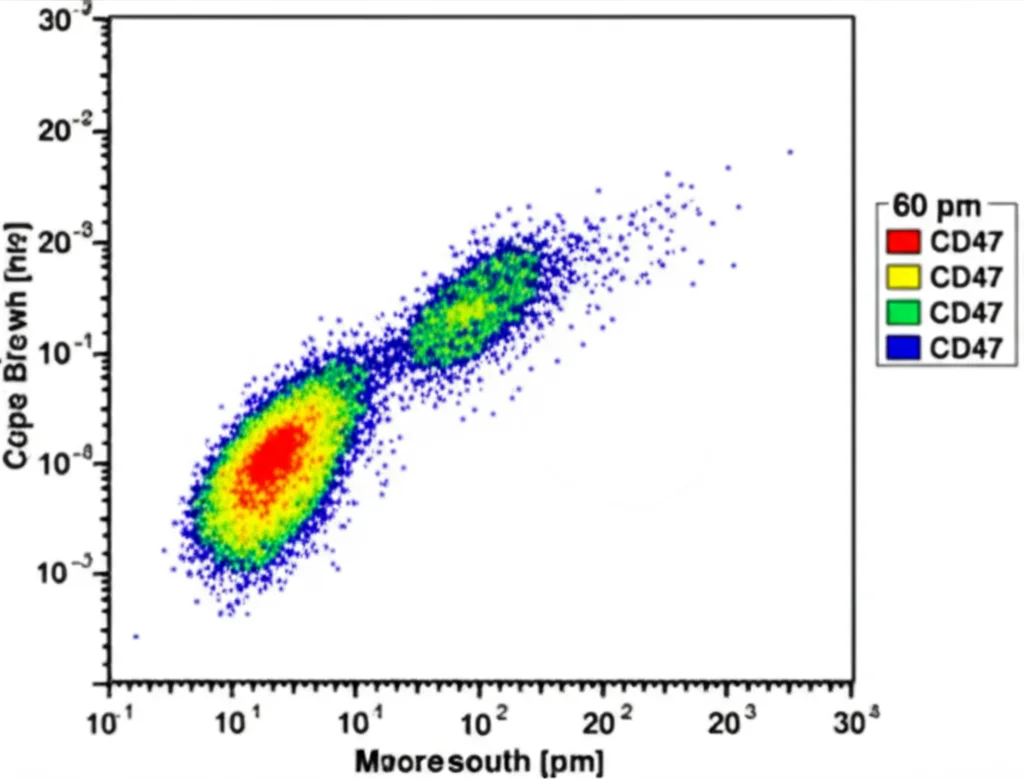

Our Dive into CD47 with Flow Cytometry

So, we decided to take a closer look. Our goal was to investigate the relationship between CD47 expression on AML blasts from bone marrow samples and how patients fared. We used a technique called flow cytometry, which is great for looking at proteins on the surface of cells and can give us a quantitative measure of how much is there. We measured CD47 expression in terms of Median Fluorescence Intensity (MFI) – basically, how brightly a fluorescent tag attached to the CD47 protein glows, giving us a proxy for how much CD47 is present on each cell.

We included patients diagnosed with AML at our center between late 2021 and mid-2024, excluding a specific type called Acute Promyelocytic Leukemia (APL). We collected bone marrow samples at diagnosis and ran them through the flow cytometer. We also gathered a bunch of clinical data on these patients – things like their age, how many blasts were in their blood and bone marrow, their white blood cell count, and other markers of disease burden.

What We Found: CD47 and the Bad News Bearers

First off, we found CD47 expressed on AML blasts in every single patient we looked at. That wasn’t too surprising, given its ubiquitous nature. The median level (MFI) was 16.8, but there was a huge range, from very low to very high.

Here’s where it got interesting: when we looked at CD47 expression as a continuous variable (meaning we considered the actual level, not just high vs. low based on a cutoff), we saw some significant correlations. Higher CD47 levels on AML blasts were associated with:

- Higher White Blood Cell (WBC) count

- Higher percentage of blasts in the bone marrow

- Higher percentage of blasts in the peripheral blood

- Higher LDH levels

These are all generally considered indicators of a higher disease burden, so finding CD47 linked to them makes sense – the more aggressive the disease seems, the more it might be relying on that “don’t eat me” signal.

Now for the big question: prognosis. When we crunched the numbers, we found that higher expression of CD47 was indeed associated with reduced overall survival in our group of patients. The hazard ratio was 1.04, which might sound small, but it was statistically significant (p=0.047). This suggests that for every little increase in CD47 expression, the risk of death increased slightly.

Interestingly, CD47 expression didn’t seem to correlate with progression-free survival (PFS) in our study, nor did it align with the standard genetic risk classification for AML. We also looked at PD-L1 expression, another immune checkpoint, but found no statistical link between CD47 and PD-L1 levels on the AML cells.

Nuances and the Bigger Picture

One thing we considered was comparing CD47 expression on AML blasts to normal cells. We initially compared it to residual normal lymphocytes in the bone marrow, which are known to express CD47. Only a small percentage of patients (14.3%) had higher CD47 on their AML blasts than on these lymphocytes, and this difference didn’t seem to predict prognosis. This made us think that maybe lymphocytes aren’t the best control population, and treating CD47 as a continuous variable (the MFI value itself) was a more informative approach, which is what led us to the survival correlation.

Despite the association with reduced overall survival, we couldn’t find a clear cutoff value for CD47 expression that could reliably predict death, relapse, or response to treatment. This might be partly due to the relatively small size of our study group (35 patients).

It’s also crucial to remember that CD47 doesn’t exist in a vacuum. It’s part of a complex tumor microenvironment – the whole ecosystem of cells, blood vessels, and signals surrounding the cancer. Macrophages, for instance, can be polarized into different types (M1 vs. M2), and AML cells are known to push them towards the M2 type, which actually helps the tumor grow and resist treatment. The CD47-SIRPα interaction is just one piece of this intricate puzzle, interacting with many other factors that influence how the immune system sees (or doesn’t see) the cancer.

Looking Ahead: Targeting CD47

Because CD47 plays this role in immune evasion, blocking the CD47-SIRPα pathway is a hot area for developing new therapies. The idea is to remove that “don’t eat me” signal and let the macrophages do their job. Several agents targeting this pathway are in development.

However, it’s not been a straight path. Magrolimab, one of the first anti-CD47 antibodies, showed some initial promise when combined with other drugs in AML, but recent phase 3 trials were stopped due to lack of efficacy and increased mortality. This highlights the complexity – simply blocking CD47 might not be enough. Macrophages also need a “eat me” signal (like those triggered by certain antibodies binding to cancer cells) to really get going. Future therapies might need to be smarter, perhaps activating these “eat me” signals alongside blocking the “don’t eat me” one, or combining CD47 blockade with other immunotherapies.

So, What’s the Takeaway?

In our study, despite the limited number of patients, we found that measuring CD47 expression on AML blasts using flow cytometry showed a statistically significant association with reduced overall survival. It also correlated with markers of higher disease burden. This adds evidence that CD47 overexpression is indeed linked to a worse outcome in AML, at least in this specific patient group, and that flow cytometry is a viable way to measure it.

But honestly, this is just one piece of the puzzle. We need larger studies to really confirm these findings, figure out if there’s a specific level of CD47 that clearly defines a “high-risk” group, and understand how CD47 fits into the whole complex tumor microenvironment. Ultimately, the hope is that by better understanding CD47’s role, we can identify which patients might benefit most from those emerging CD47-SIRPα blocking therapies, moving us closer to more personalized and effective treatments for AML.

It’s a challenging field, but every study like this brings us a little closer to cracking the code of AML.

Source: Springer