Uncovering the Immune Shield: CD105 Fibroblasts and Breast Cancer Risk

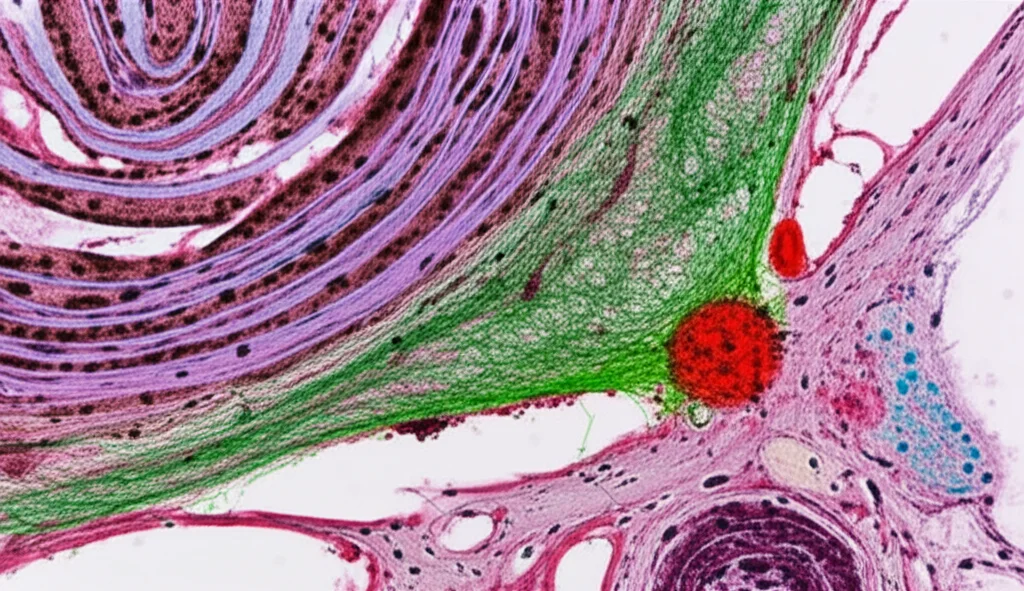

Hey there! Let’s dive into something super important and, frankly, pretty fascinating about breast cancer risk. We all know that getting older is a big factor when it comes to breast cancer, right? But it’s not just about the epithelial cells – the ones that actually *become* the cancer. Nope, the tissue surrounding them, the ‘stroma,’ plays a huge role too. Think of it as the environment where the seeds of cancer might decide to sprout. And in this environment, there are key players: fibroblasts and macrophages.

The Breast’s Inner World: TDLUs and Their Neighbors

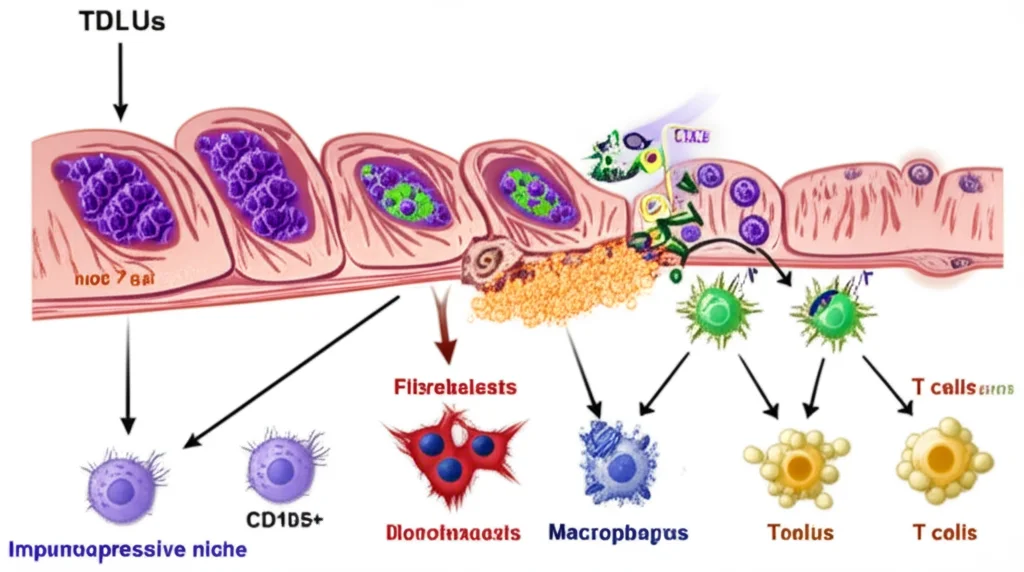

So, what are we talking about when we say ‘stroma’? We’re looking at the tissue around the terminal ductal lobular units (TDLUs). These are the tiny structures in your breast responsible for making milk. They’re incredibly dynamic throughout a woman’s life, constantly changing. And guess what? Most breast cancers start right here, in these dynamic TDLUs. If we can figure out *how* this dynamic microenvironment contributes to increased risk, well, that’s a game-changer for understanding who’s most susceptible and maybe even finding ways to prevent it.

Fibroblasts and macrophages are like the essential neighbors in this TDLU environment. They’re crucial for the normal development and health of the breast. We know they interact a lot in established tumors, but their interactions in *normal* tissue and how they might set the stage for cancer? That’s been a bit of a mystery.

Spotlight on CD105+ Fibroblasts

Turns out, not all fibroblasts are the same. Scientists use markers to identify different subtypes. Two markers, CD105 and CD26, help distinguish these fibroblast populations. In humans, CD105 seems to be a more reliable marker, especially for fibroblasts found right around those TDLUs. While we know cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) have immune-regulating jobs, we haven’t really understood how normal fibroblasts do this, or how they change with age or other risk factors.

Macrophages, the immune cells in this neighborhood, are also super adaptable. They can be ‘pro-inflammatory’ (think fighting off invaders) or ‘anti-inflammatory’ (think tissue repair and calming things down). With age, the macrophages around TDLUs tend to become more anti-inflammatory. This got us thinking: Is there a connection between these changing macrophages and specific fibroblast types as we age or have other risk factors, and could this link to cancer susceptibility?

What We Did: A Deep Dive into Fibroblasts

To figure this out, we got samples from women undergoing breast surgeries – some at average risk, some younger, some older, and some with BRCA1 gene mutations (which significantly increase breast cancer risk). We grew their peri-epithelial fibroblasts (the ones near the TDLUs) in the lab. We then sorted them based on whether they expressed CD105 (CD105+) or not (CD105−). We looked at how they grew, what genes they expressed, what proteins they secreted, and how they behaved, especially their ability to differentiate into other cell types.

Crucially, we set up co-cultures – putting these fibroblasts together with macrophages and T cells – to see how the CD105+ fibroblasts influenced the immune cells. We wanted to see if they were creating an environment that might dampen the immune system’s ability to spot trouble, like early cancer cells.

The Big Reveal: CD105+ Fibroblasts are Key Players

So, what did we find? It was pretty eye-opening! We saw that CD105+ fibroblasts are indeed more common in older women and in women with BRCA1 mutations. This immediately suggested they might be linked to increased risk. Interestingly, these CD105+ fibroblasts grew slower in the lab compared to their CD105− counterparts.

Looking at their genes (RNA-sequencing), the CD105+ fibroblasts had a distinct signature. They were enriched for pathways related to things like myogenesis (muscle-like differentiation), angiogenesis (blood vessel formation), adipogenesis (fat cell formation), and TGFβ signaling. But here’s the kicker: they were also strongly enriched for pathways related to inflammation and, significantly, negative regulation of the immune system. This really started to paint a picture of these cells potentially creating an immunosuppressive environment.

We also saw that CD105+ fibroblasts from BRCA1 mutation carriers had their own unique transcriptional profile, enriched for pathways linked to fibrosis and chronic inflammatory disorders. This further strengthened the idea that these specific fibroblasts are deeply involved in immune interactions, perhaps even more so in high-risk individuals.

Turning into Fat and Secreting Signals

Remember adipogenesis? We tested if these fibroblasts could turn into fat cells, and yes, the CD105+ fibroblasts showed a robust ability to differentiate into adipocytes (fat cells) in culture. While not statistically significant across all groups, the strains with the highest adipogenic potential were from older women, hinting that these fibroblasts might contribute to the increase in breast fat tissue seen with age.

Then we looked at the proteins they secrete using a Luminex assay. Out of 19 proteins we could reliably measure, six were significantly more abundant in the soup from CD105+ fibroblasts. And guess what these proteins are involved in? You got it – establishing an immunosuppressive microenvironment and directly influencing macrophages towards an anti-inflammatory state. Proteins like CCL2, IL-8, and M-CSF were among those increased, all known players in recruiting and polarizing macrophages.

It’s like these CD105+ fibroblasts are sending out chemical signals that tell the immune system to stand down. We also saw some interesting tensions in the secreted proteins – some promoting myofibroblast traits or angiogenesis, others inhibiting them. It’s a complex signaling network!

The Immune Cell Conversation: Fibroblasts and Macrophages

This is where the co-culture experiments came in. We polarized macrophages in the lab to be either pro-inflammatory or anti-inflammatory, then put them together with sorted CD105+ or CD105− fibroblasts. After a few days, we checked the macrophages’ markers and gene expression.

What we observed was that fibroblasts, in general, helped macrophages maintain or even enhance their polarization state compared to just being in media alone. But the CD105+ fibroblasts had specific effects:

- They significantly reduced the expression of the pro-inflammatory marker TNFα in pro-inflammatory macrophages.

- They increased the expression of anti-inflammatory markers like CD163 and IL33 in anti-inflammatory macrophages.

- They generally nudged macrophages towards a more anti-inflammatory, potentially immunosuppressive, profile.

It seems these CD105+ fibroblasts are quite persuasive in their conversations with macrophages!

Adding T Cells to the Mix

Macrophages influence T cells, which are critical for adaptive immunity – the immune system’s specific, targeted response, including killing cancer cells. Anti-inflammatory macrophages are known to suppress T cell proliferation. We set up tricultures with stimulated T cells, polarized macrophages, and either CD105+ or CD105− fibroblasts.

As expected, anti-inflammatory macrophages significantly suppressed T cell proliferation. Now, here’s the crucial part: CD105+ fibroblasts *maintained* this suppressive effect of anti-inflammatory macrophages on CD4+ T cells (a type of helper T cell). But the CD105− fibroblasts? They actually *reduced* the ability of anti-inflammatory macrophages to suppress CD4+ T cell proliferation! This suggests that CD105+ fibroblasts help keep the brakes on a key part of the immune response.

Bringing It Back to Real Tissue

Lab experiments are great, but how does this translate to actual breast tissue in women? We looked at publicly available single-cell RNA-sequencing data from human breast tissue. We created a “CD105 signature” based on the genes highly expressed in our cultured CD105+ fibroblasts and looked for this signature in the tissue data.

The CD105 signature was indeed enriched in a fibroblast subtype found around TDLUs in this tissue data. Importantly, this signature was more enriched in fibroblasts from postmenopausal women and women with dense breasts – both groups known to have increased breast cancer risk. We also saw that in postmenopausal women, there were more interactions inferred between anti-inflammatory (M2) macrophages and these CD105-signature-enriched fibroblasts compared to premenopausal women.

Using a proxy marker, CD248 (which is often expressed with CD105), we also saw higher expression in the lobules (where TDLUs are) compared to ducts in tissue sections. While we didn’t see a clear difference in CD248 expression in tissue from BRCA1 carriers versus average risk women (which was a bit surprising given our culture results), it highlights the challenges of translating findings perfectly between culture and complex tissue.

Overall, the tissue data supports the idea that the CD105+ fibroblast population is relevant in vivo, increases with age, localizes to the high-risk TDLU area, and talks more with anti-inflammatory macrophages in older women. This fits perfectly with our lab findings about them creating an immunosuppressive niche.

Why This Matters for High-Risk Women

Think about it: older women and women with BRCA1 mutations are already at higher risk. Our work suggests that in these women, the very environment within their breast tissue might be less equipped to fight off early signs of cancer. The increased presence and activity of CD105+ fibroblasts, nudging macrophages towards an anti-inflammatory, immune-suppressing state, could be a crucial piece of this puzzle. It’s like they’re building a little ‘immune shield’ around potential trouble spots, allowing rogue cells to potentially escape detection.

This concept aligns with other findings in BRCA1 carriers, like increased immune cell infiltration but also signs of immune exhaustion. It’s not just about *having* immune cells there, but whether they are *functional* and able to do their job.

Looking Ahead: Targeting the Niche?

Understanding these specific fibroblast populations is super important. It helps us understand the normal breast, the precancerous state, and even where cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) come from. CD105+ CAFs are linked to worse outcomes in established breast cancer, so understanding their origins and functions in the *pre-cancer* setting is vital.

Could we potentially target these CD105+ fibroblasts or the signals they send out? There are already therapies targeting CD105 being explored for other cancers. Could a similar approach, perhaps short-term or preventative, be used in high-risk women to reshape the stromal environment and make it less hospitable for cancer initiation? It’s a far-fetched idea right now, but this research opens up those possibilities.

Of course, there are challenges. Fibroblast populations are complex and dynamic. Studying them in culture has limitations compared to the real tissue environment. Detecting markers like CD105 in tissue can be tricky. And the interactions between all the different cell types are incredibly intricate. We need more studies, more samples, and more sophisticated ways to look at these cells directly in tissue.

But for now, what we’ve found is pretty clear: CD105+ fibroblasts are enriched in women at high risk, they have characteristics suggesting they contribute to an aged, more adipogenic stroma, and they play a significant role in creating an immunosuppressive environment by influencing macrophages and, consequently, T cells. This work gives us a much clearer picture of how the stromal neighborhood might be contributing to breast cancer susceptibility.

Source: Springer