Unlocking the Heart’s Hidden Stress: Validating a Key Tool in Iran

Hey there! Let’s talk about something super important but often overlooked when it comes to heart health: the emotional stuff. We all know heart disease is a big deal globally, causing millions of heartaches (literally and figuratively). But beyond the physical symptoms, there’s a whole world of psychological challenges that patients face. Think anxiety, stress, and this tricky thing called “cardiac distress.”

What Exactly is Cardiac Distress?

It’s more than just feeling a bit down or worried. Cardiac distress is this complex mix of emotional, cognitive, and even physical symptoms that pop up after a heart event or surgery. It messes with your head, your feelings, and your ability to just live your daily life and manage your condition. Imagine constantly worrying about the future, feeling disconnected, or struggling with changes to your routine and identity. It can make managing your heart condition way harder, leading to more hospital visits and generally not-so-great outcomes.

The Need for the Right Tools

Now, we’ve got tools to measure anxiety and depression, sure. But cardiac distress is its own beast, covering a wider range of feelings and challenges specifically tied to having heart disease. And here’s the kicker: how people experience and cope with this distress can be super different depending on their culture. So, a tool that works great in one place might not quite hit the mark in another. That’s where the Cardiac Distress Inventory (CDI) comes in. It was developed to specifically measure this kind of heart-related psychological distress. But before we can use it everywhere, we need to make sure it works reliably and accurately in different cultural settings.

Our Mission: Validating the CDI in Iran

That’s why we embarked on this study. We wanted to see if the Farsi version of the CDI, specifically the shorter 10-item version we ended up with, was a valid and reliable tool for assessing cardiac distress in Iranian patients with heart disease. It’s crucial because having a culturally adapted tool means healthcare providers in Iran can get a real handle on what their patients are going through emotionally, beyond just the medical charts. This helps them offer better, more personalized support.

How We Went About It

We gathered data from 400 adult patients with heart disease in Iran between October and December 2024. We used convenience sampling from cardiac clinics – basically, whoever was available and willing to participate, met our criteria, and gave their okay. The first step was translating the CDI into Farsi, following the World Health Organization’s guidelines to make sure we got it right. We had translators work independently, then experts reviewed and refined the Farsi version, and finally, it was translated back to English to check for accuracy against the original.

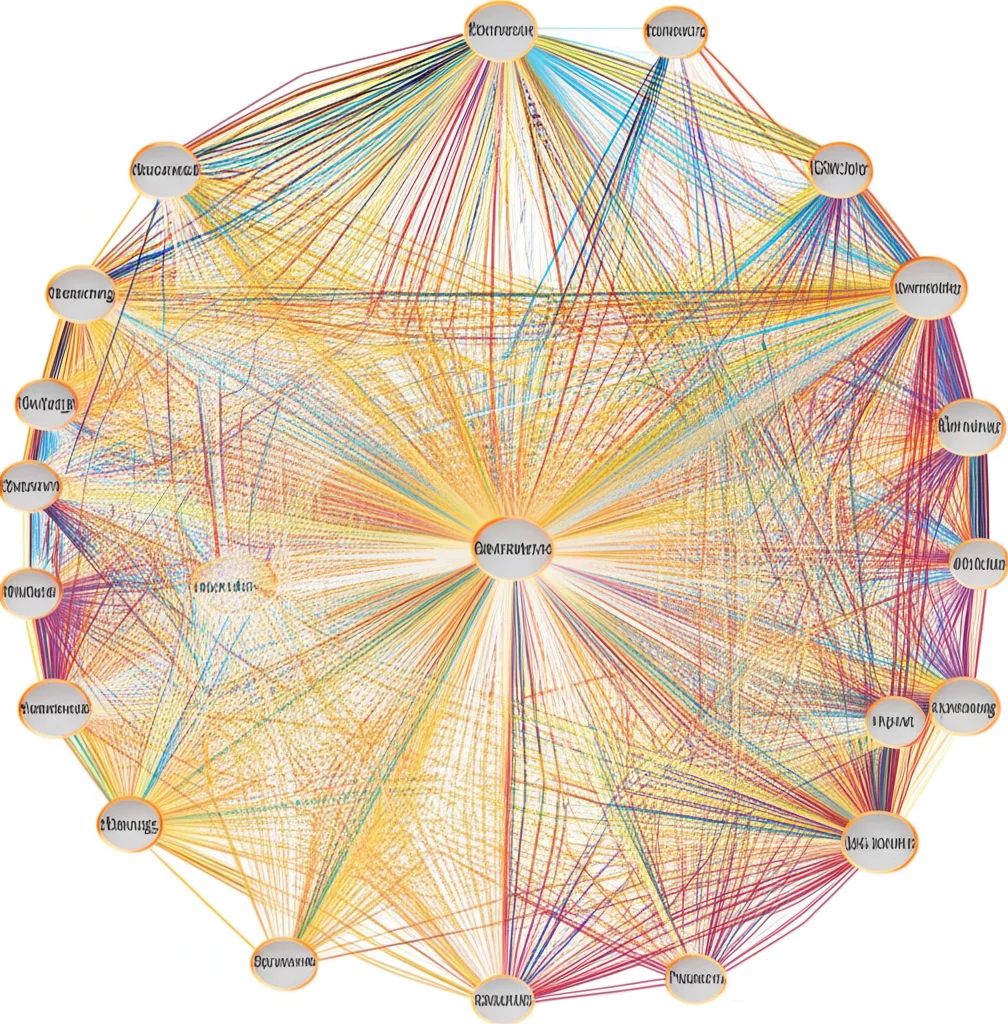

Next, we checked if the tool made sense to people (face validity) and if it covered all the important stuff it was supposed to (content validity). We asked patients and experts for their feedback. Then came the heavier lifting: checking the *construct validity*. This is about seeing if the items on the scale group together in a way that makes theoretical sense. We used two main statistical techniques: Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) and Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA). EFA helps us discover the underlying structure (how many factors or dimensions of distress the items measure), and CFA helps us confirm that structure with a separate group of patients. We also used something cool called network analysis (EGA) to visualize how the different distress items connect to each other.

We didn’t stop there! We checked for *convergent validity* (does it correlate with things it *should* correlate with?) and *discriminant validity* (does it *not* correlate too strongly with things it *shouldn’t*?). We also looked at *reliability* – basically, how consistent the tool is. We used measures like Cronbach’s alpha and McDonald’s omega for internal consistency (do the items within a factor hang together?) and tested if scores were stable over time (test-retest reliability). Finally, we checked for *measurement invariance* across gender, to see if the scale works the same way for men and women.

What We Discovered: The Two Faces of Distress

So, what did we find? Our patients had a mean age of about 43, and a bit over half were women. The average total CDI score was around 30.8. Interestingly, we saw some differences: women tended to have slightly higher distress scores than men, married participants scored higher than single ones, and folks with less education also had higher scores. Age had a weak positive link, meaning slightly older patients tended to have slightly higher distress, but it wasn’t a strong connection.

The big news from the factor analysis (EFA) was that the items didn’t just measure one big blob of distress. Instead, they grouped nicely into two main factors, explaining almost 70% of the variation in scores. We started with a 12-item version but ended up with a solid 10-item scale after removing two items (“Being physically restricted” and “Thinking about dying”) that didn’t quite fit the structure in our sample.

The two factors we identified were:

- Existential and Emotional Distress: This factor captures feelings like lacking purpose, feeling lonely, being emotionally exhausted, withdrawing from people, having changes in usual roles, and thinking “I will never be the same again.” It really gets at the deep emotional and identity challenges heart disease brings.

- Uncertainty and Maladaptive Coping: This one is about struggling to deal with stress, not knowing what the future holds, having difficulty concentrating, and feeling like you’re not getting clear directions from your doctor on managing your condition. It highlights the challenges of navigating the practical and cognitive aspects of living with heart disease when things feel uncertain.

Our Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) confirmed that this two-factor, 10-item structure fit the data really well.

The network analysis gave us a cool visual, showing how these items are connected. “Thinking I will never be the same again” seemed to be a really central item, connecting to many other feelings of distress. Items related to future uncertainty and loneliness also clustered together strongly.

And the reliability checks? Thumbs up all around! The internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha, McDonald’s omega) was strong for both factors, meaning the items within each factor hang together well. The test-retest reliability was also excellent, showing that if someone’s distress level doesn’t change, their score on the CDI is likely to stay consistent over time. We also confirmed that the scale works pretty much the same way for both men and women, which is important for fair assessment.

So, What Does This All Mean for Patients and Care?

Here’s the practical takeaway: We now have a validated, reliable tool – the 10-item Farsi CDI-SF – that healthcare providers in Iran can confidently use to measure cardiac distress in patients with heart disease. This is a big deal because it allows them to:

- Get a deeper understanding of a patient’s emotional and psychological state, beyond just basic anxiety or depression screening.

- Identify patients who are struggling with specific aspects of distress, like feeling isolated or overwhelmed by uncertainty.

- Tailor psychological support and interventions to address these specific challenges, making care more effective and culturally sensitive.

- Integrate psychological assessment into routine cardiac care and rehabilitation programs.

- Ultimately, help patients cope better, improve their quality of life, and potentially even improve their physical health outcomes by addressing the mental burden of heart disease.

It’s like finally having the right map to navigate the emotional landscape of heart disease for this population.

Every Study Has Its Quirks (and What’s Next)

Of course, like any study, ours had a few limitations. We relied on patients reporting their own feelings, which can sometimes be influenced by wanting to give the “right” answer. Our sample was also from specific clinics using convenience sampling, so the results might not perfectly reflect *every* heart patient in Iran. We also didn’t do detailed interviews to see exactly how patients understood each question, which could be helpful for cultural adaptation. And while we showed the CDI measures cardiac distress consistently, we didn’t check if higher scores actually predict things like future hospitalizations or recovery speed – that’s something for future studies!

But despite these points, our findings are a solid step forward. They confirm that the Farsi CDI-SF is a robust tool for assessing cardiac distress in this population.

Wrapping Up

In a nutshell, this study gives healthcare providers in Iran a much-needed, culturally appropriate tool to measure the unique psychological distress experienced by patients living with heart disease. By understanding these emotional challenges better, we can offer more targeted support, improve patient well-being, and hopefully make the journey with heart disease a little less daunting. It’s exciting to think about how this validated tool can help improve care and research in the region.

Source: Springer