Cracking the Code: Predicting Colon Cancer Immunotherapy Response with CAF Genes

Alright folks, let’s chat about something super important in the fight against cancer, specifically colon cancer. We all know it’s a tough one, sadly ranking high up there globally in terms of how common and how deadly it is. For years, surgery and chemotherapy have been the main weapons in our arsenal, and they’re still vital, especially for earlier stages. But for those more advanced cases, things get trickier.

Then came immunotherapy, specifically immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs). Remember back in 2013 when SCIENCE magazine called cancer immunotherapy the top scientific breakthrough? It totally revolutionized how we think about treating many cancers. It’s like teaching the patient’s own immune system to fight the bad guys – the cancer cells. Pretty cool, right?

But here’s the catch, and it’s a big one: these amazing therapies don’t work for everyone. Even in colon cancer patients who have a specific genetic marker (called MSI-H/dMMR), which usually suggests they *should* respond well, the success rate isn’t 100%. Far from it, actually. So, we’re left with this urgent need to figure out *who* is most likely to benefit from immunotherapy and, just as importantly, who might not. This helps doctors make better decisions and avoid giving potentially ineffective treatments that can still have side effects.

The Tumor Microenvironment: A Cast of Characters

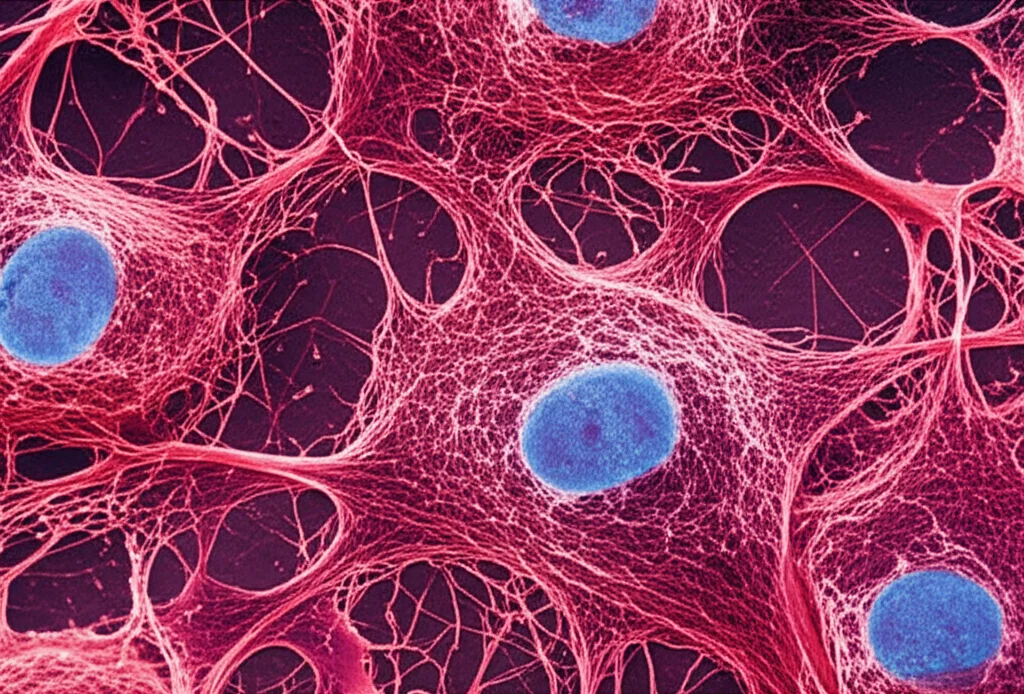

Turns out, the tumor isn’t just a clump of rogue cancer cells. It lives in its own little world, a complex neighborhood called the Tumor Microenvironment (TME). Think of it as a bustling city surrounding the tumor, filled with different types of cells, blood vessels, and a whole bunch of other stuff like the extracellular matrix (ECM) – basically, the scaffolding that holds tissues together.

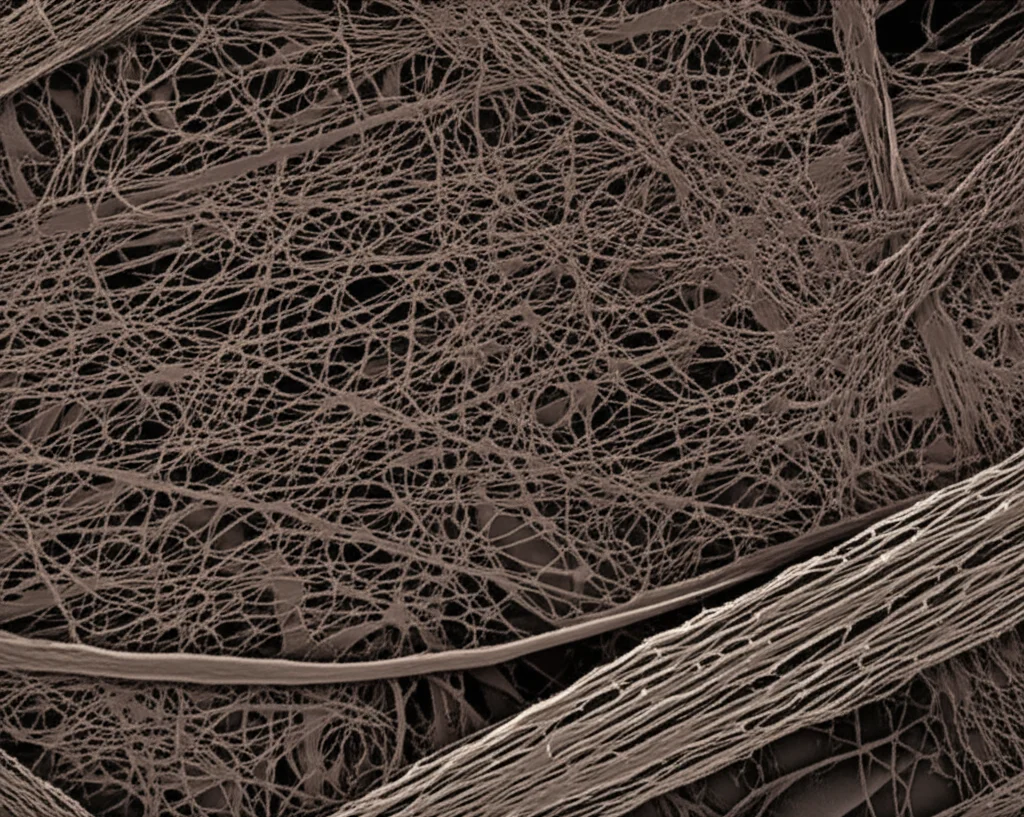

Among the key players in this TME are these characters called Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts, or CAFs for short. And let me tell you, they’re quite the influencers. Most studies point to CAFs as promoters of tumor growth. They’re like the architects of the TME, remodeling that ECM scaffolding. But they don’t just build; they also seem to build barriers! This reshaped ECM can actually act like a physical wall, making it hard for those crucial immune cells (the ones we want to attack the cancer) to get in and do their job. This essentially helps the cancer hide from the immune system – a process called immune escape.

Not only do CAFs build walls, but they also seem to send out signals that suppress the immune response. They can express molecules that put the brakes on T cells, and they secrete chemicals that dampen the anti-tumor activity of various immune cells. In colon cancer specifically, they’ve been linked to shutting down Natural Killer (NK) cells, another important type of immune cell.

Because CAFs are so involved in creating this immune-suppressive environment, we had a hunch: maybe, just maybe, the amount of CAF infiltration in a colon cancer tumor could tell us something about how well immunotherapy might work. If there are lots of CAFs, maybe the immune system is too suppressed for the therapy to be effective.

Hunting for CAF-Related Genes

So, our mission was clear: find a way to measure CAF abundance and see if it predicts immunotherapy response. We decided to dive into the vast ocean of publicly available data – specifically, gene expression data from colon cancer samples in databases like TCGA and GEO.

We used some pretty clever computational tools (R packages called “EPIC” and “MCPcounter”) to estimate the amount of CAF infiltration in these samples based on their gene expression profiles. Once we had these “CAF infiltration scores,” we used a technique called Weighted Gene Co-expression Network Analysis (WGCNA). This method is like finding cliques in a social network, but for genes. It helps us identify groups of genes that tend to be expressed together and are highly correlated with a specific trait – in our case, the CAF infiltration score.

We did this gene network analysis on samples from both the TCGA and GEO databases. Then, we looked for the genes that were consistently identified as being strongly related to CAFs in both datasets and using both scoring methods. It was quite satisfying to see that the genes identified by both “EPIC” and “MCPcounter” largely overlapped! After all that sifting, we ended up with a list of 84 genes that seem to be highly associated with CAFs in colon cancer.

What do these 84 genes do? We ran some analyses (GO and KEGG enrichment) to find out. Unsurprisingly, they were heavily involved in functions related to fibroblasts and, crucially, the extracellular matrix (ECM) – things like “extracellular matrix organization” and “collagen fibril organization.” This totally aligns with what we know about CAFs remodeling the tumor environment. They were also linked to pathways like “PI3K-Akt signaling” and “ECM-receptor interaction,” which are known players in cancer progression and cell communication.

Building and Testing Our Predictive Model

With our list of 84 CAF-related genes, the next step was to build a model that could use the expression levels of these genes to predict something useful. We wanted a model that could essentially give a “risk score” reflecting the level of CAF infiltration and, hopefully, predict immunotherapy response.

We used a statistical method called LASSO regression, which is great for selecting the most important genes from a larger list and building a predictive formula. We trained this model using the TCGA data and then tested its performance on an independent dataset from GEO (GSE39582) to make sure it wasn’t just good at predicting for the data it learned from (avoiding overfitting).

After the LASSO magic, we landed on a lean, mean model based on just four CAF-related genes: VEGFC, QKI, VIM, and ITGA5. The model calculates a “risk score” based on the expression levels of these four genes in a tumor sample.

We checked if this risk score actually reflected CAF abundance. And guess what? It did! In both the training and validation datasets, a higher risk score from our model was strongly correlated with higher CAF infiltration scores calculated by those initial software tools. We also looked at other known CAF-related genes from previous studies, and they were significantly more expressed in the high-risk group identified by our model. Plus, we validated using another database (CCLE) that our four model genes are indeed highly expressed in fibroblasts compared to colon cancer cells. All signs pointed to our risk score being a solid indicator of CAF abundance.

Predicting Immunotherapy and Chemo Response

Now for the really exciting part: can this risk score predict how patients will respond to immunotherapy? We divided the patients in both our training and validation cohorts into high-risk and low-risk groups based on our model’s score.

We used a tool called TIDE (Tumor Immune Dysfunction and Exclusion) which predicts immunotherapy response. The results were striking! In both datasets, the low-risk group had significantly lower TIDE scores (which suggests a better response) compared to the high-risk group.

We then looked at the expected response rates to immunotherapy. In the training group, the expected effective rate was a whopping 68% in the low-risk group versus just 24% in the high-risk group. The validation group showed similar numbers: 64% vs. 26%. That’s a massive difference!

To quantify how well our model predicts this, we looked at the AUC (Area Under the Curve) values, which measure a model’s predictive accuracy. Our model achieved an AUC of 0.780 in the training set and 0.774 in the validation set. These numbers are pretty good, and even slightly better than some previous models built for predicting survival based on CAF genes. This suggests our model is doing a decent job at predicting immunotherapy response specifically.

But what about chemotherapy? We also used a tool to predict sensitivity to common colon cancer chemo drugs like oxaliplatin, 5-fluorouracil, and irinotecan. Interestingly, the low-risk group showed significantly higher sensitivity to oxaliplatin compared to the high-risk group. For the other two drugs, there wasn’t a significant difference. This aligns with other research suggesting that CAFs can contribute to resistance to certain chemotherapy drugs, including oxaliplatin.

Digging Deeper into the Microenvironment

To understand *why* the high-risk group responds poorly, we looked closer at the tumor microenvironment and immune cell infiltration. Using tools like ESTIMATE and CIBERSORT, we scored the stromal (connective tissue) and immune components of the TME and analyzed the types of immune cells present.

As expected, the high-risk group had significantly higher stromal scores (consistent with more CAFs) and lower immune scores compared to the low-risk group. When we looked at specific immune cells, we found that the low-risk group had significantly higher infiltration of plasma cells and CD4 memory T cells. The high-risk group, on the other hand, showed significantly higher infiltration of M0 macrophages and neutrophils – cell types often associated with suppressing anti-tumor immunity and promoting tumor growth. This picture fits perfectly with the idea that high CAF infiltration creates a “cold,” immune-suppressed tumor environment that resists immunotherapy.

We also revisited the pathway analysis (GSEA) based on our high and low-risk groups. The high-risk groups in both datasets consistently showed enrichment in pathways directly linked to CAFs and ECM remodeling, like “collagen-containing extracellular matrix” and “ECM-receptor interaction.” The low-risk groups, however, showed more diverse and less consistently CAF-related pathways. This further reinforces that our model effectively identifies patients with high CAF infiltration.

We even did a more detailed pathway analysis (ssGSEA) and found that several ECM-related pathways, including “ECM-receptor interaction” and “focal adhesion,” were strongly correlated with our risk score. The correlation coefficients were quite high (above 0.8 in both cohorts!), again highlighting the tight link between our model, CAF infiltration, and ECM remodeling.

What Does This All Mean?

So, what’s the takeaway from all this data crunching?

- First off, we successfully built a gene signature model based on just four genes (VEGFC, QKI, VIM, ITGA5) that does a really good job of reflecting how much CAF is in a colon cancer tumor.

- More importantly, this model shows promising potential for predicting how well colon cancer patients might respond to immunotherapy. Patients flagged as “high-risk” by our model seem to have a significantly lower chance of benefiting from these therapies compared to those in the “low-risk” group.

- This prediction ability holds true in both the dataset we used to build the model and an independent validation dataset, which makes us more confident in the results.

- The findings also support the growing evidence that CAFs are major players in creating an immune-suppressive environment in colon cancer, making tumors less responsive to immune attacks.

- Interestingly, the high-risk group also seems less sensitive to oxaliplatin, a common chemo drug, suggesting CAFs might also contribute to chemoresistance.

This study suggests that looking at CAF infiltration levels could be a really useful way to help doctors decide if immunotherapy is the best first step for a colon cancer patient. For those identified as high-risk by our model, it might be better to consider other treatment options first to avoid the potential risks and costs of immunotherapy when the chances of success are lower.

Looking Ahead

Of course, this is a bioinformatics study based on analyzing existing data. While the results are consistent and validated across datasets, the real test comes when we translate this into clinical practice. We need to see if this model holds up when used prospectively with actual patients.

Another practical point is that our current model requires genetic sequencing to get the gene expression levels, which isn’t always easy or widely available everywhere. Our research team is already thinking about the next step: could we use a simpler method, like immunohistochemistry (IHC), to measure the protein levels of these four genes? That would be much more convenient for routine clinical use and could make this predictive tool accessible to more patients.

In conclusion, we’re pretty excited about this CAF gene signature model. It seems to be a reliable way to gauge CAF abundance and offers a valuable tool for predicting immunotherapy response in colon cancer. It reinforces the role of CAFs as immunosuppressors and opens the door for further exploration into using CAF levels as a guide for personalized treatment decisions. The journey continues, but this feels like a solid step forward!

Source: Springer