Bend It, Don’t Break It: How Twisting Superconductors Unlocks Cool New Physics!

Hey there, science enthusiasts! Ever wondered what happens when you take something as famously finicky as a superconductor and, well, bend it? You might think it’d just complain and stop working, and sometimes, yeah, that happens. But it turns out, giving these materials a bit of a twist or a bend – what we call bending-strain – can actually unlock some seriously cool and unexpected physics. We’re not just talking about breaking points; we’re talking about fundamentally changing how superconductivity behaves, and it’s got some electrifying (pun intended!) implications, especially for the world of superconducting spintronics.

So, What’s the Big Deal with a Little Bend?

Alright, so when you deform a superconducting wire or a thin film, you’re introducing strain. For a long time, the main concern was that this strain would mess with the critical current – the maximum current a superconductor can carry without resistance – and if you push it too far, bye-bye superconductivity. But here’s where it gets interesting. Recent studies have shown that this bending-strain, or curvature-induced strain as it’s sometimes called, isn’t just a party pooper. It can actually be a powerful tool, especially when the superconductor is cozying up next to another material.

The magic ingredient here seems to be something called effective spin-orbit coupling (SOC). Now, SOC is usually a property of certain materials (heavy metals, for instance) or engineered structures. But it turns out, just by bending a material, you can create an *effective* SOC. Why is this cool? Well, SOC is a key player in manipulating electron spins. In conventional superconductors, we mostly deal with what are called s-wave, even-frequency, spin-singlet correlations. Think of these as pairs of electrons spinning in opposite directions, all neat and tidy. But for spintronics – where you want to use electron spin for information processing – you really want to generate spin-polarized triplet correlations, where the electron spins can be aligned. And guess what? This curvature-induced SOC is a dab hand at converting those singlets into triplets! Suddenly, we can get these desirable spin-polarized superconducting states from abundant and versatile materials, without needing fancy magnetic multilayers or materials with strong intrinsic SOC. Just a little bit of geometry!

Getting a Bit Technical: How Strain Shakes Up Superconductivity

Let’s dive a little deeper, shall we? We’re focusing on what we call ‘clean, conventional superconductors’ – your garden-variety elements or alloys that have been studied for ages. When you introduce bending-strain, this effective SOC gets to work and starts to mix things up. It actually coaxes the superconductor to develop even-frequency p-wave triplet pairings. And these aren’t just any triplets; they can be both spin-polarized (where the spins have a preferred direction) and unequal-spin. This isn’t just a surface effect either; these new pairings pop up throughout the entire superconductor.

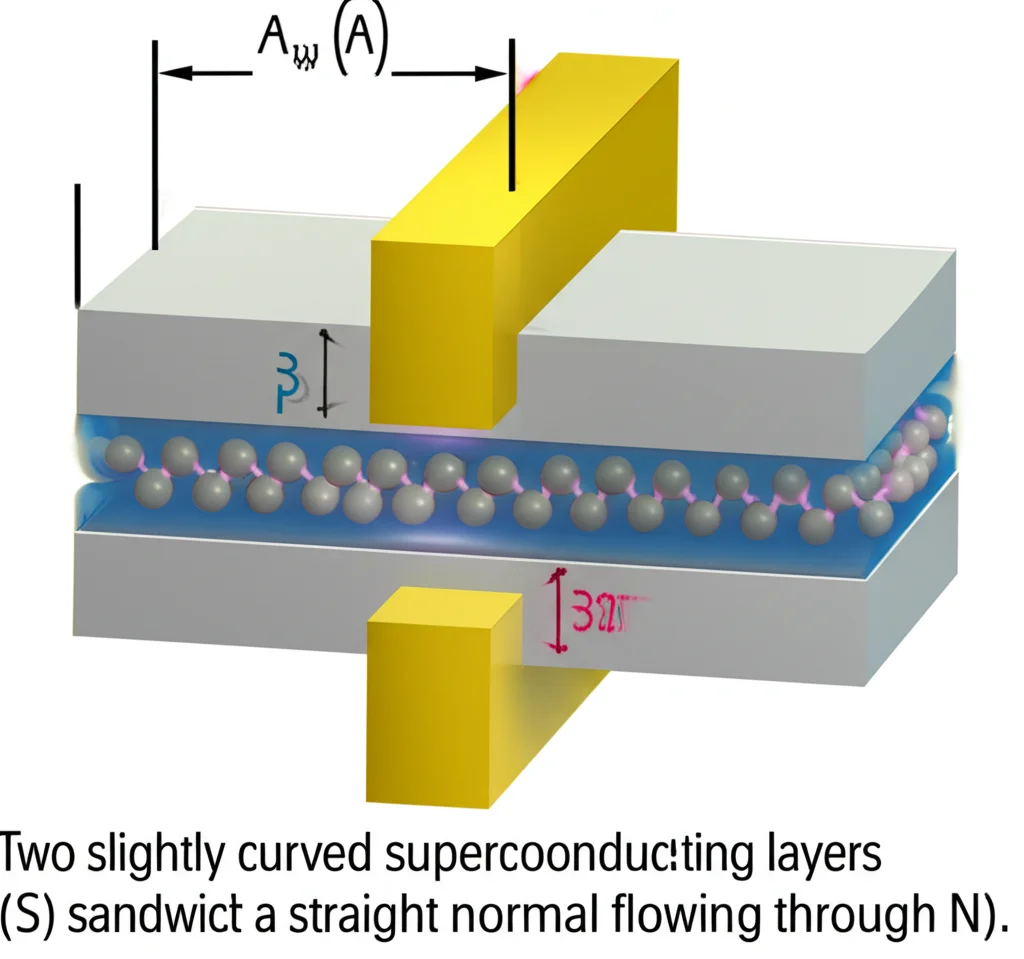

To figure all this out, we often turn to the trusty Bogoliubov-de Gennes framework. It’s a mathematical toolkit that lets us model what’s happening to the electrons and their pairings under these new conditions. Imagine a thin film being bent (like in the conceptual Fig. 1 of the original paper, with its tangential, normal, and binormal directions, and showing red for tensile and blue for compressive strain). This bending creates an asymmetry, and that’s what the SOC latches onto.

As you might expect, if you keep increasing the strain, the original s-wave superconductivity (the ‘normal’ kind) starts to weaken. This is a bit like what happens if you crank up a Rashba SOC in a superconductor. But as the s-wave part diminishes, these p-wave triplets, both the unpolarized ones (we call them ({{mathcal{P}}}_{uparrow downarrow }^{s})) and the spin-polarized ones (({{mathcal{P}}}_{sigma }^{b})), start to make their presence known. It’s a delicate balance, and the thickness of the film plays a role too. Thinner films can actually handle more curvature for the same surface strain, leading to stronger effective SOC. If the strain gets too high, though, everything eventually gives up the ghost.

The emergence of these p-wave states due to bending is pretty neat, especially because it highlights how the geometry of the system, even in thin films, can lead to novel effects that you wouldn’t necessarily predict from just looking at one-dimensional systems.

When Superconductors Meet Normal Metals: The SN Bilayer Story

Okay, so we’ve seen what happens to a lone superconductor under strain. But things get even more fascinating when we interface this strained superconductor (S) with a plain old normal metal (N) – creating an SN bilayer. You know about the proximity effect, right? It’s where superconducting properties can ‘leak’ into an adjacent normal metal.

Even without any strain, just having an interface between a conventional s-wave superconductor and a normal metal does something interesting: it breaks translational symmetry and can create odd-frequency p-wave singlets in the normal metal. These are purely due to something called Andreev reflections at the interface.

Now, let’s throw bending-strain into the superconductor part of the mix. The S-layer now has its mixed s-wave and p-wave character (({{mathcal{S}}}_{0}) + ({{mathcal{P}}}_{uparrow downarrow }^{s}) + ({{mathcal{P}}}_{sigma }^{b})), and these characteristics start to seep into the normal metal. But that’s not all! The interface itself, especially since the N-layer isn’t strained and thus has no curvature-induced SOC, acts as another source of symmetry breaking. This leads to the generation of additional odd-frequency pairings in the normal metal, like an odd-frequency s-wave triplet (({{mathcal{S}}}_{uparrow downarrow }(tau ))) and an odd-frequency p-wave singlet (({{mathcal{P}}}_{0}^{b}(tau ))).

The really cool part? The magnitudes of all these different induced pairings – both the even-frequency ones coming from the strained S and the odd-frequency ones popping up at the interface and due to strain – can be tuned by adjusting the applied strain! Imagine having a knob that lets you dial in different types of superconducting correlations. This could be done through mechanical means, thermoelectric effects, piezoelectric actuators, or even light if you use a photostrictive substrate. Talk about control!

The Superconducting Sandwich: SNS Junctions and Spin Surprises

Let’s take it one step further and make a sandwich: two strained superconductors (S) with an un-strained, uncurved normal metal (N) in between. This is your classic SNS Josephson junction. Usually, we talk about charge currents flowing across these junctions when there’s a phase difference between the two superconductors. But hold onto your hats, because with bending-strain in the S-layers, something else happens: a superconducting spin current can flow across the junction!

Now, spin current isn’t always a conserved quantity, especially if SOC is around messing with spin. But in our setup, the normal metal in the middle is straight and has no SOC. So, any spin current flowing through it is conserved in that region. We’ve found that the strain *alone* in the superconductors can induce this spin current. And it gets even wilder: this spin current can undergo what’s called a 0-π transition. This means that by tuning the strain (or the length of the normal metal), you can actually flip the direction of one of the components of the spin current (specifically, the component aligned in the binormal direction, Jb).

These 0-π oscillations are well-known in Josephson junctions that have a ferromagnetic material as the weak link. But here, we’re seeing it in a simple SNS junction, with the “magnetic” effect being mimicked by the strain-induced SOC! This suggests that strain is acting on the normal metal in a way similar to how a Zeeman interaction (from a magnetic field) would. So, you can potentially generate a pure spin current just by bending the superconductors. At low strain, the spin current might be mostly polarized in the tangential direction (Js), but after this 0-π transition, the binormal component (Jb) can take over.

Spin Currents, Magnetization, and Why We’re Excited

So we have this strain-induced spin current. What else comes with it? Well, when you have a charge current and SOC, you often get spin accumulation – a buildup of net spin. In our SNS junctions, the charge current (Josephson current) combined with the effective SOC from the strained superconductors leads to a strain-induced magnetization in the normal metal. This is reminiscent of the Edelstein effect. And, because the spin current can switch direction with strain (that 0-π transition), this induced magnetization can also switch its sign! You can literally flip the magnetization in the normal metal by tweaking the bend in the superconductors.

Think about it: we’re generating and controlling spin currents and magnetization in a non-magnetic material using purely mechanical strain on adjacent conventional superconductors. No external magnetic fields are needed, no intrinsically p-wave superconductors. This is all happening because of the interplay between the effective SOC from bending and the interfacial effects that rotate these proximity-induced correlations. The thin-film nature of the system is crucial here, as it allows for certain terms in the theoretical description that are key to these effects.

The Spintronics Dream: Bending Towards the Future

This is where things get really exciting for fields like superconducting spintronics and quantum logic circuits. The ability to control spin currents and magnetization with nanomechanical strain opens up a whole bunch of possibilities:

- Controllable superconducting qubits? Maybe!

- New types of memory devices? Could be!

- A superconducting diode effect (where current flows more easily in one direction than the other) induced by strain alone? It’s on the table!

We’ve shown that even modest amounts of strain, typically less than 1% (which is good because materials get brittle at cryogenic temperatures), can achieve these major effects. And while current tech for dynamically applying strain (like piezoelectric actuators) is often limited to this range, it’s enough to play with. The thickness of the superconducting film also matters. Thicker films can support superconductivity at higher strains, but the effective SOC might be different because the curvature changes through the film’s depth.

Peeking Over the Horizon: What’s Next?

Of course, this is just scratching the surface. There are so many more questions to explore!

- What if we include the p-wave pairings themselves in the self-consistency calculations? Could they become the dominant type of superconductivity at high strains?

- What about non-uniform curvatures, like an S-shaped junction? We’d expect the spin magnetization to behave differently, perhaps even cancel out if the curvatures are opposite.

- How does this all interact with other types of SOC, like intrinsic Dresselhaus SOC in the normal metal, or Rashba SOC from a substrate or gating? More control knobs!

And we’ve only talked about conventional superconductors. Imagine applying these ideas to unconventional materials. For chiral p-wave superconductors, bending-strain might split the Fermi surface in interesting ways, potentially leading to the emergence of exotic things like chiral Majorana edge states. For multiband superconductors, deforming the electronic bands with strain could have profound effects, maybe even helping to stabilize superconductivity in high magnetic fields.

We’ve also assumed that the strain is small enough not to mess too much with the fundamental electron-phonon interaction that causes superconductivity in the first place. For really large strains, that might not be true, and understanding that boundary is another avenue for future research.

In a nutshell, it looks like simply bending or straining conventional superconductors can be a surprisingly powerful way to generate and control some pretty exotic superconducting states and spin phenomena. It’s a fantastic example of how revisiting well-known materials with a new perspective (and a bit of a twist!) can lead to exciting new physics and potential applications. Who knew being under a bit of stress could be so productive for superconductors?

Source: Springer Nature