Unpacking the Beef with Bovine Cysticercosis in Upper Egypt

Hey there, let’s talk about something super important for anyone who enjoys a good steak or is just generally interested in where our food comes from. We’re diving into a study that looked at slaughtered cattle in Upper Egypt, specifically in the Aswan province, and found something called *Cysticercus bovis*. Now, that might sound a bit technical, but stick with me, because it’s got some real implications for food safety and, honestly, the wallets of folks in the cattle business.

So, What Exactly is *Cysticercus bovis*?

Alright, picture this: there’s a tapeworm called *Taenia saginata* that lives in the small intestine of humans. Humans are the main hosts, the ‘definitive’ ones, if you like. Now, this tapeworm produces eggs, and these eggs can get into the environment. When cattle munch on grass or drink water contaminated with these eggs – yep, you guessed it – they pick them up. The eggs hatch inside the cattle, and the larvae travel through the bloodstream and settle in the muscles, forming cysts. These cysts are what we call *Cysticercus bovis*. Cattle are the ‘intermediate’ hosts in this cycle.

The big worry? If a human eats raw or undercooked beef containing these live cysts, they can develop taeniasis, which is basically getting the adult tapeworm in their gut. While often mild, it’s still a parasitic infection, and frankly, nobody wants that! Beyond the human health aspect, finding these cysts in cattle carcasses is a major headache for the meat industry. Infected carcasses can be condemned entirely, or at best, the infected parts are removed, and the rest has to be frozen for a long time to kill the parasites. This all adds up to significant economic losses.

Peeking Inside Aswan’s Slaughterhouses

This study I’m telling you about took a close look at cattle slaughtered in several main slaughterhouses across Aswan province in Upper Egypt between July 2023 and April 2024. The team checked out a massive number of cattle – 47,763, to be exact! They weren’t just doing a quick glance; they used routine inspections, but also backed it up with more detailed stuff like looking at tissue under a microscope (histopathology) and even using fancy molecular techniques like PCR to confirm the parasite’s DNA.

The goal was simple: figure out how common *C. bovis* is in these cattle destined for our plates and understand what factors might be linked to the infection. Aswan is an interesting place for this kind of study because it’s a hot area and handles a lot of cattle, including those imported from other African countries.

What Did We Find? The Numbers Game

Out of those nearly 48,000 cattle inspected, about 2.27% showed macroscopic *C. bovis* cysts during the routine checks. Now, let’s break that down a bit.

- Local Egyptian breeds had an infection rate of 1.94%.

- Imported cattle, mainly from Sudan and Ethiopia, showed a slightly higher rate at 2.36%.

Interestingly, the study found that the prevalence of *C. bovis* was significantly linked to a few things about the cattle:

- Age: Older and adult cattle were more likely to be infected than younger ones. This makes sense, right? The longer they live, the more chances they have to be exposed.

- Sex: Males had a higher prevalence than females, which might be related to the types of cattle being slaughtered (more males for meat production, especially imported ones).

- Body Condition: Cattle in poorer body condition were also more likely to be infected. This could suggest that the infection is chronic and might contribute to the animal losing weight over time.

The study also noted that while there wasn’t a huge statistical difference between all the slaughterhouses, Abu Simbel and Aswan slaughterhouses saw the majority of positive cases. Abu Simbel handles a lot of those imported cattle, which could be a factor, maybe due to conditions during transport or their origin countries having higher infection rates.

Where Did the Cysts Hide? Predilection Sites

When they found cysts, they looked at where they were located in the carcass. It turns out the preferred spots differed a bit between the local and imported cattle:

- In local breeds, the heart was the most common spot, found in 64% of infected local cattle.

- For imported breeds, the masseter muscles (that’s in the jaw) and the tongue were the big winners, affected in 92.00% and 90.23% of infected imported cattle, respectively.

They saw different types of cysts too. Some were *viable* – clear, fluid-filled sacs with the larval parasite inside, bulging from the muscle. Others were *degenerating* or non-viable – more like yellow, calcified nodules that felt gritty when cut. The good news, relatively speaking, was that most infected carcasses had localized lesions, meaning the cysts were only in one or a few organs, not spread throughout the whole animal. This suggests the severity wasn’t always super high in these specific cases.

Getting Technical: Microscopy and PCR

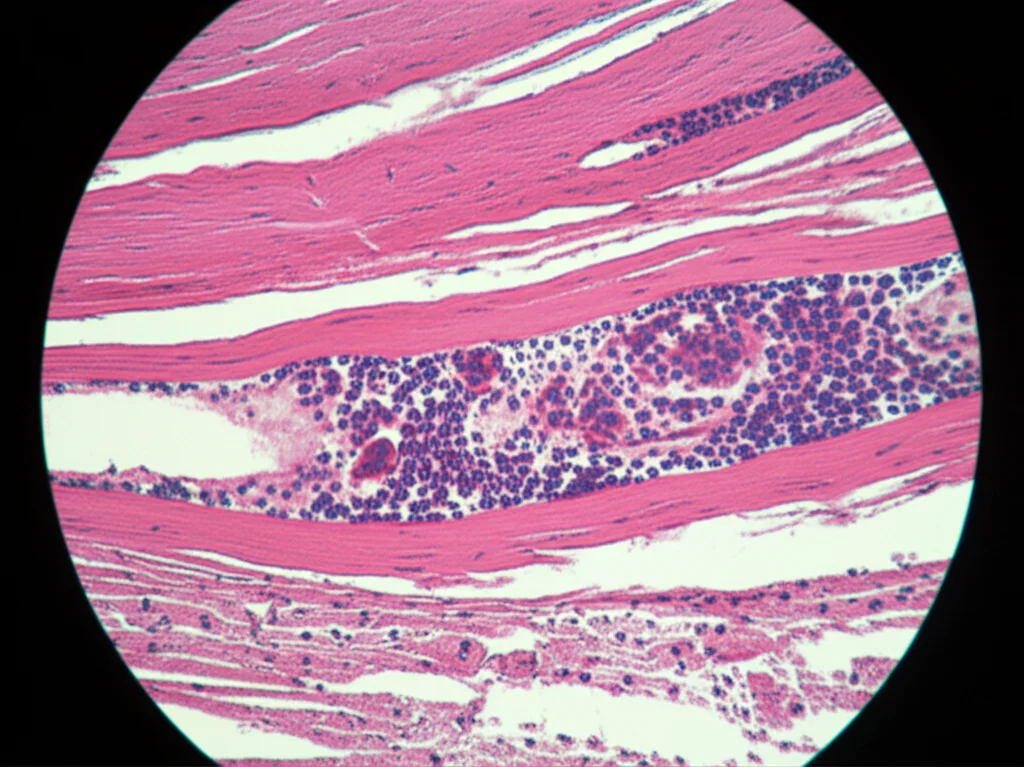

To really confirm what they were seeing, the researchers used more advanced tools. Under the microscope (histopathology), they looked at tissue samples containing the cysts. They saw the fluid-filled cavities with the parasite inside, surrounded by a fibrous capsule. Crucially, they also saw signs of the body fighting back – lots of inflammatory cells, especially eosinophils and macrophages, and changes in the muscle tissue itself, sometimes looking degenerated or even necrotic (dead tissue). This microscopic view helps confirm it’s *C. bovis* and not something else that might look similar macroscopically.

Then came the molecular test, PCR. This is like looking for the parasite’s unique genetic fingerprint. They tested samples for a specific gene called *HDP2* that belongs to *C. bovis*. Every single one of the suspected cyst samples they tested came back positive for this gene. This is a big deal because visual inspection alone can be unreliable; other things can cause similar-looking lesions. PCR provides a much more accurate confirmation.

So, What Does This All Mean for Us?

Okay, let’s put it together. This study confirms that *C. bovis* is present in slaughtered cattle in Aswan, Upper Egypt, and while the overall prevalence rate of 2.27% might seem relatively low compared to some historical numbers or other regions, it’s still there. It means there’s a risk of human infection if meat isn’t handled and cooked properly.

The finding that imported cattle had a slightly higher prevalence is important. It highlights that diseases don’t respect borders, and the health status of animals coming into a country is crucial. Factors like age, sex, and body condition being linked to infection give us clues about which animals might be at higher risk.

Interestingly, the researchers noted that the prevalence they found was lower than some previous studies in Aswan. They hypothesize this could be due to increased consumer awareness about food safety, stricter regulations from the Egyptian authorities, and maybe even the fact that meat prices have gone up, leading to fewer cattle being slaughtered overall. However, they also acknowledge that some slaughtering might still happen outside official abattoirs, which is harder to track and control.

The study really underscores the limitations of relying solely on visual inspection. While it’s the first line of defense, it can miss cases or misidentify lesions. Combining it with techniques like histopathology and especially PCR makes detection much more accurate and reliable.

Looking Ahead: A One Health Approach

The implications here go beyond just inspecting meat. This is a classic example of a “One Health” issue – where the health of humans, animals, and the environment are all connected. To truly tackle *C. bovis* and prevent human taeniasis, we need a coordinated effort.

This means:

- Improving sanitation and preventing human sewage from contaminating cattle grazing areas.

- Regular surveillance in cattle, not just in Aswan but across Egypt, using reliable diagnostic methods.

- Implementing risk classification systems to target control efforts effectively.

- Educating consumers about the importance of cooking meat thoroughly to kill any potential parasites.

The study authors strongly support this One Health strategy. It’s about protecting human health, preventing economic losses for farmers and the meat industry, and ensuring the overall health of the animal population.

While this study provided valuable insights, particularly confirming the parasite’s presence with molecular methods and highlighting the situation in Aswan, it also points to areas for future research. Looking at other types of slaughtered animals, including more slaughterhouses, and perhaps using more advanced molecular techniques like DNA sequencing could give an even clearer picture of the situation.

Ultimately, this research reminds us that food safety is a continuous effort, requiring vigilance from farms to slaughterhouses to our own kitchens. Understanding parasites like *C. bovis* and implementing robust control measures is key to keeping our food supply safe and supporting the livelihoods of those involved in cattle production.

Source: Springer