ARHGDIB: Glioma’s Master of Disguise and Prognostic Puzzle

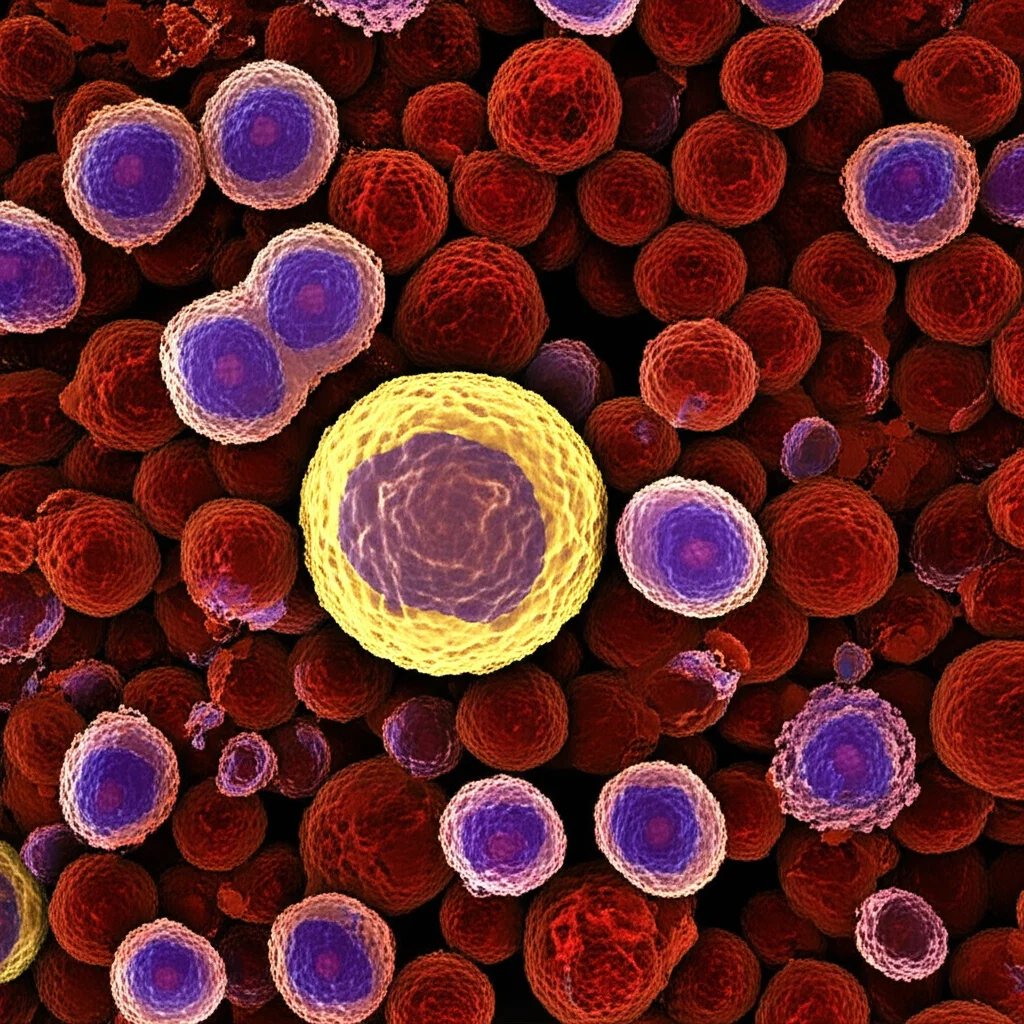

Hey there! Let’s talk about something pretty serious: gliomas. If you’ve heard the term, you know they’re tough brain tumors. They’re malignant, they’re aggressive, and honestly, current treatments often hit a wall. Why? Well, a big part of the problem lies in their ‘neighborhood’ – the tumor microenvironment. Think of it as the soil the tumor grows in. In glioma, this soil is often super immunosuppressive, meaning it actively works to shut down your body’s natural defenses, the immune system. This makes it really hard for treatments, especially immunotherapies, to do their job effectively. It’s a major reason why the prognosis for patients, particularly those with the most aggressive type, glioblastoma (GBM), remains stubbornly poor.

Now, scientists like us are always on the hunt for new clues, new pieces of the puzzle that might help us understand these tumors better and find ways to fight back. One such piece that’s popped up in research is a protein called ARHGDIB (sometimes known as RhoGDI2). This protein is a bit of a regulator, controlling other small proteins called Rho family GTPases, which are involved in all sorts of cell behaviors – how they move, grow, and change shape. ARHGDIB has been seen playing different roles in other cancers, sometimes helping tumors spread, sometimes slowing them down. It’s also been hinted at being involved in remodeling that tricky tumor microenvironment.

But what about glioma? Its role there has been a bit of a mystery. So, we decided to dive deep and figure out what ARHGDIB is up to in these brain tumors. We pulled data from big public databases, looked at tissue samples from patients we collected ourselves, and even did some work in the lab with cells. We wanted to see where ARHGDIB shows up, what it correlates with, and if it could give us any hints about how a patient might fare or how the tumor is manipulating its surroundings.

ARHGDIB: A Potential Bad Sign?

So, what did we find? Using fancy techniques like qPCR and immunohistochemistry (basically, looking at gene and protein levels in tissues), alongside analyzing tons of data, we saw something pretty clear: ARHGDIB is *way* more expressed in glioma tissues compared to normal brain tissue. And it wasn’t just a little bit higher; it was significantly elevated. What’s more, the higher the grade of the glioma (meaning the more aggressive it is), the higher the ARHGDIB expression tended to be. This was consistent across multiple datasets and our own patient samples. It seems like ARHGDIB might be a marker for the more malignant, nastier versions of glioma.

This got us thinking: if it’s higher in more aggressive tumors, does it predict how patients will do? We used statistical methods like Kaplan–Meier survival analysis (which creates those survival curves you might see in research) and LASSO-Cox regression (a way to find the most important factors). The results were pretty striking. Patients with high levels of ARHGDIB expression consistently had worse outcomes – shorter overall survival, disease-specific survival, and progression-free interval. Across multiple independent cohorts, high ARHGDIB was linked to a significantly poorer prognosis. It really does look like ARHGDIB could serve as a potential biomarker, a warning sign for adverse outcomes in glioma patients.

We even built a risk score model based on ARHGDIB and other related genes, and it was quite good at predicting patient prognosis. Patients categorized into a “high-risk” group based on this score had significantly shorter survival times compared to the “low-risk” group. This held true in training sets, validation sets, and external cohorts. It reinforces the idea that ARHGDIB, or genes linked to it, are telling us something important about the tumor’s behavior and the patient’s future.

Messing with the Neighbors: The Immune Microenvironment

Given that ARHGDIB expression is so tied to how aggressive the tumor is and how long patients survive, we figured it must be doing something important to drive that progression. We looked at which biological pathways were active in tumors with high ARHGDIB. Interestingly, many of the enriched pathways were related to the tumor microenvironment and immune modulation, things like “angiogenesis” (new blood vessel formation, often abnormal in tumors), “inflammatory response,” and key signaling pathways like “TNFα-NF-kappaB signaling.” These pathways are known players in shaping that tricky tumor neighborhood.

Using algorithms to estimate the composition of the tumor microenvironment, we found that gliomas with high ARHGDIB expression had higher “immune scores” and “stromal scores.” This suggests that ARHGDIB might be influencing both immune cells and the non-immune connective tissue cells within the tumor. We then drilled down into specific immune cell types. And this is where it gets really interesting.

Our analysis showed that high ARHGDIB expression was positively correlated with the infiltration of certain types of immune cells – specifically, the ones known to suppress the immune response. Think M2 macrophages and neutrophils. These aren’t the immune cells that fight the tumor; they’re the ones that often help it grow and evade detection by the *real* anti-tumor cells. Conversely, we saw negative correlations with some anti-tumor cells like activated NK cells and naive CD4 T cells. It seems ARHGDIB is somehow involved in recruiting or promoting the presence of these immunosuppressive players in the glioma microenvironment.

Further investigation, including single-cell sequencing data (which lets us look at individual cells within the tumor), immunohistochemistry, and immunofluorescence (seeing where proteins are located), showed that ARHGDIB expression patterns were very similar to CD163, a well-known marker for M2 macrophages. In fact, we saw ARHGDIB and CD163 often hanging out together in the same areas of the tumor tissue. This strongly suggested a link between ARHGDIB and these M2 macrophages.

Immunity on Pause: How ARHGDIB Might Help Glioma Hide

The body’s fight against cancer involves a complex sequence of events called the cancer immunity cycle. It’s like a multi-step dance where immune cells recognize, activate, travel to, infiltrate, and finally kill cancer cells. Our analysis suggested that in gliomas with high ARHGDIB, several steps of this crucial cycle seemed to be dampened or impaired. This included steps related to releasing tumor antigens, activating immune cells, and recruiting certain types of immune cells that *would* fight the tumor.

This aligns perfectly with the idea that ARHGDIB is promoting an immunosuppressive environment. If you’re bringing in the immune suppressor cells (M2 macrophages, neutrophils) and hindering the steps needed for anti-tumor immunity, you’re essentially putting the immune response on pause, giving the tumor a free pass to grow and spread.

What about immunotherapy? These treatments often target immune checkpoint molecules, which are like brakes on the immune system. We looked at the correlation between ARHGDIB and these checkpoint molecules (like PD-1, PD-L1, CTLA-4, etc.). Guess what? High ARHGDIB expression was strongly and positively correlated with most of these immune checkpoints. This suggests that tumors with high ARHGDIB might have these ‘brakes’ fully engaged, potentially limiting the effectiveness of checkpoint inhibitor therapies.

This connection to immune checkpoints and the overall dampening of the immune cycle in high-ARHGDIB tumors is a big deal. It implies that ARHGDIB isn’t just a passive marker; it might be actively contributing to the tumor’s ability to evade the immune system. This could be why standard immunotherapies haven’t been as successful in gliomas as they have in some other cancers.

Lab Proof: ARHGDIB’s Influence on Macrophages and Glioma Cells

To really test the idea that ARHGDIB in macrophages is bad news for glioma, we took it to the lab. We worked with immune cells (specifically, a type that can turn into macrophages) and boosted their ARHGDIB levels. Then, we co-cultured these ARHGDIB-overexpressing macrophages with glioma cells. We wanted to see if the macrophages, now potentially influenced by high ARHGDIB, would affect the glioma cells.

The results were pretty clear. When glioma cells were grown alongside macrophages with high ARHGDIB, the glioma cells showed increased proliferation (they grew more) and increased migration (they moved more). This supports our findings from the patient data and bioinformatics. It suggests that ARHGDIB, particularly when expressed in macrophages within the tumor microenvironment, can directly promote the aggressive behavior of glioma cells. It seems to do this by inducing the macrophages to become more M2-like, a state where they secrete factors (like TGF-β) that help the tumor.

Hope for the Future: Biomarker and Target?

So, where does this leave us? Our study paints a picture where ARHGDIB is significantly overexpressed in glioma, especially the more aggressive types. This high expression is a strong indicator of a poor prognosis for patients. Crucially, we found that ARHGDIB seems to be a key player in shaping that hostile, immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment. It appears to recruit and promote the polarization of immune cells like M2 macrophages, which then help the tumor grow and evade the immune system. It’s also linked to the activation of immune checkpoints, potentially limiting the effectiveness of current immunotherapies.

This is pretty big news because it suggests a couple of exciting possibilities:

- Prognostic Biomarker: Measuring ARHGDIB levels in a patient’s tumor might help doctors better predict how the disease will progress and tailor treatment strategies accordingly.

- Therapeutic Target: Since ARHGDIB seems to be actively contributing to the problem (by creating that immunosuppressive environment and boosting tumor growth), it could potentially be a target for new therapies. Maybe we could develop drugs that block ARHGDIB or interfere with its ability to influence macrophages.

Imagine combining therapies that target ARHGDIB or the M2 macrophages it influences with existing treatments like chemotherapy, radiotherapy, or even immune checkpoint inhibitors. This kind of combination approach might be what’s needed to overcome the current limitations in treating glioma and finally improve patient outcomes.

Now, like any good scientific study, ours has limitations. We did a lot of work with data and cells in the lab, but the next crucial step is to see if these findings hold up in living systems, like animal models, to really understand the systemic effects and how ARHGDIB interacts in the complex environment of the brain. We also need to dig even deeper into the exact molecular mechanisms – how exactly does ARHGDIB tell macrophages to become M2-like? Is it through pathways like NF-κB or Rho GTPases, as hinted by the data? Pinpointing these steps is key for designing effective drugs.

Also, while we focused on M2 macrophages (because the data pointed strongly there), the tumor microenvironment is a complex mix of cells. ARHGDIB might be influencing other cell types too, and we need to explore those interactions. And relying heavily on existing datasets means we need to be mindful of potential biases or differences between patient populations or specific glioma subtypes (like IDH-mutant vs. wild-type, which have different immune landscapes).

But despite these limitations, our findings provide compelling evidence that ARHGDIB is a significant player in glioma’s aggressive behavior and its ability to suppress the immune system. It’s more than just a protein; it seems to be a conductor orchestrating the tumor’s hostile microenvironment. Unraveling its role offers exciting new avenues for research and, hopefully, for developing more effective, personalized treatments for patients battling this challenging disease.

Source: Springer