Arctic Time Travel: Muddy DNA Reveals Ancient Marine Mammal Secrets

Hey There, Fellow Science Enthusiast!

Ever look at the vast, icy landscapes of Northern Greenland and wonder what life was like there thousands of years ago? Especially for the incredible marine mammals that call it home? Figuring out the deep history of these ocean dwellers is tricky business. They spend their lives at sea, so finding their fossils is, well, about as rare as spotting a unicorn on an iceberg! This makes it super hard to build a long-term picture of how their populations and distributions have changed over time, especially in response to big climate shifts like those that happened after the last ice age.

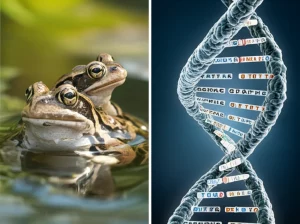

Enter the Muddy Time Machine: Sedimentary Ancient DNA!

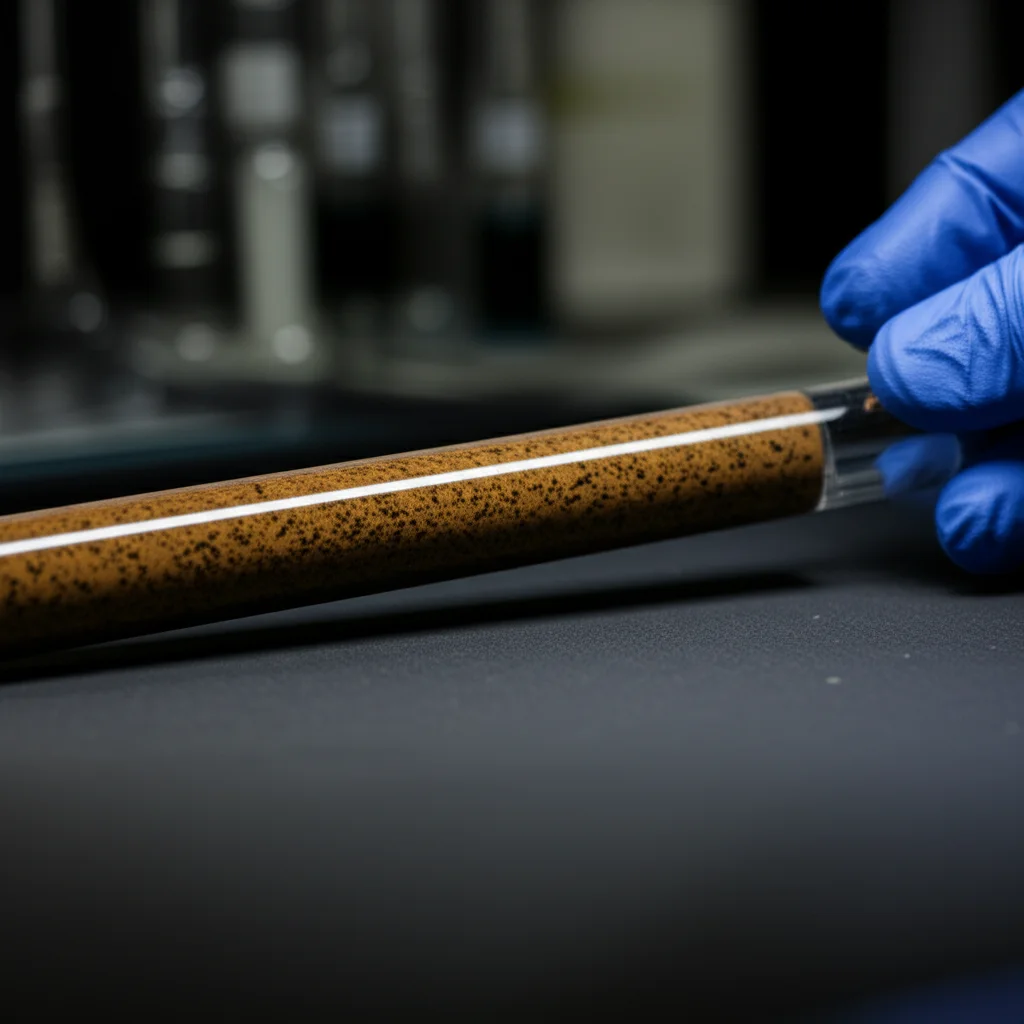

But guess what? Science keeps finding clever ways to peek into the past! The latest cool tool in the paleo-detective kit is something called sedimentary ancient DNA, or sedaDNA. Think of it like tiny genetic footprints left behind in the mud and sediment at the bottom of the ocean over millennia. As marine mammals swim, shed skin cells, or, sadly, pass away, their DNA sinks and gets preserved in the layers of sediment. By pulling up cores of this sediment and analyzing the ancient DNA within, we can reconstruct who was where, and when!

I recently dove into a fascinating study that did just this around Northern Greenland. Scientists collected four marine sediment cores from different spots: Melville Bay, Hall Basin, Lincoln Sea, and North-East Greenland. These cores essentially act as layered archives of history, stretching back about 12,000 years, covering the entire Holocene period since the last major glaciation. By combining advanced DNA sequencing techniques with data from other environmental clues preserved in the sediment (like tiny fossils called foraminifera, and chemical markers for sea ice and ocean productivity), they pieced together an amazing story.

The Big Melt and the First Arrivals

What did they find? Well, one of the most striking things I saw was how closely the appearance of marine mammals in the sediment record lined up with the retreat of the massive ice sheets at the start of the Holocene. As the ice pulled back, opening up new marine habitats, the animals moved in! And get this – the sedaDNA detected some species *much* earlier than any physical fossil remains found in the region. For ringed seals, for example, the DNA evidence showed they were there up to 2,000 years before the oldest known fossil! This really highlights the power of sedaDNA to fill in gaps where fossils are scarce.

The study suggests that ringed seals, being super adapted to life around sea ice, were likely some of the first marine mammals to colonize these newly ice-free (or seasonally ice-free) areas after the ice sheets retreated. It makes sense – they’re tough little guys built for the cold!

The Holocene Warm-Up: A Northward Migration

One of the most intriguing periods the study looked at was the Early-to-Mid Holocene, roughly 10,000 to 5,500 years ago. This was a time when regional air temperatures were significantly warmer than today – in some places up to 6°C higher than the pre-industrial average! As you might expect, this warmer period had a big impact on the environment:

- Glaciers retreated dramatically.

- Sea ice extent and thickness decreased.

- Warmer ocean currents, like the West Greenland Current, intensified, bringing warmer, saltier water northwards.

And guess what the marine mammals did? They followed the warmth and the open water! The sedaDNA from the Melville Bay core, in particular, showed something really cool: species that today are considered temperate or low-arctic (meaning they usually hang out further south or only visit the far north seasonally) were present in this more northerly region at densities detectable in the sediment. We’re talking about species like:

- Fin whales

- Minke whales

- Orcas (killer whales)

- Hooded seals

- Harp seals

- Beluga whales

Finding DNA from fin whales, for example, at 75° N is pretty remarkable, as they aren’t typically seen that far north along the west coast of Greenland today. This suggests a significant northward shift in their distribution ranges during this warmer period. The study’s statistical analysis confirmed that air temperature and sea-ice conditions were significant drivers of these community changes. It seems the increased influence of warmer Atlantic waters and reduced sea ice created suitable habitat further north for these species.

![]()

What’s fascinating is the possibility that during this time, you might have had communities of marine mammals that look quite different from what we see today – a mix of Arctic specialists and more temperate visitors coexisting. Though the sediment layers represent time spans of hundreds of years, so it’s hard to know if they were literally swimming side-by-side or if their presence fluctuated over shorter periods.

Cooling Down: The Later Holocene Shift

As the Holocene progressed into its later stages (roughly the last 5,000 years), the climate cooled again, and sea ice increased in many areas. The sedaDNA record reflects this shift. The study detected fewer marine mammal species overall during this cooler period compared to the warmer Early-to-Mid Holocene. This aligns with other evidence, like changes in mollusc species distributions and sediment characteristics, suggesting a decrease in the influence of warmer Atlantic waters and a return to colder conditions.

The data hints at a potential southward shift for some species during these colder times, similar to what’s been seen for bowhead whales during the more recent “Little Ice Age” cold snap. The picture becomes one of marine mammal distributions expanding north during warm phases and potentially retreating south during cold phases, following the availability of suitable, ice-influenced or ice-free habitat and food sources.

Unlocking the Far North and East Coast Secrets

The cores from the northernmost sites (Hall Basin and Lincoln Sea, near 82-83° N) provided unique insights into the “Last Ice Area” – a region expected to retain multiyear sea ice the longest under future warming. SedaDNA showed marine mammals, like ringed seals and narwhals, appearing in these areas shortly after the Nares Strait (the passage between Greenland and Ellesmere Island) opened up from being covered by glacial ice around 9,000 years ago. This again shows rapid colonization of newly available habitat.

Interestingly, the North-East Greenland core (around 79° N) told a slightly different story. This coast is heavily influenced by the cold East Greenland Current, which exports a lot of sea ice from the Arctic Ocean. The sedaDNA detections here were more sporadic and generally lower in abundance compared to the west coast sites. This suggests that despite some variability in past ocean conditions on the east coast, it has generally been less suitable habitat for a wide range of marine mammals over the last 10,000 years compared to the west coast, which benefits from the warmer West Greenland Current.

Why This All Matters Now

So, why should we care about where marine mammals swam thousands of years ago? Because the Arctic is warming incredibly fast today – much faster than the global average. Sea ice is disappearing rapidly, and ocean currents are changing. Understanding how marine mammal communities responded to past warming periods, like the Early-to-Mid Holocene, gives us crucial context for predicting how they might respond to the warming happening now and in the near future. This study provides a unique, long-term baseline dataset that wasn’t available before. It shows that past climate shifts caused significant changes in where these animals lived and which species were present in different areas.

The fact that temperate species moved north during a warmer past period is particularly relevant as we observe similar northward shifts happening today. Will Arctic specialists find refuge in places like the Last Ice Area? How will interactions between Arctic and incoming temperate species play out? These are big questions, and studies like this, using the incredible power of ancient DNA preserved in mud, give us vital clues from history to help us understand the present and prepare for the future.

Wrapping Up

Honestly, I find it absolutely mind-blowing that tiny fragments of DNA, buried in ocean mud for thousands of years, can tell us such a detailed story about ancient life and environmental change. This research is a fantastic example of how combining geology, genetics, and paleoclimate science can unlock secrets about our planet’s past. It reminds us that the Arctic ecosystem is dynamic and has responded to climate shifts before, but the speed and cause of current changes are unprecedented. Having this long-term perspective from the sedaDNA is invaluable for conservation efforts and managing marine life in a rapidly changing world.

Source: Springer