Unlocking the Mystery: Why ApoE4 Might Make You Feel More Pain

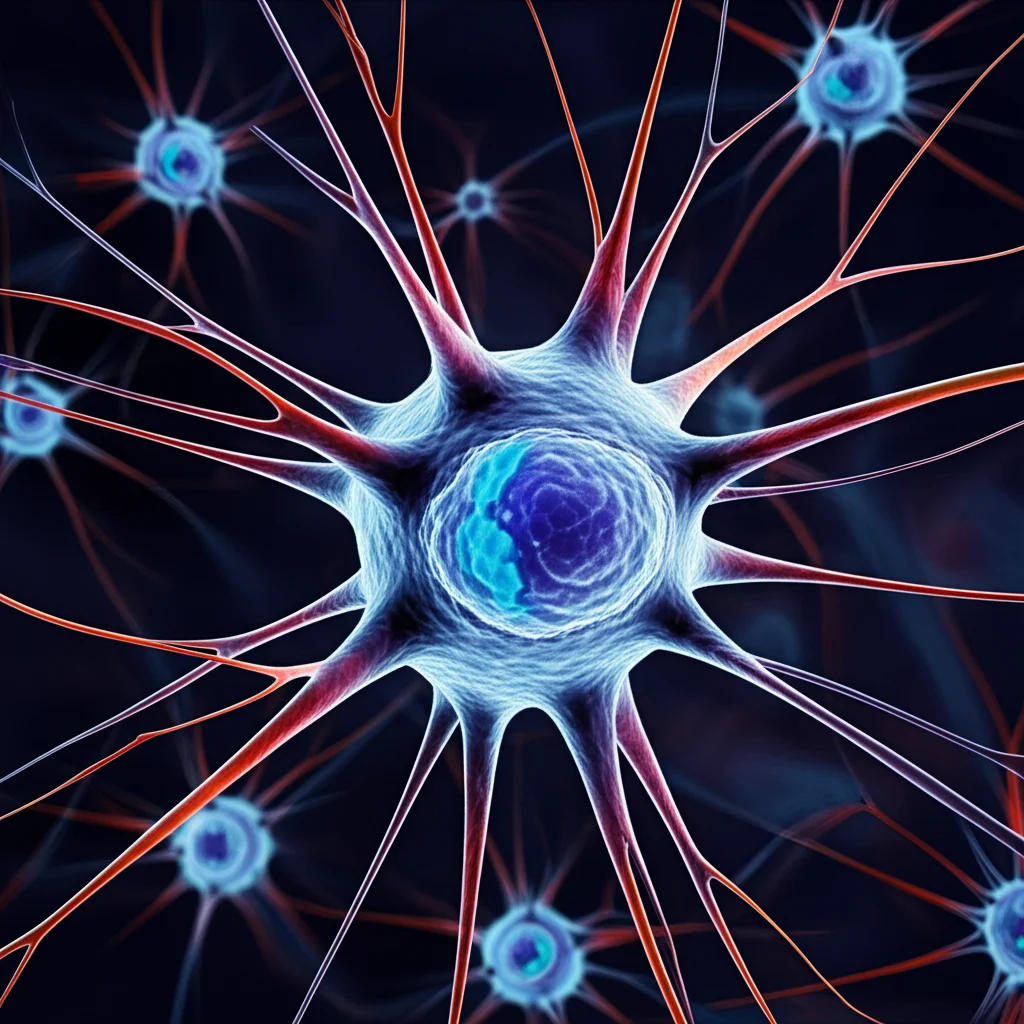

Hey there! Ever wondered why some folks seem to feel pain more intensely than others, especially when it comes to those stubborn, chronic types like neuropathic pain? You know, the kind that sticks around long after an injury should have healed? Well, we scientists are constantly digging into these mysteries, and we’ve stumbled upon something pretty fascinating involving a protein called ApoE and those amazing support cells in your brain and spinal cord, the astrocytes.

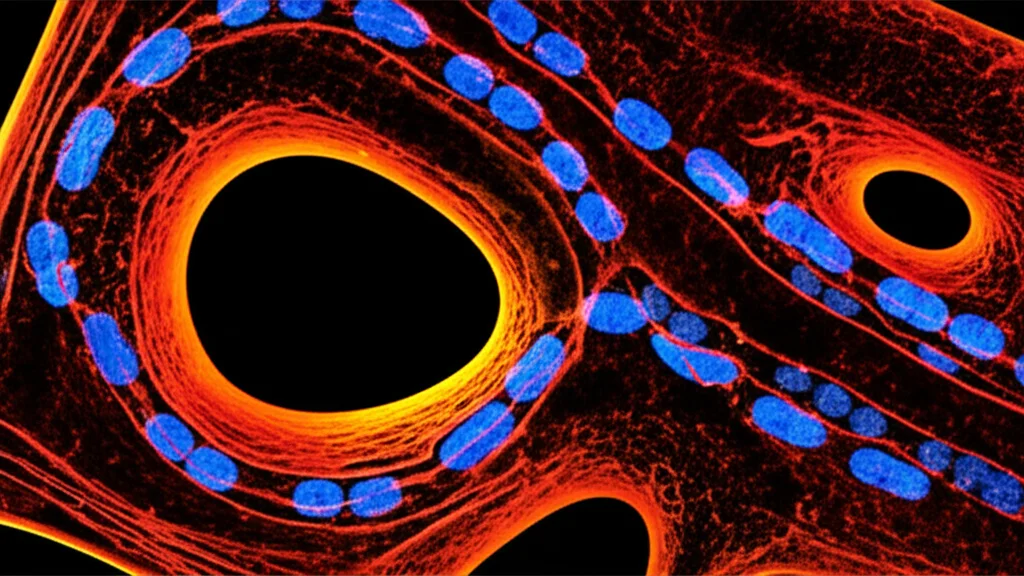

Neuropathic pain is a real tough cookie. It’s chronic, debilitating, and frankly, our current treatments aren’t always hitting the mark. We’ve known for a while that glial cells – the brain’s support crew, like astrocytes and microglia – play a huge role in amplifying pain signals in the central nervous system. Think of astrocytes as the main stagehands; they can really crank up the volume on pain by releasing inflammatory signals.

ApoE: More Than Just Cholesterol Transport

Now, let’s talk about ApoE. You might have heard of it because it’s involved in moving fats around your body, but it’s also a big deal in the brain, especially in astrocytes. Humans have a few versions (isoforms) of ApoE: ApoE2, ApoE3, and ApoE4. ApoE3 is the most common, found in about 79% of us. But ApoE4? That one’s linked to a higher risk of certain neurological conditions, most notably late-onset Alzheimer’s disease. It’s also been tied to more severe nerve damage in conditions like diabetes. This got us thinking: if ApoE4 is linked to other nerve-related problems, could it also influence how we experience neuropathic pain?

Until now, the connection between ApoE4 and neuropathic pain wasn’t super clear. So, we decided to dive in using some clever mouse models. These mice were engineered to express the human versions of ApoE3 or ApoE4. We gave them a type of nerve injury (called spared nerve injury, or SNI) that causes neuropathic pain, and then we watched how sensitive they were to touch – a standard way to measure this kind of pain.

ApoE4 Mice Feel the Burn More

What we saw was pretty intriguing. The mice with human ApoE4 (we call them ApoE4-TR mice) were *much* more sensitive to touch after the nerve injury compared to the ApoE3-TR mice. This wasn’t just a subtle difference; it was quite pronounced, showing up as early as 7 days post-injury and getting even more significant later on. We also used a fancy treadmill system called DigiGait™ that measures walking patterns objectively, and it confirmed that the ApoE4 mice showed behaviors indicative of greater pain.

To really nail down *where* this was happening, we looked at neuronal activity in the spinal cord, specifically in the area where pain signals come in (the dorsal horn). Using a technique called fiber photometry, we saw that neurons in the ApoE4 mice were much more excitable in response to pain stimulation. This lined up perfectly with their increased pain sensitivity.

Since ApoE is mainly found in astrocytes in the spinal cord, we suspected these cells were key players. To test this, we used another set of mice where we could *specifically* turn on human ApoE4 expression just in astrocytes in the spinal cord. Lo and behold, these mice also showed increased pain sensitivity after nerve injury, just like the full ApoE4-TR mice. This strongly suggested that astrocytic ApoE4 is a major contributor to this heightened pain response.

Okay, so ApoE4 astrocytes seem to be involved in cranking up the pain volume. But *how*? We figured it had something to do with inflammation, as that’s a known player in neuropathic pain and ApoE is linked to neuroinflammation. We measured inflammatory cytokines – those signaling molecules that can cause trouble – in the spinal cord. Sure enough, ApoE4 mice had significantly higher levels of key inflammatory cytokines like IL-6, IL-1β, and TNF-α after nerve injury compared to ApoE3 mice. We even saw this difference when we grew astrocytes from ApoE3 and ApoE4 mice in a dish and stimulated them with inflammatory signals – the ApoE4 astrocytes released more inflammatory factors.

The Plot Thickens: Spermidine Enters the Scene

ApoE is also involved in metabolism, so we wondered if metabolic differences might be playing a role. We took a deep dive into the metabolites present in the spinal cord of these mice after injury. Our analysis revealed distinct metabolic profiles between the ApoE3 and ApoE4 groups. Among the many differences, one metabolite really stood out: spermidine.

Spermidine is a type of polyamine, and it’s known to hang out primarily in astrocytes in the central nervous system. It’s like a cellular bodyguard, helping protect against oxidative stress and playing roles in cell function. Interestingly, we found that spermidine levels were lower in the spinal cord of ApoE4 mice compared to ApoE3 mice after nerve injury. Even under normal conditions, ApoE4 mice had slightly less spermidine, but the difference became more pronounced after the injury.

Spermidine: A Potential Therapy, With a Twist

Since spermidine was lower in the more pain-sensitive ApoE4 mice, we hypothesized that giving them spermidine might help. We started giving spermidine daily to both ApoE3 and ApoE4 mice after nerve injury, using two different doses.

The results were quite telling. With a high dose of spermidine, both ApoE3 and ApoE4 mice showed similar, significant pain relief. Their mechanical pain thresholds increased, and inflammatory cytokine levels in the spinal cord dropped to comparable levels. It seemed like spermidine was indeed helping to dampen the pain signals.

However, the low-dose group told a different story. While the low dose helped the ApoE3 mice significantly, it was much less effective in the ApoE4 mice. They still had lower pain thresholds and higher inflammatory cytokine levels compared to the ApoE3 mice receiving the same low dose. This suggested that ApoE4 carriers might need *more* spermidine to get the same benefit.

Why the difference in dosage? We looked at astrocytes in the lab again. We found that ApoE4 astrocytes seemed to have a harder time holding onto spermidine compared to ApoE3 astrocytes. When we gave them spermidine and then removed it from the medium, the ApoE4 astrocytes lost it faster. At high concentrations, they could keep taking it up from outside the cell, but their *retention* capacity seemed impaired. This limited retention likely explains why a higher dose is needed in ApoE4 mice – they just can’t keep as much of it inside the astrocytes where it’s needed.

Pinpointing the Molecular Pathway: NF-κB and NOS2

So, we have less spermidine in ApoE4 astrocytes, leading to more pain and inflammation. But what’s the exact molecular chain of events? We looked at the gene expression in the spinal cord of ApoE3 and ApoE4 mice after injury. We found hundreds of genes that were expressed differently, many involved in processes like lipid transport, oxidative stress, and nitric oxide production.

One gene that really stood out and was significantly upregulated in ApoE4 mice was Nos2. This gene makes an enzyme called iNOS (or NOS2) which produces nitric oxide (NO). iNOS is known to be ramped up in astrocytes during inflammation and is linked to increased pain sensitivity. We confirmed that both Nos2 gene expression and the resulting NO levels were higher in ApoE4 mice and in ApoE4 astrocytes in culture after inflammatory stimulation.

Given that spermidine levels were lower and Nos2 was higher in ApoE4 mice, we tested if spermidine could influence Nos2. Indeed, treating mice and astrocytes with spermidine reduced the levels of NOS2 and NO. This looked like a key part of how spermidine helps.

Next, we asked *how* spermidine might be regulating Nos2. Our gene analysis pointed towards a major cellular signaling pathway called NF-κB. This pathway is a master switch for inflammation. We found that in ApoE4 mice and astrocytes, the NF-κB pathway was more active after nerve injury or inflammatory stimulation. Crucially, spermidine treatment reduced this NF-κB activity. To confirm the link, we used a chemical that activates NF-κB (called PMA). When we activated NF-κB, it reversed the effect of spermidine, increasing NOS2 levels again. This strongly suggests that spermidine works, at least in part, by calming down the NF-κB pathway, which in turn reduces NOS2 and helps alleviate pain.

Putting It All Together: A Tailored Approach to Pain Relief?

So, here’s the picture we’re starting to paint: If you have the ApoE4 genetic variant, your astrocytes might have a harder time keeping enough spermidine inside them, especially after something like a nerve injury. This spermidine insufficiency contributes to increased inflammation and higher levels of the pain-promoting molecule NO (via the NF-κB/NOS2 pathway), making you more sensitive to neuropathic pain.

The good news? Spermidine supplementation shows promise as a way to combat this. The catch? Because of the retention issue in ApoE4 astrocytes, individuals with the ApoE4 variant might need a higher dose of spermidine to achieve the same level of pain relief as someone with ApoE3. This highlights the exciting possibility of tailoring pain treatments based on a person’s genetic makeup.

Of course, this is just one piece of the puzzle. There’s still more to explore, like whether these effects change with age (spermidine levels naturally decline as we get older) or how this mechanism plays out in different types of chronic pain. But these findings are a significant step forward, showing us that our genes, our glial cells, and even specific metabolites like spermidine are all intricately linked in shaping our experience of pain. It’s a complex dance, but understanding the steps brings us closer to finding better ways to help people who suffer from chronic pain.

Source: Springer