Winning the War Against Infection After Femoral Fracture Surgery

Hey there! Let’s chat about something pretty important in the world of fixing broken bones, specifically those nasty femoral shaft fractures. You know, the big thigh bone? When you break that, especially from something serious like a car crash or a big fall, surgery is usually the way to go to get things lined up and healing right. A super common method is called intramedullary nailing. Think of it like putting a sturdy rod right down the middle of the bone to hold it together.

The Nasty Problem: Postoperative Infections

Now, while nailing is great for stability, it does open the door to a potential nightmare: postoperative infections. Once bacteria get into that medullary cavity (the space inside the bone where the rod goes), it’s bad news. It can totally mess up healing, mean you’re in treatment forever, and often requires *more* surgeries. These bugs just love to hang out along the implant, spreading through the bone cavity. We’re talking localized infections, weird sinus tracts forming, and even bone death (osteomyelitis). It makes everything way harder to manage and can leave you with long-term issues with your leg.

Enter the Hero? Antibiotic-Impregnated Bone Cement

This is where something called Antibiotic-Impregnated Bone Cement (AIBC) comes into the picture, and honestly, it’s looking like a real game-changer. AIBC isn’t just a physical spacer to help hold things open; it’s designed to deliver a punch of antibiotics right where the infection is. This is crucial because getting enough antibiotics to the surgical site with just pills or IVs can be tough, especially when blood flow might be messed up by the injury itself. AIBC gives a sustained release, keeping those antibiotic levels high locally, which is key for wiping out bacteria and hopefully preventing those superbugs from showing up.

The idea of using AIBC, especially with femoral shaft fractures treated with nailing, has been bounced around and studied quite a bit. Results have been a bit mixed in the past – some studies showing big drops in infection rates, others just modest benefits. Its effectiveness really depends on a bunch of things: what kind of antibiotic is used, how long it keeps releasing, what specific bug is causing the trouble, and even the properties of the cement itself.

What We Did in Our Study

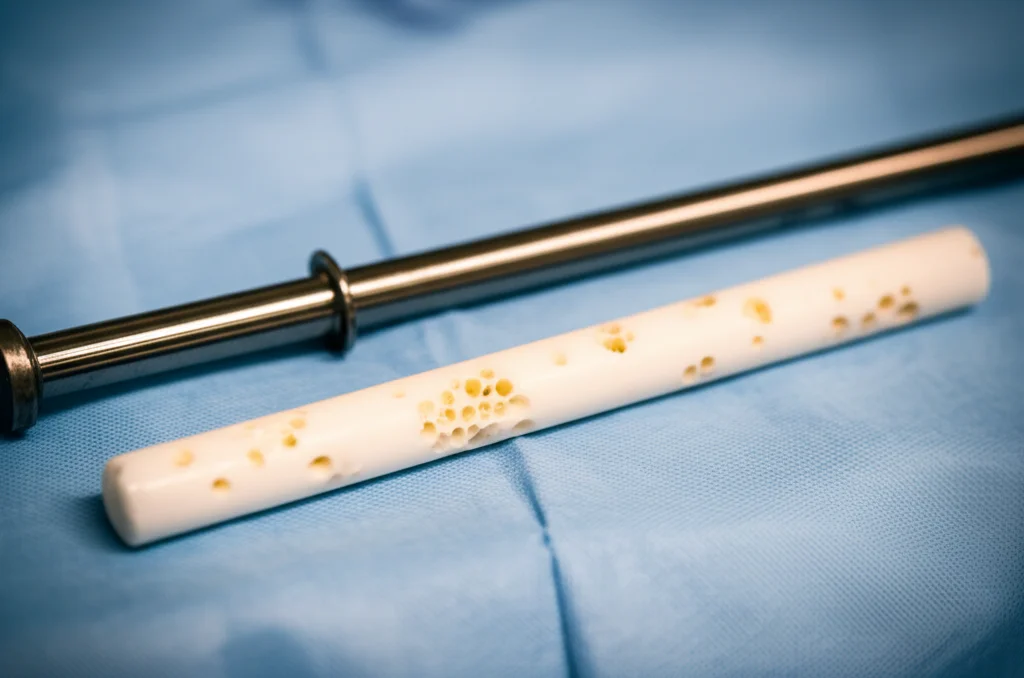

So, we decided to take a good look at this. We conducted a retrospective analysis right here at our place, checking out patients treated between January 2020 and January 2023. We focused on 40 patients who, unfortunately, developed postoperative infections after getting their femoral shaft fractures fixed with intramedullary nailing. Our treatment plan for them was pretty comprehensive: we surgically cleaned everything out (debridement), took out the original nail, reamed out the medullary canal (cleaned it out), and then put in AIBC rods specifically made with vancomycin.

We followed these patients for a full 12 months to see how things went. We were looking for a few key things:

- Did the infection come back?

- Did the bone heal properly?

- What happened with their inflammatory markers (like white blood cell count, ESR, CRP, procalcitonin)?

- How did their leg function and ability to do daily stuff improve?

Who Was In? (Our Patient Crew)

Our study group of 40 patients included 23 guys and 17 gals, ranging in age from 21 to 77, with the average age being about 43. Most injuries came from traffic accidents (21 cases), but also high falls (6) and slips (13). We had a mix of open fractures (23) and closed ones (17). Their BMI was pretty standard, averaging around 22. We also classified their osteomyelitis using the Cierny–Mader system: 33 were Type A hosts (pretty straightforward), and 7 were Type B (had other health issues like hypertension or diabetes). Anatomically, most were Type I (medullary infection), some combined with Type III (localized) or Type IV (diffuse). Nineteen patients even had chronic sinus formation, which tells you how tough these infections can be.

The Treatment Process: Getting Down to Business

Our treatment wasn’t just one thing; it was a multi-pronged attack. After removing the infected nail, we got serious about cleaning out the bone. We made a cortical window (a small opening in the bone) to get a good look and plenty of space. Then, we reamed the medullary canal using a drill slightly bigger than the old nail to really scrape out infected tissue. We flushed the cavity with tons of saline (3-5 liters!) using a pulsatile lavage system – think of it like a power wash for the bone – to get rid of debris and bacteria.

We also took tissue samples to figure out exactly which bacteria were causing the problem so we could pick the best antibiotics later. After cleaning and re-sterilizing, we got ready for the AIBC. If we knew the bacteria sensitivity beforehand, we chose the antibiotic based on that. If not, we mixed 40g of bone cement with 4g of vancomycin until it was a non-sticky paste. We molded this paste into rods, adding a Kirschner wire for strength and a thin wire to help with removal later. Once hardened, we smoothed out the rod and implanted it into the medullary canal.

Post-surgery, patients got IV antibiotics based on the culture results for three weeks, then switched to oral antibiotics. This whole plan was about keeping infection controlled, helping the bone heal, and preventing it from coming back.

Checking Up: 12 Months Later

We kept a close eye on everyone for a year. For bone healing, we checked X-rays for bridging and callus formation, felt for tenderness, and watched if they could move independently. For infection, we looked for any signs like fever, redness, swelling, pain, new sinus tracts, or weird lab results. Resolution meant all symptoms gone and lab tests back to normal.

We also measured inflammatory markers before treatment and six weeks after. We checked WBC, ESR, CRP, and procalcitonin. These are super important for seeing if the inflammation from the infection was calming down.

And crucially, we looked at how well they could use their leg and do everyday things before treatment and at the 12-month mark. We used scales like the Fugl-Meyer and Brunnstrom for motor function and ADL scales for daily activities. Higher scores on motor scales mean better function, while lower scores on ADL scales mean more independence – which is what we want!

The Results: Pretty Awesome, If We Do Say So Ourselves!

Okay, here’s the really exciting part. Out of all 40 patients, none showed any signs of the infection coming back during the entire 12-month follow-up. That’s a 100% success rate for controlling the infection! This really highlights how effective this combined approach was, with the AIBC playing a big part in keeping that local area clean.

And the bone healing? Also 100% success! All patients achieved complete osseous union within 12 months. This tells us that putting the AIBC in didn’t mess up the bone’s natural ability to heal. In fact, by controlling the infection, it likely created a much better environment for healing to happen.

Let’s talk about those inflammatory markers. They showed a significant drop after surgery. WBC went from a mean of 14.09 down to 8.36. ESR dropped from 64.60 to 26.36. CRP, a really sensitive marker, plummeted from 104.75 to just 11.62! And procalcitonin, which is great for bacterial infection risk, went from 1.81 down to a tiny 0.21. These numbers are a clear sign that the infection and the resulting inflammation were effectively managed.

But what about actually *using* the leg? Big improvements there too! The Fugl-Meyer score for lower limb motor function jumped from 13.80 before treatment to 30.24 after 12 months. The Brunnstrom scale also showed progress, going from 2.02 to 4.11. This means patients got a lot more control and function back in their legs.

And for daily life? The ADL scales showed great progress towards independence. The Physical Self-Maintenance Scale scores dropped from 20.03 to 8.23, meaning they needed less help with basic self-care. The Instrumental Activities of Daily Living Scale scores went from 30.67 to 9.32, showing they could handle more complex daily tasks on their own. These are huge wins for quality of life!

Why We Think It Works So Well

Postoperative infections after femoral nailing are a really tough nut to crack. Systemic antibiotics often struggle to get high enough concentrations right at the infection site without causing nasty side effects. AIBC changes the game by putting a high dose of antibiotics exactly where it’s needed. It acts like a local antibiotic factory, releasing the drug continuously. This targeted approach is super important, especially where blood supply might not be great. It hits the bugs hard and potentially reduces the chance of them becoming resistant.

Beyond the antibiotics, the cement itself might help. It fills the space left by the infection and removed nail, potentially preventing blood clots (hematomas) and dead space where bacteria love to grow. While the rod we used wasn’t primarily for structural support like the original nail, its presence likely helped maintain space and stability, which is good for both infection control and healing. The fact that all bones healed so well suggests the AIBC didn’t hinder bone growth; it might have even helped by keeping the environment clean and less inflamed. The cement could even act as a bit of a scaffold for new bone to grow onto.

The big drop in inflammation markers we saw is likely because the infection was effectively cleared. Less infection means less inflammation, both locally and throughout the body. Controlling inflammation is key for a smoother recovery and fewer complications. With infection and inflammation under control, patients can often get into rehab sooner and more aggressively, which is vital for getting motor function and daily activities back.

Putting It in Context (and Being Realistic)

Other studies have looked at antibiotic cement, often for chronic infections or non-healing fractures, showing good success rates. Our study is a bit different because we focused specifically on *early* postoperative infections after acute femoral shaft fractures treated with nailing. This is a distinct scenario with its own challenges. We also looked at functional recovery and inflammatory markers, not just infection control and healing, which gives a more complete picture.

Now, let’s be real, our study has limitations. It was a relatively small group (40 patients) and didn’t have a control group (patients with infection treated *without* AIBC) which makes it harder to say definitively that AIBC *caused* these great results, although the outcomes are highly suggestive. It was also done at just one center, so our specific surgical techniques and follow-up might be different elsewhere. The 12-month follow-up is good, but rare or delayed problems might show up later. We didn’t see any major complications, but minor things like temporary pain or swelling did happen. Since PMMA cement isn’t absorbed by the body, sometimes it might need to be taken out later if it causes irritation, though we didn’t see that here.

Also, how the antibiotic is mixed into the cement and how it’s released can vary and affect how well it works and if it’s safe. There’s always a theoretical risk of bacteria becoming resistant if the antibiotic levels aren’t consistently high enough over time.

So, while our results are super encouraging, we definitely need bigger, multi-center studies (like randomized controlled trials) with longer follow-ups. This will help confirm our findings, figure out the best antibiotic mixes, and keep an eye out for any long-term issues like resistance or cement problems.

The Takeaway

Based on what we saw, using medullary reaming and implanting antibiotic-impregnated bone cement rods after intramedullary nailing for femoral shaft fractures with postoperative infections looks incredibly promising. It was highly effective at preventing infection recurrence, led to excellent bone healing, significantly reduced inflammation, and helped patients regain motor function and independence in daily life. These results suggest this approach is a really valuable tool in orthopedic surgery and definitely worth considering for wider use.

Source: Springer