A Game Changer for Giant Birthmarks: Our BCL2 Therapy Breakthrough

Hey there! Let’s talk about something pretty significant we’ve been working on. You know those really large birthmarks, the kind kids are sometimes born with? They’re called Giant Congenital Melanocytic Nevi, or GCMN for short. They can be a real challenge, not just because of how they look, but because they carry a lifelong risk of turning into something serious, like melanoma. For years, the main options have been surgery or lasers, but honestly, they often don’t get the whole thing, especially the big ones, and can leave scars or just come back. We knew we needed a better way.

The Mystery of the Stubborn Nevus Cells

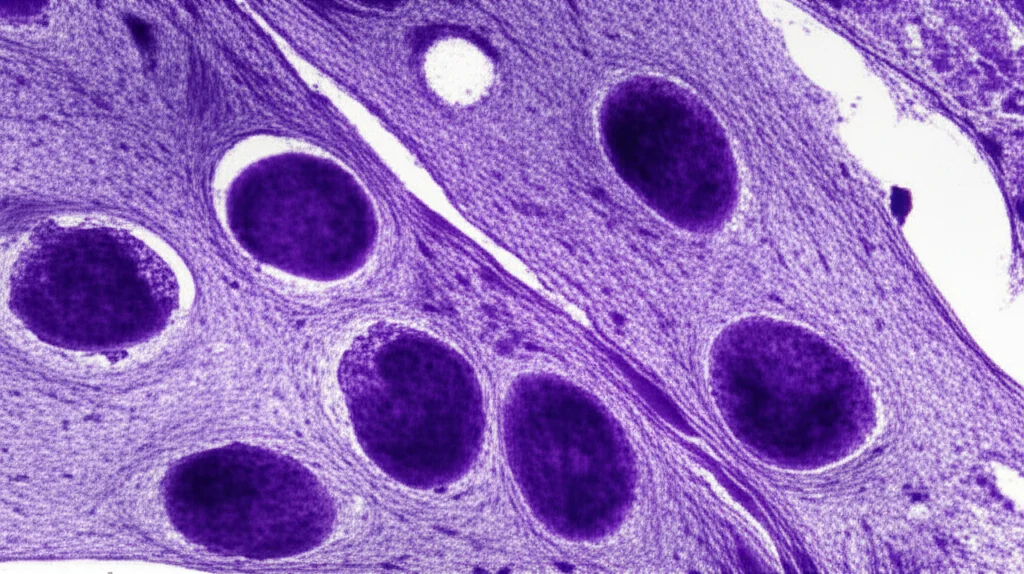

So, we dug in. We looked at these GCMN cells really closely. What we found was fascinating. While these nevi are caused by gene mutations (like in the RAS or RAF pathways) that *should* make cells grow like crazy, most of the cells in a mature GCMN weren’t actually dividing much. Instead, they seemed to be in a state called senescence. Think of it like they’ve hit the brakes on growing, but they just refuse to leave the party! This “growth arrest” is often a protective mechanism, but these cells stick around, causing the nevus to persist.

Current treatments that target the growth pathways, like MEK inhibitors, help with some symptoms, but they don’t eliminate the nevus cells. This told us that just stopping growth wasn’t enough. We needed a way to get rid of these stubborn cells entirely.

Finding the Survival Switch: BCL2

We asked ourselves: if these cells aren’t actively dividing but aren’t dying off either, how are they surviving for decades? We looked at the genes involved in cell survival and programmed cell death (apoptosis). And bingo! We found it. A protein called BCL2 was highly expressed in almost all the GCMN cells we looked at, whether they were the few still trying to divide or the vast majority stuck in that senescent state. It turns out, BCL2 is a major anti-apoptotic protein – it basically tells cells, “Nope, you’re not dying today!” This co-expression of the growth-arrest marker P16 and the survival protein BCL2 was a key clue. It pointed to a phenotype of “growth arrest and anti-apoptosis,” which is exactly what we saw clinically: nevi that don’t grow much but never go away.

Turning Off the Switch: Anti-BCL2 Therapy

This discovery got us really excited. If BCL2 is the survival switch, maybe we could use something to turn it off? Enter BCL2 inhibitors (BCL2i). These are drugs designed specifically to block the action of BCL2. We tested several of them on GCMN cells from patients in the lab. And wow, they worked! One in particular, called Venetoclax, was incredibly effective at killing the GCMN cells, much more so than the MEK inhibitors that only target growth.

We saw the cells undergoing apoptosis (programmed cell death), and we even saw increased levels of reactive oxygen species (ROS), which can also trigger cell death. Importantly, Venetoclax was much less toxic to normal skin cells like fibroblasts and keratinocytes, suggesting it could be quite specific to the nevus cells. It even knocked down some of the “stemness” traits in the GCMN cells, which is crucial for preventing recurrence.

But the real test is always in a living system. We used special mouse models that mimic human GCMN, including models with the common NRAS and BRAF mutations. We injected Venetoclax directly into the nevi or even gave it orally. The results were dramatic! The nevi shrank significantly, the pigmentation faded, and in many cases, the dark hair growing from the nevus turned gray or white (called leukotrichia), which is often seen in rare cases of spontaneous GCMN regression in humans. Histology confirmed that the nevus cells were being cleared out. And here’s the best part: in long-term follow-up, we saw no recurrence in the treated areas!

The Immune System Joins the Fight

Now, here’s where it gets even more interesting. The amount of Venetoclax we used in the mice, especially via injection, wasn’t quite high enough to kill *all* the cells based on our lab tests alone. This hinted that something else was helping. When we looked at the treated nevus tissue under the microscope, we saw a massive infiltration of immune cells. The immune system was clearly getting involved!

We used advanced single-cell sequencing to figure out which immune cells were there and what they were doing. Turns out, neutrophils, a type of white blood cell often associated with fighting infections, were the main players recruited to the treated nevi. And they weren’t just hanging around; they were active! They were expressing markers of activation and pathways related to inflammation and something called NETosis.

NETosis is a fascinating process where neutrophils basically throw out a web of DNA and proteins (called Neutrophil Extracellular Traps, or NETs) to trap and kill pathogens or damaged cells. Our data suggested these neutrophils were using NETs to help clear the nevus cells. We also found a key signaling molecule, IL1β, was highly expressed by the neutrophils, and it seemed to be communicating with the stressed nevus cells, potentially triggering both nevus cell death and neutrophil activation.

To prove how important the immune system, specifically neutrophils, was, we did experiments where we selectively depleted different types of immune cells in the mice before treatment. When we depleted neutrophils, the efficacy of the Venetoclax treatment dropped significantly. Inhibiting the IL1β signal also reduced the treatment’s effectiveness, though to a lesser extent than full neutrophil depletion. This strongly suggests that the anti-BCL2 therapy works in a dual way: it directly induces apoptosis in the nevus cells, and it also calls in the immune system, particularly neutrophils, to help clean up and finish the job via NETosis.

Hope for the Future

This is incredibly promising. We’ve found a therapy that targets both the senescent, persistent cells and the few proliferative cells in GCMN by hitting the BCL2 survival switch. And it seems to harness the body’s own immune system to enhance the clearance and prevent recurrence. The fact that we saw resident neutrophils and T cells in the treated areas long after the nevus was gone suggests a potential for long-lasting immune surveillance, which could be key to preventing the nevus from coming back.

While there are still steps to take – we need to understand exactly how BCL2 inhibitors trigger NETosis and test this approach in GCMN-associated melanoma – these findings lay a strong foundation for future clinical trials. We believe that BCL2 inhibitors like Venetoclax could offer a much-needed effective treatment option for individuals living with GCMN, potentially clearing these lesions more completely and safely than current methods.

It’s exciting to think that by understanding the unique survival mechanisms of these nevus cells and how they interact with the immune system, we might finally have a way to tackle this challenging condition head-on.

Source: Springer