Cracking the Pangenome Code: Meet AlfaPang, the Speedy Graph Builder!

Hey there, fellow explorers of the genomic universe! You know, for the longest time, when we wanted to understand the full picture of genetic variation within a group of organisms – not just one reference sequence, but *everyone’s* variations – we’ve turned to something called pangenome graphs. Think of it like building a super-map that includes all the different roads and paths found in a whole city, not just the main highway. These maps are super useful for spotting variations, understanding evolution, and even improving how we analyze experimental data.

Recently, the Human Pangenome Reference Consortium even put out a first draft of a human pangenome map built from 47 high-quality genomes, and it really helped reduce errors in finding variations. They’re planning to add way more genomes, aiming for 350! But here’s the catch: making these maps, especially from huge collections of genomes, is a *massive* computational headache. It takes serious time and memory.

The Old Ways and Their Headaches

Traditionally, building these pangenome graphs often involved aligning genomes to each other or to a reference. Imagine trying to line up hundreds or thousands of incredibly long, slightly different books page by page! Tools like the early versions of VG or Minigraph-Cactus did this, but the outcome could depend on the order you processed the genomes or which one you picked as the “reference” book. That feels a bit arbitrary, right?

Other approaches, like seqwish, tried aligning *all* pairs of genomes, but that doesn’t really scale well when you have tons of genomes. The pggb pipeline is a more recent attempt, chaining together alignment, graph inference, and refinement steps. These “variation graphs” are cool because they give you a sort of common coordinate system for all the sequences.

Then you have de Bruijn graphs, which are built differently, based on short overlapping sequences called k-mers. These don’t suffer from the order or reference bias, and tools like TwoPaCo or bifrost can build them super fast. But, they can be a bit tricky for downstream analysis, like figuring out where a specific gene is on the map.

So, we’ve had these two main types of maps, each with pros and cons. There’s been talk of bridging the gap, maybe with something called a string graph that generalizes both. The idea is to find a way to build the useful kind of variation graph structure efficiently.

Enter AlfaPang: An Alignment-Free Hero

This is where the really exciting stuff comes in! I’ve been looking at this new algorithm called AlfaPang. What’s neat about it? It’s *alignment-free*. Instead of lining everything up laboriously, it takes a different route. It builds the variation graph directly from the input sequences.

The core idea behind AlfaPang is based on some mathematical properties called k-completeness and k-faithfulness. Don’t let the fancy names scare you! Basically, k-completeness means that if the same k-mer (that short sequence snippet) appears in different places across your genomes, those places should be represented by the same path on the graph. k-faithfulness means you *only* merge things when it’s necessary to satisfy k-completeness – you don’t merge things just because they look a bit alike unless they share those specific k-mer connections. It turns out these properties uniquely define the graph structure!

AlfaPang essentially builds this graph by starting with a “generic” representation where every position in every sequence is its own node, and then it merges nodes based on these k-mer connections, creating what’s called a “quotient graph.” It does this for both simple directed graphs and more complex bidirected graphs that handle the double-stranded nature of DNA and inversions.

How Does It Actually Work (Conceptually)?

Imagine all your sequences strung together. AlfaPang finds all the occurrences of every unique k-mer. Then, it uses a clever way to group positions in the original sequences that should be merged in the final graph because they are part of the same k-mer occurrences. It uses data structures like a concatenated string of sequences, a list mapping positions to k-mer IDs, and an inverted index to quickly find where k-mers occur. It avoids building a massive, explicit graph by traversing these data structures implicitly, finding equivalence classes of positions that get merged into single nodes in the final graph. After building this initial graph (which is “singular,” meaning each node is just one character), it compresses unbranched paths into single nodes to make the graph more compact.

Putting AlfaPang to the Test: Performance

Okay, so the concept sounds cool, but how does it perform in the real world? This is where AlfaPang really shines. The analysis shows its time complexity is O(kN) and its space complexity is O(N), where N is the total size of the sequences and k is the k-mer size. What does that mean? It scales *linearly* with the amount of data. That’s a big deal!

They tested AlfaPang against parts of the pggb pipeline (wfmash+seqwish) and the full pipelines (AlfaPang+, pggb, Minigraph-Cactus) on datasets of *E. coli* and *Saccharomyces cerevisiae* genomes.

* Against wfmash+seqwish (the alignment heavy lifting): AlfaPang was significantly faster and used way less memory, especially as the datasets got larger. On 100 *E. coli* sequences, AlfaPang was over 20 times faster and used 5 times less memory, using only *one* thread compared to wfmash+seqwish’s 20 threads! It scaled much better.

* Against full pipelines (AlfaPang+ vs pggb vs Minigraph-Cactus): AlfaPang+ (AlfaPang followed by refinement steps) was generally the most efficient for *E. coli*, being faster and using 4-5 times less memory than the others on the largest dataset tested. For *S. cerevisiae*, Minigraph-Cactus was often the fastest overall, but AlfaPang+ showed better memory scalability and became faster than pggb on the largest dataset. Minigraph-Cactus achieves its speed partly by making different choices about what to align (it doesn’t align paralogs or sequences on different chromosomes), which affects the resulting graph.

It seems clear that for handling *really* large collections of genomes, AlfaPang’s efficiency, particularly its memory usage, gives it a significant edge.

What Kind of Maps Does It Build?

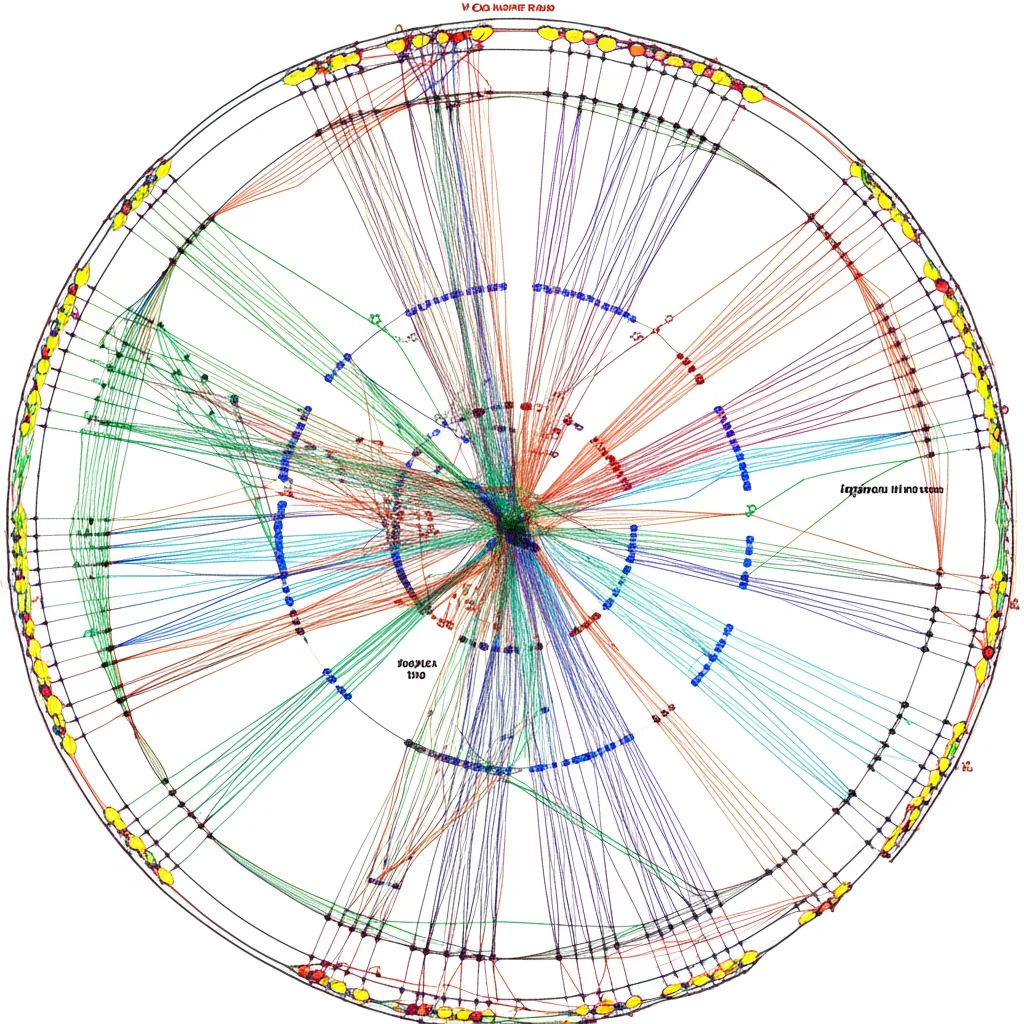

They also looked at the properties of the graphs built by the different tools – things like the number of nodes and edges, and how well they compressed the original sequences. AlfaPang+ and pggb produced graphs with similar numbers of nodes and edges, while Minigraph-Cactus graphs were noticeably larger. AlfaPang+ generally showed a higher rate of compression than pggb, which in turn compressed better than Minigraph-Cactus.

They also compared the “similarity” of the graphs by looking at which pairs of positions in the original sequences ended up being aligned (represented by the same vertex) in the graphs. AlfaPang+ tended to find more aligned pairs than pggb, suggesting it’s more sensitive to finding similarities. Minigraph-Cactus found fewer pairs overall, likely due to its design choices (like not aligning paralogs).

Finally, they checked if these aligned pairs were located in functionally important regions like genes. All tools showed similar distributions of aligned pairs across genes and intergenic regions, although AlfaPang+ sometimes found a higher proportion of pairs connecting genes to intergenic regions or within intergenic regions, especially in the larger *E. coli* datasets. This might again reflect its higher sensitivity to sequence similarity.

The Takeaway

So, what’s the big picture? AlfaPang is a new, alignment-free algorithm for building pangenome graphs. Its structure is mathematically defined by those k-completeness and k-faithfulness properties, which is pretty cool. But the real game-changer seems to be its efficiency. It scales linearly with the data size in terms of time and memory, which is a huge advantage over some state-of-the-art methods, especially for the massive genome collections being generated today.

Replacing the initial steps of the pggb pipeline with AlfaPang (creating AlfaPang+) results in graphs with similar overall structure but potentially higher sensitivity to sequence similarity, finding more aligned positions. While Minigraph-Cactus can be faster in some cases, its design means it misses certain types of alignments (like paralogs or inter-chromosome homologies) that AlfaPang+ might capture.

One thing to note is that while AlfaPang is fast, the refinement step (using smoothxg in the AlfaPang+ pipeline) currently takes up most of the total computation time. Improving or integrating this step could make the whole process even faster.

Ultimately, with population sequencing projects churning out thousands of genomes, memory efficiency is becoming absolutely critical. AlfaPang’s ability to handle huge datasets with much less memory could really open doors for new discoveries that were previously computationally impossible. It offers a powerful new tool in our bioinformatics toolbox for mapping the incredible diversity of life!

Source: Springer