Meet YingLong: Your Hyper-Local AI Weather Guru

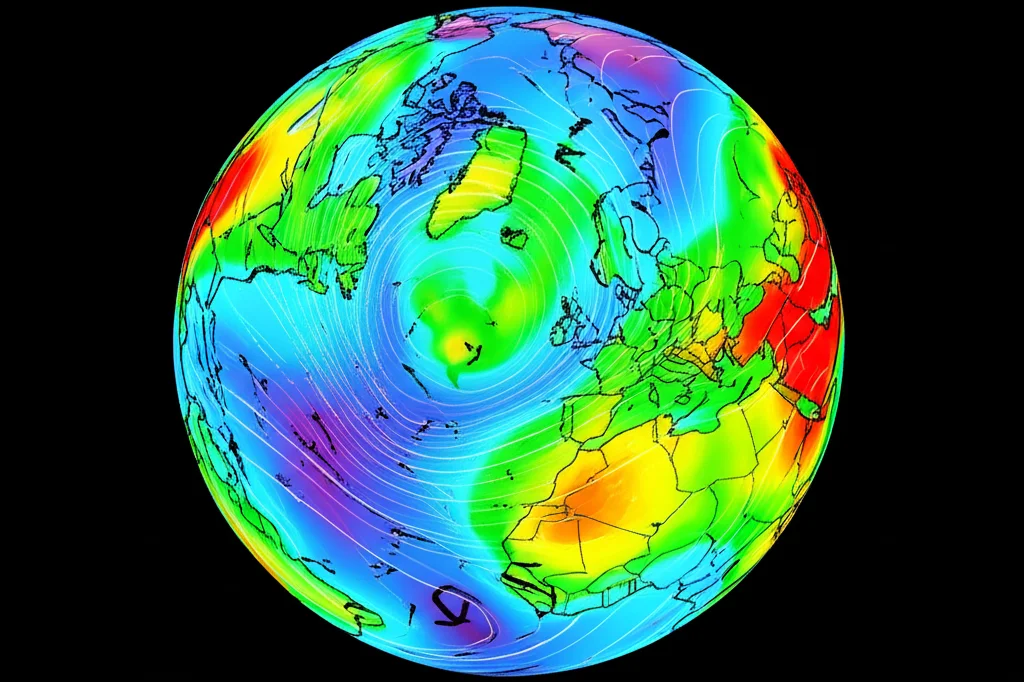

Hey there! Ever wonder why getting a super-accurate weather forecast for *just* your neighborhood feels like a bit of a dark art? We’ve got these amazing global weather models powered by AI now, which is seriously cool. They can predict weather across the whole planet way faster than the old-school methods. But when you zoom in, like, really zoom in on a specific area – think a city, a county, or even just a few countries – things get tricky.

Traditional weather forecasting for these smaller spots uses something called Limited Area Models (LAMs). They crunch complex physics equations, which is powerful but also, well, slow and needs a ton of computing power. While global AI weather models have been making waves, bringing that same AI magic down to the high-resolution, limited-area level has been a bit less explored. Until now, that is!

Enter YingLong: Our AI Local Weather Champ

So, we’ve been working on something pretty neat: an AI-based limited area weather forecasting model we call YingLong. Our goal? To bring the speed and efficiency of AI to those crucial high-resolution local forecasts. We’re talking a sharp 3 km spatial resolution and hourly updates – that’s pretty detailed!

YingLong is designed with a clever parallel structure, combining ‘global’ and ‘local’ branches. This helps it grab both the big picture weather patterns and the tiny, local details that make a difference in your backyard. We trained this model on some seriously detailed regional data (specifically, HRRR analysis data at 3 km resolution). And here’s a cool part: for its boundary conditions – basically, what’s happening just outside the area it’s focusing on – it uses forecasts from those speedy global AI models. This makes it way faster than the traditional physics-based LAMs.

Putting YingLong to the Test

We decided to see how YingLong stacked up against the traditional dynamical forecast models in two specific areas in North America: one relatively flat (we called it the East Domain, or ED) and one with some serious mountains (the West Domain, or WD). We focused on surface meteorological variables – the stuff that really impacts our daily lives:

- Surface temperature (T2M)

- Surface pressure (MSLP)

- Surface wind speed (U10, V10 – the components)

- Surface specific humidity (though this wasn’t directly predicted by YingLong in this study, it’s a key surface variable)

We compared YingLong’s forecasts (specifically, YingLong using Pangu-weather for its boundary conditions, or YingLong-Pangu) against the HRRR dynamical model forecasts (HRRR.F) using real-world observations as our benchmark. We looked at metrics like Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE – lower is better, meaning less error) and Anomaly Correlation Coefficient (ACC – higher is better, meaning the forecast matches the actual pattern better).

The Results: Wind Wins, Temp/Pressure Need a Little Help (For Now!)

So, what did we find? Well, for surface wind speed (U10 and V10), YingLong-Pangu generally had smaller RMSEs than HRRR.F. That means it was often more accurate at predicting the wind! This is pretty exciting, especially considering how important accurate wind forecasts are for things like wind power generation.

However, for surface temperature (T2M) and pressure (MSLP), YingLong-Pangu didn’t quite beat the dynamical model. In the flat ED, YingLong-Pangu and HRRR.F were comparable for temperature, but in the mountainous WD and for pressure in both areas, HRRR.F was generally more accurate. This difference is interesting – wind is a hydrodynamic variable (related to fluid motion and pressure gradients), while temperature and pressure are more thermodynamic and sensitive to local surface features like how the ground absorbs and releases heat.

We think the reason YingLong is better at wind might be because it was trained on analysis data that already incorporated observations, potentially correcting some errors from the dynamical model that generated that initial analysis. Temperature and pressure, on the other hand, are heavily influenced by surface radiative forcing, which wasn’t a direct input for YingLong’s training, but *is* a forcing variable for the dynamical model.

Improving the Forecast: The Boundary Condition Puzzle

One of the big takeaways is how crucial those lateral boundary conditions (LBCs) are. Remember, this is the information from outside the model’s focus area that influences what happens inside. We tested what happened when we used a ‘better’ LBC – specifically, using HRRR.F results at a coarser 24 km resolution as the boundary input for YingLong (YingLong-HRRR.F24), which provides more consistent information than the global Pangu-weather forecast.

Guess what? YingLong-HRRR.F24 performed significantly better for temperature and pressure, becoming comparable to or even *outperforming* HRRR.F in some cases for T2M! This strongly suggests that providing YingLong with better, more consistent information about what’s happening at its edges can really boost its performance on those trickier variables.

We also dug into the nitty-gritty of LBCs. We looked at different strategies for blending the coarse boundary information with YingLong’s fine-resolution forecast near the edges (a ‘smooth’ boundary condition vs. a ‘coarse’ direct replacement). The ‘smooth’ approach definitely helped, especially close to the inner area boundary, making the transition more seamless and improving forecasts.

We even experimented with how wide that lateral boundary region should be. We found that a width of around 207 km seemed to work best – wide enough to capture necessary information from outside influencing the inner area within an hour, but not so wide that it wastes resources or brings in irrelevant data.

Under the Hood: YingLong’s Architecture

Just quickly on how YingLong is built – it’s pretty cool! It uses an embedding layer to process the input data (all those weather variables and elevation). Then comes the spatial mixing layer, which is the heart of the parallel approach. It splits the data flow: one part goes through a ‘Local branch’ using something similar to the Swin Transformer architecture (great for capturing nearby relationships), and the other part goes through a ‘Global branch’ using an Adaptive Fourier Neural Operator (AFNO), which is good at seeing the bigger picture patterns across the whole area. These two branches work in parallel, and their results are combined before a linear decoder spits out the final forecast.

We did a bunch of tests (called ablation experiments) to figure out the best way to split the data between the local and global branches. We found that giving about 25% to the Local branch and 75% to the Global branch worked best for YingLong’s overall performance. This parallel design seems to be key to capturing those multi-scale weather features effectively.

Training and Data Quirks

We trained YingLong on a massive dataset – 7 years of hourly HRRR analysis data. This data actually came from different versions of the HRRR system over the years, which had some differences. We tested if this ‘version inhomogeneity’ messed things up, but it turns out having a *lot* of data (7 years!) was more important than having perfectly uniform data from just one version. Good to know!

Training took about 7 days on two powerful GPUs. But once trained, YingLong is super fast – it can generate a full 48-hour hourly forecast in about half a second on a single GPU. That’s way faster than running a traditional dynamical model for the same forecast!

Forecasting the Extremes

We also looked at how well YingLong predicts extreme wind events, like gales. We used metrics like Probability of Detection (POD – did it catch the extreme event?), False Alarm Ratio (FAR – did it predict an extreme event that didn’t happen?), and Symmetric Extremal Dependence Index (SEDI – a combined score). YingLong generally had lower POD and FAR than HRRR.F, meaning it missed some extreme events but also had fewer false alarms. However, its SEDI score was generally higher, suggesting it has a better overall balance in predicting extreme winds.

Real-World Impact: Powering the Future

Accurately forecasting wind speed, especially at high resolution and hourly intervals, is incredibly important for the wind power industry – for planning, operating, and maintaining wind farms. Since YingLong can forecast surface wind speed faster and often more accurately than traditional methods, it has serious potential to be a valuable tool for optimizing wind energy generation.

Wrapping Up

So, there you have it. We’ve built and tested YingLong, an AI-based model tackling the challenge of high-resolution weather forecasting for specific areas. It’s shown some real muscle, particularly in forecasting wind speed, and while it needs better boundary information to match dynamical models for temperature and pressure, the potential for improvement is clear. Its speed and efficiency compared to traditional methods are big wins. This is just the beginning, but I’m pretty excited about what AI can do for getting us those crucial, hyper-local weather details!

Source: Springer