Molecular Tug-of-War: How Proteins Compete to Build Your Cell’s Skeleton

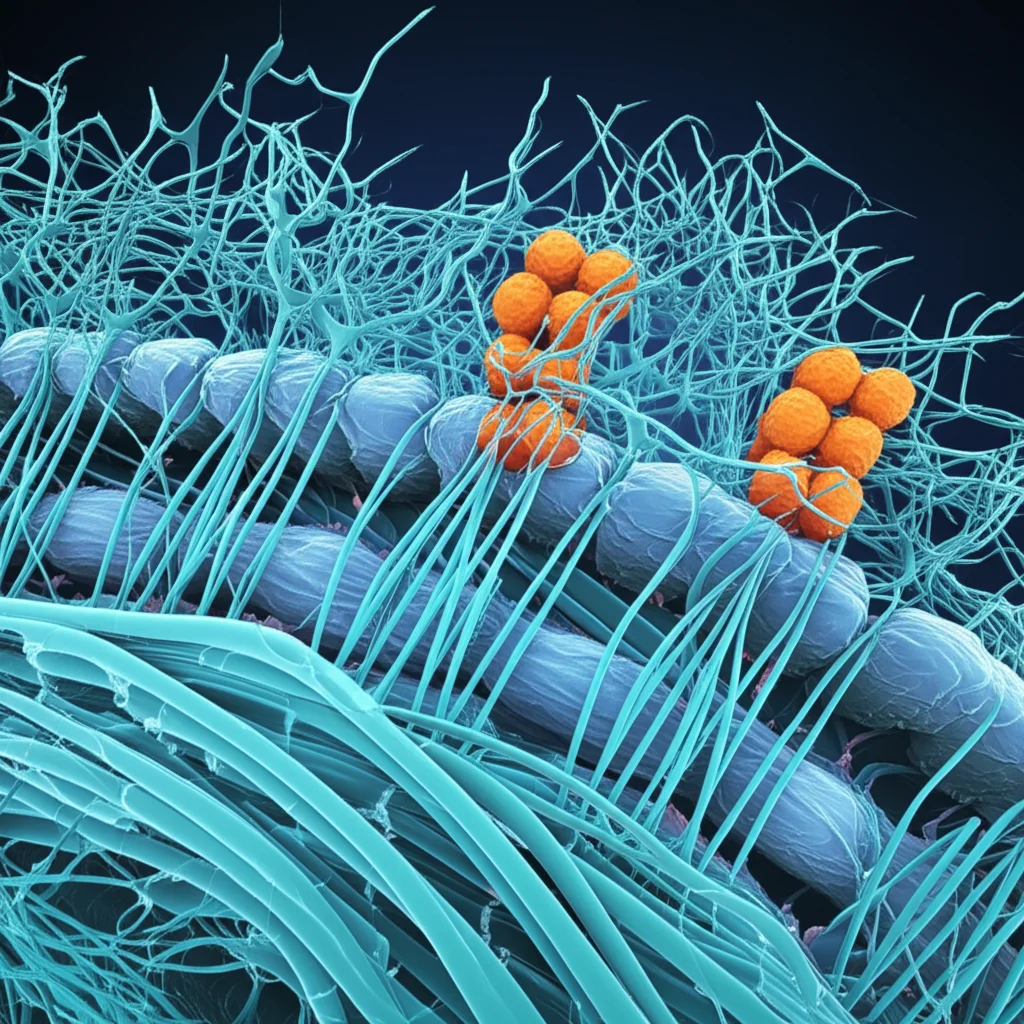

Hey there! So, I’ve been diving into the fascinating world inside our cells, specifically how they build and manage their internal scaffolding, the *actin* cytoskeleton. It’s like the cell’s structural engineer, constantly assembling and disassembling tiny protein threads (*actin* filaments) to move, divide, and grab stuff from outside. Pretty cool, right? But how does the cell decide *exactly* when and where to start building these threads? That’s a big question, and this research I’ve been looking at sheds some serious light on it, focusing on a key protein called *Las17* (or WASP in other organisms) in yeast.

The Cell’s Construction Crew Leader: Las17/WASP

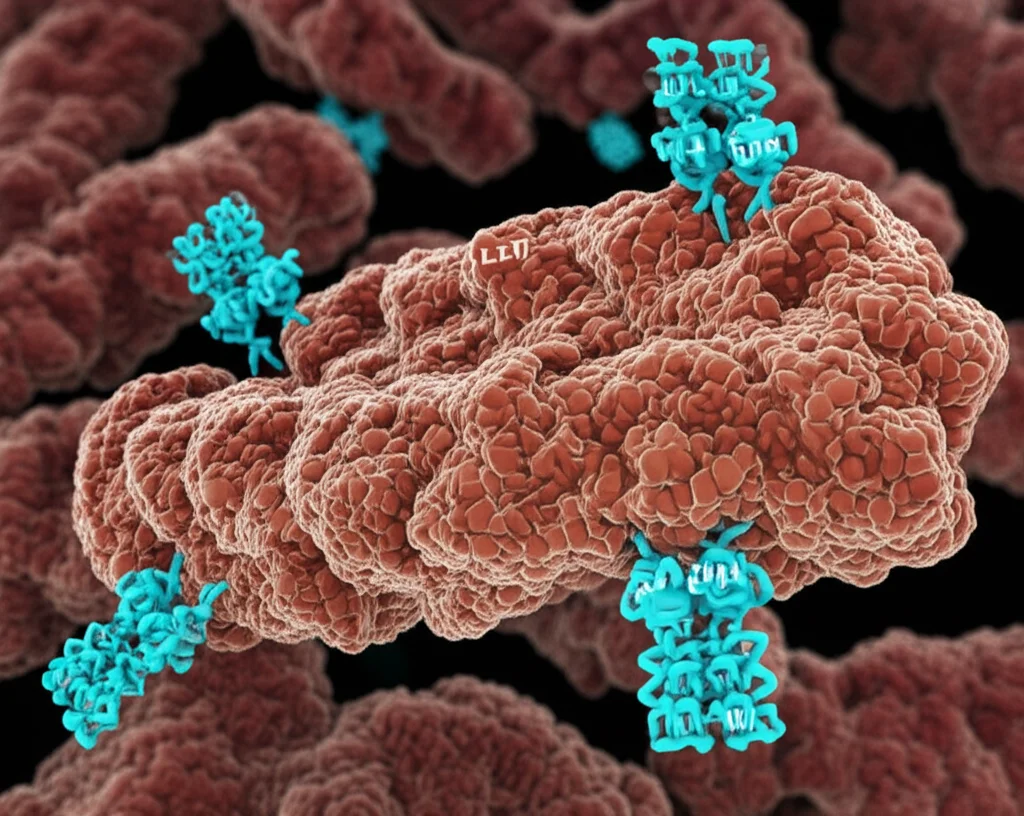

Think of *Las17* as a foreman on the construction site. Its main job is to kickstart the building of *actin* filaments, a process called nucleation. In yeast, this is super important for something called endocytosis, where the cell membrane pinches inward to swallow things. *Las17* has a special region at its tail end, the VCA domain, that’s known to activate a complex called *Arp2/3*, which then helps build branched *actin* networks. But there’s another part of *Las17*, the polyproline region (PPR), closer to its head, that scientists suspected was also doing something crucial, maybe even initiating the very first threads that *Arp2/3* then branches off of.

The Annoying Inhibitor: Sla1

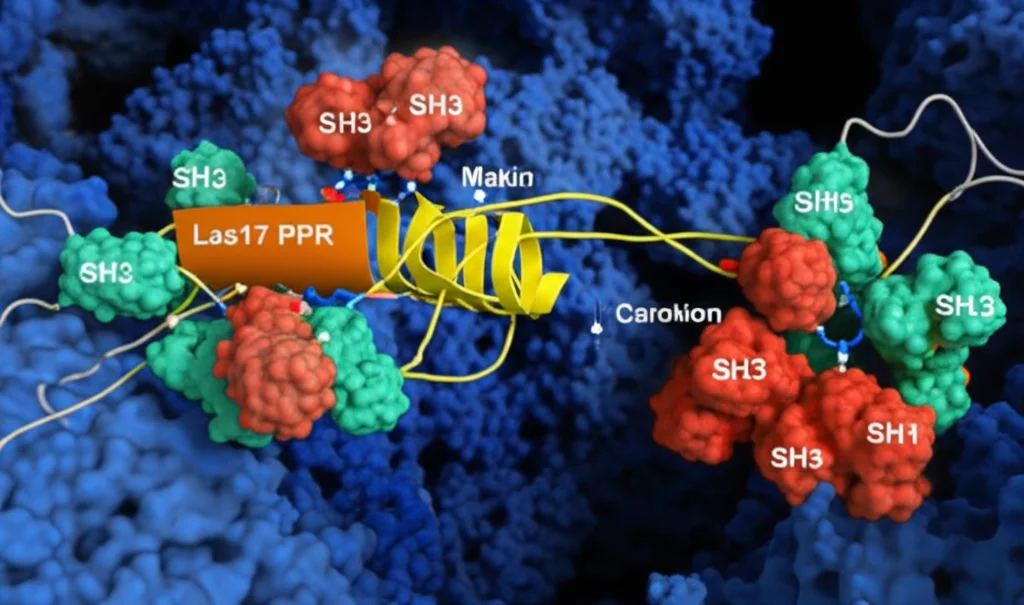

Now, every good construction site needs regulation, and *Las17* has a built-in inhibitor, a protein called *Sla1*. *Sla1* has these little grabby hands called SH3 domains. It turns out *Sla1* uses these SH3 domains to bind to the PPR of *Las17*, effectively putting the brakes on *Las17*’s activity. But here’s the puzzle: the SH3 binding happens way up at the head of *Las17*, while the *Arp2/3*-activating VCA domain is all the way down at the tail. How does binding so far away shut down the action? That’s one of the mysteries this study tackles.

Teamwork Makes the Inhibition Stronger

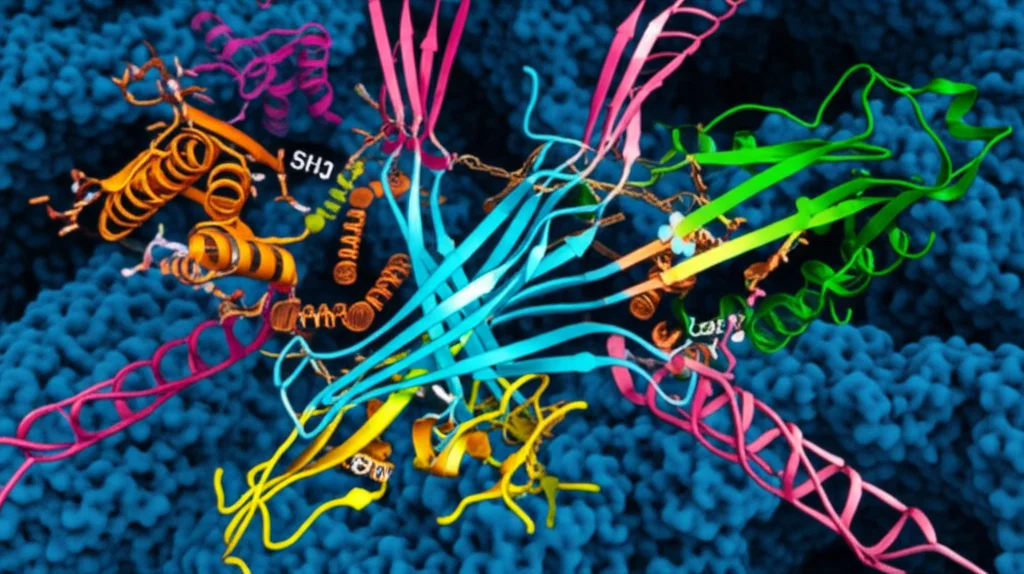

First off, I learned something really interesting about how *Sla1*’s SH3 domains bind. *Sla1* has three of these SH3 domains lined up. What the researchers found is that while a single SH3 domain from *Sla1* binds to *Las17*’s PPR, it’s not a super strong interaction. But when two or three of these SH3 domains are linked together, like they are in *Sla1*, their binding affinity for *Las17* jumps by over 100 times! It’s like one handshake is weak, but two or three linked hands create a much stronger grip. This “avidity” from having multiple binding sites close together is key to *Sla1*’s ability to really clamp down on *Las17*. They even used fancy techniques like Biolayer Interferometry (BLI) and NMR to measure this and look at the structure, confirming that the first two SH3 domains of *Sla1* act like a single, rigid unit.

Actin Wants In On the PPR Too!

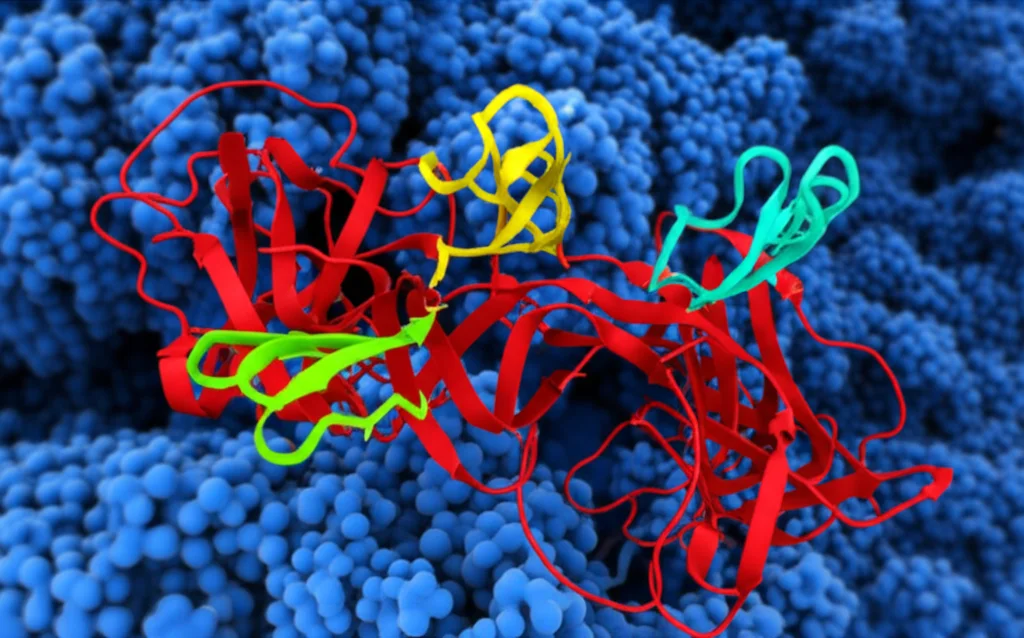

Okay, so *Sla1*’s SH3 domains bind tightly to the PPR. But what about *actin* itself? Remember, *actin* monomers are the building blocks. Previous work hinted that *actin* monomers might also bind to the PPR, not just the VCA domain. This study confirmed it! They found that the *Las17* PPR actually has *three* distinct sites where *actin* monomers can bind. Using structural modeling, they predicted how these *actin* monomers might snuggle up to the PPR. It looks like the binding involves specific arginine residues in *Las17* interacting with acidic residues on the *actin* monomer, particularly at the “barbed end” groove – that’s the part of *actin* that gets added to growing filaments.

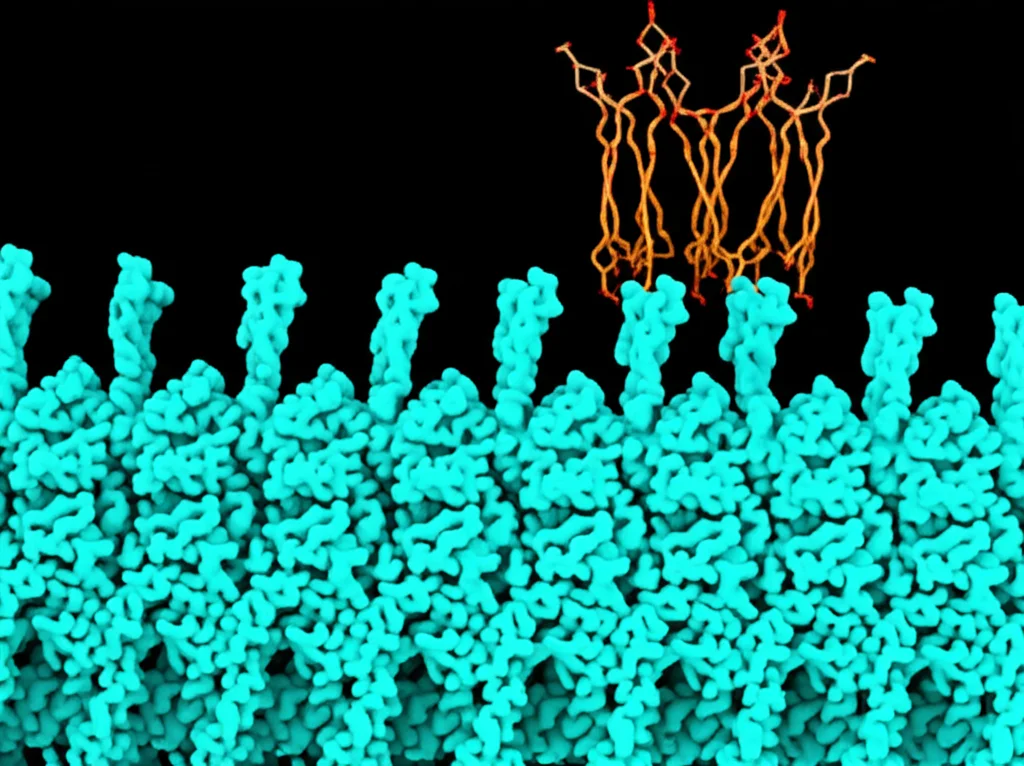

What’s even cooler is that the spacing of these three *actin* binding sites on *Las17* is just right for potentially lining up *three* *actin* monomers in a row. This kind of arrangement is similar to how other proteins, known as “longitudinal nucleators,” help start *actin* filaments. So, it seems *Las17*’s PPR isn’t just a passive binding site; it might actively help gather the first few *actin* monomers needed to start a new thread, even *before* *Arp2/3* gets involved. They used TIRF microscopy to watch filaments grow and saw that *Las17* alone could indeed increase the rate of filament formation, producing long, unbranched filaments, different from the branched ones *Arp2/3* makes.

The Molecular Tug-of-War: Competition is Key

Here’s where the plot thickens and the mystery of *Sla1*’s inhibition gets clearer. Since both *Sla1*’s SH3 domains and *actin* monomers bind to the *same* PPR region of *Las17*, could they be *competing* for those spots? The researchers put this to the test using Microscale Thermophoresis (MST). They measured how well *actin* bound to *Las17*’s PPR, and then they added *Sla1*’s linked SH3 domains. Bingo! Adding *Sla1* SH3 domains dramatically reduced *actin*’s binding affinity for *Las17* – by about 40-fold!

This is a game-changer. It suggests that *Sla1* inhibits *Las17* not just by some distant signal, but by physically blocking the very sites on the PPR where *actin* monomers need to bind to start a filament. It’s a direct competition for real estate on the *Las17* protein. When *Sla1* is bound, *actin* can’t get a foothold, and polymerisation is shut down.

How to Release the Brakes? Enter Sec4 and Friends

If *Sla1* is the brake, how does the cell release it at the right time and place? The researchers looked for factors that might interfere with *Sla1*’s tight grip on *Las17*. Previous work showed a small protein called *Sec4*, a GTPase, could alleviate *Sla1* inhibition during endocytosis. This study confirmed that activated *Sec4* could indeed rescue *Las17*-mediated *actin* polymerisation from *Sla1* inhibition, even the *Arp2/3*-independent kind.

Using structural prediction tools like Alphafold, they modeled how *Sec4* might interact with *Las17*. The model suggests *Sec4* binds to a region of *Las17* that overlaps with one of the PPR’s polyproline motifs (PP1), right near one of the newly identified *actin* binding sites (ABS1). This binding could potentially weaken *Sla1*’s hold on that particular spot, tipping the competitive balance just enough to let *actin* start binding.

But it’s likely not just *Sec4*. The researchers also found evidence that *Sla1* itself might bind to membranes via a newly identified lipid-binding region (a putative PH domain). Other proteins involved in endocytosis, like *Sla2* and even ubiquitin (a tag on cargo), are known to bind to different parts of *Sla1*.

The “Unzipping” Model

Putting it all together, the picture that emerges is one of a complex, dynamic switch. When *Sla1* and *Las17* first arrive at the endocytosis site, *Sla1*’s multiple SH3 domains are tightly bound to *Las17*’s PPR, keeping it inactive. But then, interactions with other factors at the membrane – like *Sec4* binding to *Las17*, *Sla1* binding to membranes, *Sla1* binding to *Sla2*, or *Sla1* binding to ubiquitinated cargo – start to weaken *Sla1*’s grip. It’s like *Sla1* gets “unzipped” from *Las17*’s PPR, one SH3 domain at a time, as it zips into new interactions closer to the cargo and membrane.

Testing the Balance in Living Cells

To really prove this competitive binding idea is important in a living cell, the researchers made a clever mutation in *Las17*. Based on their binding studies, they changed a single proline residue (P387A) in the third polyproline motif (PP3) of *Las17*. This specific mutation significantly reduced the binding of *Sla1*’s SH3 domains *in vitro*, but crucially, it *didn’t* seem to affect *actin* monomer binding.

What happened when they put this mutated *Las17* back into yeast cells? The cells could still grow, but they were more sensitive to drugs that mess with *actin*. More importantly, when they watched the endocytosis process using fluorescent tags, things were *weird*. The mutant *Las17* stayed at the membrane for much longer, and the subsequent steps, like the recruitment of *Arp2/3* and the inward movement of the membrane, were delayed and often aberrant. Instead of smooth, regulated events, they saw patches retracting and general disorganization.

This cellular experiment is powerful because it shows that simply weakening the *Sla1* SH3 binding to *Las17* (while keeping *actin* binding intact) isn’t a shortcut to faster endocytosis. Instead, it disrupts the delicate balance, leading to unregulated and inefficient *actin* dynamics. This really underscores the importance of that competitive switch being tightly controlled.

The Bigger Picture: Fuzzy Interactions and Precise Control

What I took away from this is that the regulation of *actin* polymerisation by proteins like *Las17* is way more nuanced than just an on/off switch activated by the VCA domain. The head region, the PPR, is a critical player, capable of binding *actin* monomers itself and potentially initiating those first crucial threads. And its activity is controlled by a dynamic competition between *actin* and inhibitory SH3 domains.

This competition isn’t just about one strong interaction winning out. It’s about a network of *multiple, often weak* interactions (what some call “fuzzy” binding) involving *Sla1*, *Las17*, membranes, cargo, and other proteins like *Sec4* and *Sla2*. The combined strength and timing of these interactions determine whether *Sla1* stays zipped onto *Las17*, keeping it quiet, or whether it gets unzipped, allowing *actin* to bind the PPR and kickstart the construction process.

Understanding this kind of competitive, multi-factor regulation in yeast endocytosis gives us valuable insights into how similar WASP proteins work in our own cells for processes like cell movement, immune responses, and even how pathogens hijack our cells. It highlights that precise cellular events often rely on a symphony of many players, each with relatively weak interactions, coming together in just the right way at just the right time. It’s a beautiful, complex dance happening inside us all the time!

Source: Springer